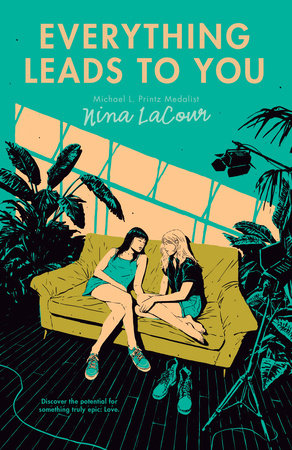

***This excerpt is from an advance uncorrected proof.***

Copyright © 2014 by Nina LaCour

Chapter One

Five texts are waiting for me when I get out of my English final. One is from Charlotte saying she finished early and decided to meet up with our boss, so she’ll see me at Toby’s house later. One is from Toby, saying, 7 p.m.: Don’t forget! And three are from Morgan.

I don’t read those yet.

I head off campus and a few blocks over to where I parked my car in an attempt to avoid the daily after-school gridlock. But of course the driver’s side lock won’t unlock when I turn the key, so I have to go around the passenger side and open the door and climb across the seat to pull up the other lock and shut the passenger door and go around to the driver’s side again—and by the time I’m through with that twenty-second process, the cars are already backed up at the light. So I inch into the road and pull out my phone and read what Morgan wrote.

You okay?

R u coming to set later?

I miss you.

I don’t write back. I am going straight to set, but not to see her. I need to measure the space between a piano and a bookshelf to see if the music stand I found on Abbot Kinney Boulevard yesterday will make things look too crowded. The music stand is beautiful. So beautiful, in fact, that if it doesn’t fit I will find a new bookshelf, or rearrange the furniture entirely, because this is exactly what I would have in my practice room if I knew how to play an instrument. And if I could afford a nine-hundred-dollar music stand.

As the light turns and I roll my car through the intersection, I’m trying to ignore Morgan’s texts and think only of the music stand. This music stand is a miracle. It’s exactly what I didn’t even know I was looking for. The part that holds the sheet music is this perfect oxidized green. When I texted my boss a picture of the stand she wrote back, Fucking amazing!!!! An expletive and four exclamation marks. And when I texted Morgan to tell her that this was the last time I would allow myself to get dumped by her, that breaking up and getting back together six times was already insane, and there was absolutely no way I would take her back a seventh, she replied with, I don’t know what to do! Indecisive and only mildly emphatic. So typical.

But the music stand, the music stand.

Turning right onto La Cienega, my phone rings and it’s Charlotte.

“You need to come here,” she says.

“Where?”

“Ginger took me to an estate sale.”

“A good one?”

“You just have to come.”

“Someone famous?”

“Yes,” she says.

“Sounds fun but I need to measure for that music stand.”

“Emi,” she says. “Trust me. You need to come here now.”

So I scribble down the address, make a U-turn, and head toward the Hollywood Hills. I drive up Sunset and roll down all the windows, partly because the air-conditioning doesn’t work and it’s ninety degrees, but mostly because I’m driving past palm trees and hundreds of beauty parlors and taco trucks and doughnut shops and clothing stores and nightclubs, and I like to take it all in and think about how Los Angeles is the best place in the world.

I turn when my phone tells me to turn and start ascending the hills, where the roads become narrower and the houses more expensive. I keep going, higher than I’ve ever gone, until the houses are not only way bigger and nicer than the already big, nice houses below them, but also farther apart. And, finally, I turn into a driveway that I’m pretty sure has never before encountered a beat-up hatchback with locks that don’t work.

I park under the branches of old, gorgeous trees that are full and green in spite of the arrival of summer, step out of my car, lean against the bumper, and take a look at this house. My job has taken me to a lot of ridiculously nice houses, but this one stands out. It’s older and grander, but there’s more to it than that. It just feels different. More significant. I’m not thinking about Morgan and thinking instead about who might have owned this house. It was probably someone old, which is good, because an estate sale means someone has died, and it’s sad to dig through thirty-year-old people’s stuff and think about the futures they could have had.

The double front doors swing open and Charlotte steps into the sun. Her jeans are rolled up at the ankles and her blond hair is in pigtails, and her face is part serious, part elated.

“Guess,” she says.

I try to think of who has died in the last couple of weeks. My first thought is our physics teacher’s grandmother, but I seriously doubt she would have lived in a house like this one. Then I think of someone else, but I don’t say anything because the thought is crazy. This death is huge. Front-page huge. Every-time-I-turn-on-the-radio huge.

But then—there’s this house, which is clearly an important house, and old, beautiful trees, and Charlotte’s mouth, which is twitching under the tremendous effort of not smiling.

Plus it isn’t swarming with people, which means this is some kind of preview that Ginger got invited to because she’s a famous production designer and she always gets called to these things first.

“Holy shit,” I say.

And Charlotte starts nodding.

“You’re not serious.”

Her hands fly to her face because she’s giddy with the delirious laughter of someone who has spent the last hour in the house of a man who was arguably the most emblematic actor in American cinema.

Clyde Jones. Icon of the American Western.

She leans against the house, doubles over, slides onto the marble landing. I let her have one of her rare hysterical fits of laughter as I take it all in. I can’t think of enough expletives to perfectly capture this moment. I would need a year’s worth of exclamation points. So I just stare, openmouthed, thinking of the man who used to live here.

Charlotte’s hysterics die down, and soon she is standing, composed again, back to her super-brilliant, future museum-studies-major self.

“Come in,” she says.

I pause in the colossal doorway. Outside is bright and hot, a beautiful Los Angeles day. Inside it’s darker. I can feel the air-conditioning escaping. Even though this is an amazing opportunity that will never come again, I don’t know if I should go any farther. The thing is this: My brother, Toby, and I talk all the time about what movies do. They speak to our desires, which are never small. They allow us to escape and to dream and to gaze into eyes that are impossibly beautiful and huge. When you live in LA and work in the movies, you experience the collapse of some of that fantasy. You know that the eyes glow like that because of lights placed at a specific angle, and you see the actresses up close and, yes, they are beautiful, but they are human size and imperfect like the rest of us.

This, though, is different.

Because even if you know a little bit too much about how movies are made, there are always things you don’t know. You can hold on to the myth surrounding the actors; you can get swept up in the story.

Clyde Jones belongs in the Old West. He belongs under the stars, smoking hand-rolled cigarettes and listening to the wind. In A Long Time Till Tomorrow he lived in a log cabin. In Lowlands he lived out of a green pickup truck, sleeping by the side of the road a couple hours at a time, searching for a woman from his past.

Clyde Jones is the savior. The good, uncomplicated man. The perfect cowboy. But as soon as I walk through this doorway he will be an actor who spent his life in a Los Angeles mansion. The ultimate collapse of the fantasy.

“Em?” Charlotte says. She steps to the left, gesturing that I should follow, and I can’t help myself. A moment later I’m in Clyde Jones’s foyer, the doors shut behind me, gazing at one of the most beautiful objects I’ve ever beheld: a low-hanging chandelier, geometric and silver and shining.

Clyde Jones was no cowboy, but his aesthetic sensibilities were amazing.

I’m still dying over Clyde’s house when Ginger strides past me.

“Oh, good, Emi, you made it.” Charlotte and I follow her into the living room.

“Yeah,” I say, standing under the high white-beamed ceiling, next to what I can only assume is a pair of original Swan chairs positioned under a huge pastoral landscape with a clear sky as endless as the skies in his films. “It’s probably better that I don’t go to the studio today.”

“These glasses,” Ginger says, pointing, and Charlotte walks over to a shiny minibar and takes a tray of highball glasses. “Why should you avoid the studio? Oh, let me guess: Morgan.”

“She broke up with me.”

“Again?”

“Something about not being tied down. Life’s vast possibilities.”

“‘ Life’s vast possibilities.’ Such bullshit,” Charlotte says, setting the glasses next to a group of other beautiful objects that Ginger must have already chosen.

I say, “Yeah,” but only because that’s what Charlotte needs me to say. Charlotte is the kind of friend who automatically hates everyone who has ever done me wrong. The first time Morgan broke up with me and we got back together, Charlotte tried her best to get over it and be nice to Morgan. But somewhere around the third time, Charlotte got rude. Stopped saying hi. Stopped smiling around her. By now, Charlotte can’t even hear Morgan’s name without clenching her jaw.

Ginger shoots me a sympathetic look.

“It’s okay,” I tell her. “I’m done with movie people.”

And then we all laugh, because really. What a ridiculous thing to say.

~

When Ginger is finished choosing what she wants, she lets Charlotte and me explore for a while and see if there’s anything we want to buy. We find ourselves in Clyde’s study, which has to be the size of my brother’s entire apartment. It has high ceilings supported by thick wooden beams and an entire wall of windows with doors that slide open to the land in back. Of all the rooms, this one feels the most Western. There’s an enormous rustic table that he must have used as a desk and a collection of leather chairs arranged in a semicircle facing a cavernous fireplace. Shelves line the entirety of one of the side walls, and covering the shelves are hundreds of awards including four Oscars, along with objects from his films: cowboy hats and guns and silver belt buckles.

Most people our age don’t know or care very much about Clyde. His career is long over. His roles were rarely sophisticated or smart; there isn’t much to recommend him to my generation. But my brother has eclectic tastes, and when he loves something, it becomes nearly impossible not to love it along with him. So over the years I became infatuated with the moment that Clyde appears on the horizon or in the saloon or riding through tall grass toward the woman he loves.

Standing in his study now feels both unexpected and inevitable. And, more than those things, it feels meaningful. Like all of Clyde’s arrivals. Like, without knowing it, everything I’ve done has been building toward this moment.

”Are you all right?” Charlotte asks me.

I just nod, because how could I describe this feeling in a way that would make sense? There is no logic behind it.

I pick up one of the belt buckles. It’s heavier than I thought it would be, and more beautiful up close: the smooth silhouette of a bucking horse with a rough mountain and waning moon in the background.

“I’m going to see how much they’re asking for this,” I say.

Charlotte cocks her head. “You’re choosing a belt buckle?”

“It’s for Toby,” I say, and Charlotte blushes because she’s been in love with my brother forever. Reminded, I check my phone and see that we’re supposed to meet up with him in just under two hours.

Charlotte’s flipping through records. She pulls out a Patsy Cline album.

“I can’t get over this,” she says. “Clyde Jones used to sit on these chairs and listen to this record.”

We find Ginger signing a credit card slip for over twenty thousand dollars, which might explain why, when we show the estate sale man the belt buckle and Patsy Cline record, he beams at us and says, “My gift to you.”

“Charlotte, will you get Harrison on the phone?” Charlotte does, and hands the phone to the man to arrange a pickup, and then we are back in Clyde’s hot drive- way, out of his house forever.

~

Toby lives in a classic LA courtyard apartment, like the one in David Lynch’s film Mulholland Drive, which chooses to focus on the darker side of the movie business, and also the one in Melrose Place, which was a nineties TV show set in West Hollywood that my dad lectures about in his Pop Culture of Los Angeles course at UCLA. Toby’s courtyard has a tidy green lawn and a pretty fountain, and from the side of his cottage you can see a tiny strip of the ocean. We walk in, and there is his stuff, packed, waiting by the door. A set of matching suitcases that look so grown up.

He hugs us both. Me first and long, Charlotte next and quicker. Then he stands and faces us, my tan brother with his crooked smile and black hair that’s always in his eyes. I feel sad, and then I push the sadness away because of what we have to tell him.

“Toby,” I say. “We spent the afternoon in Clyde Jones’s house.”

“You’re shitting me,” he says, his eyes wide.

“No,” Charlotte says. “Not at all.”

“His house was full of the most amazing—” I start, but Toby puts his hands over his ears.

“Dont’tellmedon’ttellmedon’ttellme,” he says.

“Okay,” I say.

“The collapse of the fantasy,” he says.

I know, I mouth, all exaggerated so he can read my lips.

“I love Clyde Jones,” he says, dropping his hands.

I nod. “Not another word on the subject,” I say. “But I do have something for you. Close your eyes.”

My brother does as told and holds out his hands. I pretend I don’t notice Charlotte staring at him, and place the belt buckle in his cupped palms. He opens his eyes. Doesn’t say anything. I wonder whether I chose the wrong object, and then I realize that tears are starting.

“Oh, please,” I say.

“Holy. Shit.” He blinks rapidly to compose himself. Then he rushes to his bookshelf of DVDs and pulls one out. He’s mumbling to himself as he turns on his TV and waits for the chapter selection to appear on the screen. “Saloon door . . . I’m a man of the law but that don’t make me honest . . . Round these parts . . . Yes!”

He’s found the scene, and we all squeeze onto my parents’ old sofa, me in the middle acting as a buffer for the sexual tension between my brother and my best friend.

Toby presses play and turns up the volume. I recognize it as The Strangers, but I’ve only seen it a couple times so I’ve forgotten a lot of what’s happening. The scene begins with a shot of a saloon door. We hear the voices of the people inside but the camera doesn’t turn to them. When one person matters so much, all you can do is wait for his arrival. And then boots appear at the bottom of the door, a hat above it. The doors burst open and there stands Clyde Jones.

The screen fills with a close-up of his young, knowing face, shaded by a cowboy hat. He scans the saloon until he sees the sheriff, drinking at a table with one of the bad guys. The camera shifts to his cowboy boots as they stomp across the worn wooden floor toward the sheriff and his buddy, who both spring up from the table and draw their guns as soon as they see Clyde.

Unfazed, Clyde deadpans, “I thought you were a man of the law.”

Sheriff: “I’m a man of the law but that don’t make me honest.”

The bad cowboy doesn’t say anything, but looks borderline maniacal as he points the gun at Clyde.

Then Clyde says, “Round these parts, lawlessness is a disease. I have a funny suspicion I know how to cure it.”

The camera moves down to his holster, and Toby shouts, “Look!” and presses pause. There’s the belt buckle: the horse, that hill, the moon.

Charlotte says, “That’s amazing!”

I say, “Toby. I am seriously worried about you. Of all the Clyde Jones movies and all the belt buckles, how did you know that this buckle was in this scene of this movie?”

But Toby is doing a dance around his living room, ignoring me, reveling in the glory of his new possession.

“Thank you, thank you, thank you,” he chants.

After a while Toby calms down enough that we can watch the rest of the movie, which goes by quickly. Clyde kills all the bad guys. Gets the girl. The end.

“Okay,” Toby says. “I asked you both here for a reason. Come to the table.”

I’m trying to hold on to the good feeling of the last hour, but the truth is I’m getting sad again. Toby is about to leave for two months to scout around Europe for this film that starts shooting soon. It’s stupid of me—it’s only two months, and it’s a huge promotion for him—but Toby and I spend a lot of time together so it feels like a big deal. Plus he’s going to miss my graduation, which I shouldn’t care about because I’ve been over high school for a long time. But I do care just a little bit.

Toby opens the door to the patio off the kitchen and the night air floods in. He pours us some iced tea he gets from an Ethiopian place around the corner. The people there know him and sell it to him in a plastic pitcher that he takes back and gets refilled every couple days. They don’t do it for anyone else, only Toby.

When we’re seated at the round kitchen table, he says, “So, you know how I put up that ad to sublet my place? Well, I got all these responses. People were willing to spend mad cash to live here for two months.”

“Sure,” I say. Because it’s obvious. His place is small but super adorable. It’s this happy mix of Mom and Dad’s old worn-in furniture and castoffs from sets I’ve worked on and things we picked up from Beverly Hills yard sales, where rich people sell their expensive stuff for cheap. It’s just a few blocks from Abbot Kinney, and a few blocks more from the beach.

“Yeah,” he says. “So it was seeming like it was gonna work. But then I had a better idea.”

He takes a sip of his tea. Ice clinks. Charlotte leans forward in her chair. But me, I sit back. I know my brother, the master of good ideas, is waiting for the right moment to reveal his latest plan.

Finally, he says, “I’m letting you guys have it.”

“Whaaaat?” I say. Charlotte and I turn to each other, as if to confirm that we both just heard the same thing. We shake our heads in wonder. And then I can’t help it, I think of the third time Morgan broke up with me, when her reason was that I was younger (only three years!) and lived with my parents. Would it make a difference to her whether I lived here instead? Or is this time really about the vastness or whatever?

Charlotte says, “Are you serious?”

And Toby grins and says, “Completely. It’s my graduation present to both of you. But there’s a condition.”

“Of course,” I say, but he ignores me.

“I want you to do something with the place. Something epic. And I don’t mean throw a party. I mean, something great has to take place here while I’m gone.”

“Like what?” I ask. I’m a little worried, but excited, too. Toby’s the kind of person whose greatness makes other people want to rise to any occasion. Everything he does is somehow larger than life, which is how he worked his way from a summer job as one of the parking staff to a full-time job as the location manager’s assistant. And then, last month, at the age of twenty-two, he became the youngest location scout in the studio’s recent history.

“That’s all I’m gonna say on the subject,” he says. “The rest is up to you.”

We try asking more questions but when we do he just sits back and smiles. So the conversation shifts to The Agency, the film he’s scouting for. I get to design a room for it, too, which will be my biggest job yet. It’s a huge-budget movie with a young ensemble cast—Charlie Hayden and Emma Perez and Justin Stark—all the really big young actors. It’s a spy adventure, but the room I’m designing is for one of the girls when she’s still supposed to be in high school, before they all become spies and start traveling around the world. It’s probably going to be a stupid movie, but I’m thrilled about it anyway. A few weeks ago, Toby and I got to go to a party with the director and the whole cast and crew. I hung out with these stars whose faces are on posters all across the world. That’s just one example of the kinds of things I get to do because of Toby.

Too soon, a knock comes on Toby’s door—what is now for two months my door—and the film studio driver sweeps his suitcases into the trunk and then sweeps up my brother, too. Toby dangles the keys out the window, then looks out at me and says, “Epic.”

The car pulls away and we wave and then it turns a corner and is gone. And Charlotte and I are left on the curb outside the apartment.

I sit down on the still-warm concrete.

“Epic,” I say.

“We’ll think of something,” Charlotte says, sitting next to me.

We sit in silence for a while, listening to the neighbors. They talk and laugh, and soon some music starts. I’m trying to push away the heavy feeling that’s descending now, that has been so often lately, but I’m having trouble. A few months ago it seemed like high school was going to last forever, like our college planning was for a distant and indistinct future. I could hang out with Charlotte without feeling a good-bye looming, take for granted every spur-of-the-moment plan with my brother, sneak out at night to drive up to Laurel Canyon with Morgan and lie under blankets in the back of her truck without worrying that it would be the last time. But now the University of Michigan is taking my best friend from me in just over two months, and my brother is off to Europe tonight and who knows where else after that. Morgan is free to kiss any girl she wants. I expected graduation to feel like freedom, but instead I’m finding myself a little bit lost.

My phone buzzes. Why didn’t you come to work? I hide Morgan’s name on the screen and ignore Charlotte’s questioning look.

“Hey, we should listen to that record you got,” I say, and Charlotte says, “Nice way to avoid the question,” and I say, “Patsy Cline sounds like a perfect way to end the evening,” which is a total lie. I don’t know why Charlotte likes that kind of music.

But I fake enthusiasm as she takes the record out of its sleeve and places it on Toby’s record player and lowers the needle. We lie on Toby’s fluffy white rug (I got it from a pristine Beverly Hills yard sale for Toby’s twenty-first birthday, along with some etched cocktail glasses) and listen to Patsy sing her heart out. Each song lasts approximately one minute so we just listen as song after song plays. Truthfully? I actually like it. I mean, the heartbreak! Patsy knew what she was singing about, that’s for sure. It’s like she knows I have a phone in my pocket with texts from a girl who I wish more than anything really loved me. Patsy is telling me that she understands how hard it is not to text Morgan back. She might even be saying Dignity is overrated. You know what trumps dignity? Kissing.

And I might be sending silent promises to Patsy that go something like Next time Charlotte gets up to go to the bathroom I’ll just send a quick text. Just a short one.

“That was such a good song,” Charlotte says.

“Oh,” I say. “Yeah.”

But I kind of missed it because Patsy and I were otherwise engaged and I swear that song only lasted six seconds.

“I wonder who wrote it,” she says, standing and stretching and making her way to the album cover resting against a speaker.

This is probably my moment. She’ll look at the song list and get her answer and then she’ll head to the bathroom and I will write something really short like Let’s talk tomorrow or I still love you.

“Hank Cochran and Jimmy Key,” she says. “I love those lines ‘If still loving you means I’m weak, then I’m weak.’”

“Wow,” I say. It’s like Patsy is giving me permission to give in to how I feel. “Are the lyrics printed?” I ask, sitting up.

“Yeah, here.” Charlotte steps over and hands me the record sleeve, and as I take it something flutters out. I pick it up off the rug.

“An envelope.” I check to see if it’s sealed. It is. I turn it over and read the front. “‘ In the event of my death, hand-deliver to Caroline Maddox of 726 Ruby Avenue, Apartment F. Long Beach, California.’”

“What?” Charlotte says.

“Oh my God,” I say. “Do you think Clyde wrote that?”

We study the handwriting for a long time. It’s that old-guy handwriting, cursive and kind of shaky, but neat. Considering that 1) Clyde lived alone, and 2) this record belonged to Clyde, and 3) Clyde was an old man who probably had old-man handwriting, we decide that the answer to my question is Definitively Yes.

The feeling I had in Clyde’s study comes back. The envelope in my hand is important. This moment is important. I don’t know why, but I know that it’s true.

“We should go there now,” I say.

“To Long Beach? We should probably let the estate sale manager know, don’t you think? Should we really be the ones to do this?”

I shake my head.

“I don’t want to give it to someone else,” I say. “This might sound crazy but remember when you asked me if I was doing okay earlier?”

“Yeah.”

“I just had this feeling that, I don’t know, that there was something important about me being there, in Clyde Jones’s house. Beyond the fact that it was just amazing luck.”

“Like fate?” she asks.

“Maybe,” I say. “I don’t know. Maybe fate. It felt like it.”

Charlotte studies my face.

“Let’s just try,” I say.

“Well, it’s after ten. It would be almost eleven by the time we got there,” Charlotte says. “We can’t go tonight.”

I know as well as Charlotte that we can’t just show up on someone’s doorstep at eleven with an envelope from a dead man.

“My physics final is at twelve thirty,” I say. “Yours?”

“Twelve thirty,” she says.

“I can’t go after because I have to get that music stand and then get to set. I guess we’ll have to go in the morning.”

Charlotte nods, and we get out our phones to see how long it will take us to get to Long Beach. Without traffic, it would take forty minutes, but there is always traffic, especially on a weekday morning, which means it could take well over an hour, and we need to leave time for Caroline Maddox to tell us her life story, and we have to make sure we get back before our finals start, which means we have to leave . . .

“Before seven?” I say.

“Yeah,” Charlotte says.

We are less than thrilled, but whatever. We are going to hand-deliver a letter from a late iconic actor to a mysterious woman named Caroline.

Chapter Two

We get on the road at 6:55, glasses full of Toby’s iced tea because it was either that or some homemade kombucha that neither of us was brave enough to try. Toby does yoga, eats lots of raw foods. It’s one of the areas in life where we diverge, which is probably good since we’re alike in almost every other way: a love for the movies, a love for girls, an energy level other people sometimes find difficult to tolerate for extended periods of time.

Charlotte and I spend a while in bumper-to-bumper traffic on the 405. I allow Charlotte twenty minutes of public radio, and then when I am thoroughly newsed-out I turn on The Knife, because I am a firm believer that important moments in life are best with a sound track, and this will undoubtedly be one of those moments.

“Who do you think she is?” I ask, switching into the right lane. Charlotte’s holding Clyde’s envelope, studying Caroline’s carefully written name.

“Maybe an ex-girlfriend?” she says. “She’ll probably be old.”

I try to think of other possibilities, but Clyde Jones is famous for being a bit of a recluse. He had some high-profile affairs when he was young, but that’s ancient history, and it’s common knowledge that he died without a single family member. With relatives out of the question, I can’t think of many good answers.

We exit the freeway onto Ruby Avenue.

“I’m getting nervous,” I say.

Charlotte nods.

“What if it’s traumatic for her? Maybe it wasn’t the best idea to do this before our finals. What if Caroline needs us or she passes out from shock or something?”

“I doubt that will happen,” Charlotte says.

Neither of us has been on Ruby Avenue, so we don’t know what to expect. But we do know that as we get closer to the address it becomes clear that whoever Caroline Maddox is, she doesn’t live the same kind of life Clyde did. Number 726 is one of those sad apartment buildings that look like motels, two stories with the doors lined up in rows. We park on the street and look at the apartment through the rolled-up window of my car.

“Maybe she’ll be someone he didn’t know that well. Like a waitress from a restaurant he went to a lot. Or maybe he had a daughter no one knew about. From an affair or something.”

“Yeah, maybe,” Charlotte says.

We get out of the car.

After climbing the black metal stairs to the second story and knocking on the door of apartment F, I whisper, “Is it okay for us to ask what’s inside? Like, to have her open it in front of us?”

Charlotte shakes her head no.

“Then how will we ever know? Will we follow up with her?”

“Shhh,” she says, and the door opens to a shirtless man, holding a baby on his hip.

“Hello,” Charlotte says, professional but friendly. “Is Caroline home by any chance?”

The guy looks from Charlotte to me, shifts his baby to the other hip. He has longish hair, a shell necklace. A surfer who ended up miles from the beach.

“Sorry,” he says. “No Caroline here.”

Charlotte looks at the address on the envelope. “This is 726, right?”

“Yeah. Apartment F. Just three of us, though. Little June, myself, my wife, Amy.”

“Do you mind my asking how long you’ve lived here?” Charlotte asks.

“About three years.”

“Do you know if a Caroline lived here before you?”

He shakes his head. “I think a dude named Raymond did. We get his mail sometimes.”

I turn to Charlotte. “Maybe she left a forwarding address with the landlord.”

She turns to the surfer. “Does the manager live in the building?”

He nods. “Hold on,” he says, disappears for a moment, and returns without the baby. He slides on flip-flops and joins us outside. “It’s hard to describe. I’ll lead you there.”

We follow him down the stairs.

“Awesome weather,” he says.

I say, “Well, yeah. It is LA.”

“True,” he says.

We walk along a path on the side of the building until we reach a detached cottage. He knocks on the door. We wait. Nothing.

“Hmm,” he says. “Frank and Edie. They’re old. Almost always home. Must be grocery day.”

He pulls a phone out of his pocket.

“I can give you their number,” he says, scrolling through names, and Charlotte enters it into her phone.

~

Walking back to the car, I say, “If we can’t find Caroline, are we allowed to open the envelope?”

“We should really try to find her.”

“I know. But if we don’t.”

“Maybe,” she says. “Probably.”

I hand Charlotte my keys and she unlocks her side, gets in, leans over and unlocks mine. I start the car and look at the time.

“We could have slept an extra hour,” Charlotte says.

“Let’s call the managers now,” I say. “Maybe they were sleeping.”

But she calls and gets their machine. “Good morning,” she says. “My name is Charlotte Young. I’m trying to get in touch with a former tenant of yours. I’m hoping you might have some forwarding information. If you could call me back, I would appreciate it.”

She leaves her number and hangs up.

Sometimes she sounds so professional that I can’t believe the girl talking is also my best friend. At work, as long as I do my job well I don’t have to talk like an adult because I’m one of the creatives. But Charlotte helps with logistics and phone calls and scheduling and making sure people show up when they are supposed to.

“I hope they call back,” I say, noticing a brief ebb in the traffic and making a U-turn in the middle of the block.

“I’ll follow up if they don’t,” Charlotte says.

“But if we can’t reach them, and we can’t find Caroline, then we’ll open the letter,” I say. “Right?”

“Maybe,” she says. “But we’re really going to try to find Caroline.”

~

After my physics final and my Abbot Kinney stop, I drive to the studio, a little nauseous. Heartbreak is awful. Really awful. I wish I could listen to sad songs alone in my car until I felt over her. But I can’t even talk about it with Charlotte, and I have to finish designing the room I’m working on now, even though I know Morgan will be on set with her sleeves pushed up and her tight jeans on and her short hair all messy and perfect. I pull into the studio entrance and the guard waves me through, and I roll past Morgan’s vintage blue truck and into an open spot a few cars away, trying not to think of the first time I sat in the soft, upholstered passenger’s seat and all the times that followed that one.

Morgan is off in a far corner of the set, but I see her first and then she’s all I see. Filling everything. I’m carrying the music stand and I set it down in the room, but even though I’m looking at it and running my hand along its smooth wooden base, I can barely register that it’s here.

Ginger says something and I say something back. She laughs and I fake-laugh and then I move a picture frame over a couple inches and immediately move it back. And then Morgan is next to me asking if I got her texts, touching me on the waist in the way that makes my stomach feel like a rag someone is squeezing.

I nod. Yes. I got them.

“I miss you,” she says.

I don’t say anything back because we’ve done this so many times before and I promised myself that I wouldn’t do it again. She can’t break up with me and then act like she’s the one who’s hurt. All I want is to flirt with her on set, to ride around in her cute truck talking all day, and dance with her at parties and lay poolside at her apartment and kiss. All the things we used to do. All the things we could be doing now if she weren’t busy wondering if the world holds better things for her than me.

“Your shirt’s cute,” she says, but I don’t say anything, just lean over to smooth down the edge of the colorful, patterned rug we’re standing on. This morning I tried on seven outfits before deciding on these cute green shorts and this kind of revealing, strappy white tank top. I thought it looked summery and fun and, I’ll admit, really good on me. But now I think I should have worn something I always wear so that Morgan wouldn’t notice it was different and thus I wouldn’t appear to be trying to look different.

I bend down to adjust the rug again, and it really does look good, the way the green in the music stand brings out the colors in the pattern, and I’m finding myself actually able to think of something other than her until she says, “Emi, are you not talking to me?”

And I stand up and say, “No, no, that’s not it.”

Because it isn’t. I’m not trying to be childish or standoffish. I’m not trying to be mean. But I can’t tell her that I’m not talking because I’m afraid that I’ll cry if I do. The humiliation of being broken up with six times is brutal. And really, there might not be much worse than being at work with all of the people whose respect you want to earn while your first real love tells you you look pretty because she wants you to feel a little less crushed by the fact that she doesn’t love you back.

I force a smile and say, “Check out this stand. Isn’t it perfect?” knowing that she’ll like it almost as much as I do.

“Yeah,” she says. “The whole room looks really, really good.”

I take a step back and look at it. Morgan’s right. The room is supposed to be the basement practice space for a teenage-band geek named Kira. She doesn’t have a big part in the movie, but there’s an important scene that takes place in this room, and it’s the first set I’ve designed on my own. I started with actual kid stuff. Trophies from thrift stores that I polished to make seem only a couple years old. Concert posters of a couple popular bands whose members play trumpets, which this character plays. So much sheet music that it’s spilling off shelves, piled on every available surface. All of these normal things, but then a few extravagances, because this is the movies. A white bubble chandelier that lets out this beautiful soft light; a really shiny, really expensive trumpet; a hand-woven rug. And now, the music stand. I feel overwhelmingly proud of myself for pulling this off, and completely in love with the movie business.

“So now you’re just waiting on the sofa?”

I turn to the last empty wall where the sofa will go, and nod.

“Any leads?”

I shake my head. No.

“It needs to be perfect,” I say.

Early in the movie, Kira loses her virginity. She loses it to a guy who doesn’t love her, but she doesn’t know that in the moment. They have sex, not in her bedroom, but on a sofa in this practice room, the room that I am dressing, and I know that the scene will be disturbing because the secret is out to everyone except Kira that the guy isn’t worth losing anything to. I’ve been trying to track down the sofa since I got the assignment. I know what I want. I know that it’s going to be a vivid green, a soft material. The scene will be painful but the sofa will comfort her. It needs to be worn-in and look a little dated because it’s the basement practice room; it’s where the cast-off furniture goes after it’s been replaced by newer and better things. But it also needs to be special enough to have been saved.

From across the studio, a guy calls to Morgan, asking her a question about plaster. Morgan is a scenic, which means that she builds the decorative elements of the sets before people like me come along and fill them. She can turn clean, white walls into the crumbling sides of a castle. She can turn an indoor space into a garden. She’s an artist. It hurts to be this close to her.

“I have to go help him,” she tells me. “But maybe we can grab dinner later. Talk. I’ll check back in before I’m off ?”

I nod.

She walks away.

Then I text Charlotte: Intervention needed.

Luckily, Charlotte’s on the lot, working a couple buildings over. She tells me to meet her in the parking lot at exactly six o’clock.

~

After a couple hours of tinkering with my room and helping some of the set dressers, I say good-bye to Ginger (who tells me for the twentieth time how great everything looks) and find Morgan outside with her hands covered in plaster.

I tell her, “Charlotte needs my help, so I’m not going to be able to have dinner. We’re in the middle of this really crazy mystery.”

I wait for her to ask what it is. I get ready to say, We’re trying to fulfill Clyde Jones’s dying wish, for the awe to register on her face. But she just says, “No problem. Another time.”

Another time. A period, not a question mark. As if it’s such a sure thing that I will say yes.

I back my car up alongside Charlotte’s so that, with our driver’s side windows open, we can talk to each other without getting out.

“Thanks,” I say.

“Anytime I can save you from making yet another terrible mistake with that girl please let me know,” she says. Which is a little harsh, but something I probably deserve.

“Did the old people call you?” I ask.

“No. I wanted to wait for you before trying again.”

I hop out of my car and cross around to hers. She puts her phone on speaker and dials. It rings. We wait. And wait. And then an old man’s loud voice says hello.

“Hi,” Charlotte says. “I’m sorry to bother you. I left you a message this morning. My name is—”

“Hey, Edie!” the man yells. “It’s that girl from this morning! Calling us back!”

Charlotte and I widen our eyes in amusement.

“Now,” Frank says. “I couldn’t quite make out your phone number in the message. Yes! The girl from this morning! Let me see if I can find what I wrote down. Tell me the number again?”

Charlotte tells him.

“Oh,” he says. “Two-four-three. I thought you said, ‘Two-oh-three.’”

“Actually, it is two-oh-three.”

“Two-four-three, yes.”

“Actually—”

“And your name one more time, my dear?”

“Charlotte Young. I was wondering if you had any information—”

“Yes, dear! We had the number wrong! And her name is Charlotte!”

I’m trying my hardest not to laugh but I can see Charlotte becoming serious. She switches off the speakerphone and holds it to her ear.

“Frank? Sir?” she asks. “Will you be home for a little while? I have some questions that might be better to ask in person.”

I wait.

“Okay. Yes. Hello, Edie. My name is Charlotte. Charlotte. Yes, it’s nice to talk to you, too.”

~

Frank and Edie are waiting for us on their porch when we arrive in Charlotte’s car. It took us a little over an hour to get there and I wonder whether they’ve been waiting this whole time, frozen in positions of expectancy.

“Now, which one of you is Charlotte?” Frank says.

“Don’t answer!” Edie says. “Don’t say a word, girls. I am an excellent judge of people. Let me guess.”

She peers at us. Her hair is a purple poof, like cotton candy. I can’t tell if it’s supposed to be brown or if she’s getting wild in her old age.

“You,” she says to me. “Are Charlotte.”

I shake my head.

“Emi,” I say, and hold out my hand.

She scoffs, says, “You look like a Charlotte,” but her eyes have this fun glimmer.

Frank towers over her, surveying us through thick glasses.

“Come on in, girls,” he says. “Come on in.”

Inside, we sit on a plastic-covered maroon sofa with People magazines stacked up beside us, cookies and lemonade arranged on the coffee table. This elderly couple having us into their living room, serving us snacks with the fan blasting and the screen door flapping open and shut—it’s so sweet, almost enough to take my mind off Morgan.

“I hope you like gingersnaps,” Edie says. She thrusts a finger toward Frank. “He got ginger cookies. I said I wanted plain.”

“They didn’t have plain.”

“How could they not have plain?”

“You were with me, dear,” he says. “Lemon. Oreo. Maple. Ginger. No plain.”

She shakes her head.

“Crap,” she says. She lifts a cookie and eats it. “Crap,” she says again. And then she takes another.

“Do you live in the neighborhood?” Frank asks us.

“I live in Westwood,” Charlotte says.

“Santa Monica,” I say.

“Santa Monica!” Edie says. “Our son, Tommy, lives in Santa Monica. You may know him. Tommy Drury?”

I shake my head. “No,” I say. “He doesn’t sound familiar.”

“He’s a lovely boy,” Edie says.

“He just turned sixty!” Frank says. “He’s not a boy!”

“He’s my boy. Do you shop at the Vons on Wilshire?”

“Um,” I say. “I guess. I mean, my parents do.”

“It’s a good Vons,” Frank says.

“A nice deli section,” Edie agrees. “But too crowded.”

Charlotte compliments them on the lemonade (“Straight out of the box!” Edie confides) and then says, “We’re looking for a former tenant of yours. Caroline Maddox.”

“Who?” Frank turns to Edie, and it’s only then that I notice his hearing aids.

“Caroline Maddox,” Edie shouts.

“Oh yes, Caroline.” Frank nods.

“You remember her?” Charlotte asks.

“Yes, of course!” Edie says. “She was a very nice girl. Very nice. But she had troubles. The drugs and the men and that baby.” She shakes her head. “What a shame.”

Frank says, “Yes, yes. You girls must have noticed that the hedges around the path are all overgrown.” He says it so apologetically. “Caroline, she used to take care of those for us. It was years ago and I worked during the days and dealt with apartment business at night. Caroline, she helped us with some of the chores.”

“For reduced rent,” Edie adds.

“Do you know where she is?” Charlotte asks. “Or where she moved to after she left the apartment?”

“Oh, dear,” Edie says.

“Oh, dear,” Frank echoes. “I hate to say it, but Caroline died.”

“When?” Charlotte asks.

Frank shakes his head. “I’m terrible with dates,” he says.

“I know,” Edie says. “It was October of 1995. I remember because the Dodgers lost in the playoffs. Those Braves beat them Three to nothing. Three to zip. Terrible! I remember thinking, What could be worse than this? And then, just a few days later, we found Caroline in the apartment.”

Frank looks off to the side, eyes glassy, and Edie picks up a cookie but doesn’t eat it. We sit quietly for a little while, and then Edie begins gossiping about celebrities. I tell her about our jobs in the movies and she is impressed, especially with The Agency, which she’s already been reading about even though shooting doesn’t begin for a few months. But Charlotte stays quiet, and I can understand why. Here we were expecting to find Caroline, a living person, who would take this envelope from us and hopefully tell us about what was inside and who she was to Clyde. But instead we discover that Caroline is a dead woman. And it’s unsettling, somehow, that whatever Clyde wanted to give to her was never, and never will be, received.

~

It’s dark by the time we get back in the car.

Charlotte sighs. “I guess we did all we could.”

“So we’re going to open it?”

She nods, but doesn’t reach for her bag.

I find it on the backseat and fish out the envelope. It’s so thin. And I realize something that I hadn’t really registered before: It’s old, yellowing. I wonder how old. Old enough, I guess, for Caroline to die and someone named Raymond to move in and move out, and then for the surfer’s family to follow. Maybe even older than that.

Charlotte takes the keys from her lap and very carefully rips open the envelope.

Dear Caroline,

I confess it was optimistic of me to think our lunch might transform a lifetime of estrangement into some kind of relationship. I don’t think, however, that it was optimistic to think it could have been some kind of beginning, even if it was the beginning of something meager. A casual hello now and then. An acquaintanceship. But I’ve been trying to reach you for several months. My letters have been returned. What few phone numbers I can find for you are all outdated. I’m not disregarding the possibility of a change of heart, but, for now at least, I’m giving up.

There were things I wanted to tell you that afternoon that I couldn’t bring myself to say. I told myself it was because I expected it to be Me and You, and instead it was Me and You and Lenny. So I found myself in the company of two strangers instead of only one. However, that might have only been an excuse. You are my only child and I was never a father to you. I don’t know how a father is supposed to say heartfelt things or express regret or give a compliment.

So, here it goes, on paper, which feels far less daunting.

I was unaware of your existence when you were born. After I learned about you, I had intentions of being a good father. To put it plainly, your mother made that impossible.

She would not accept my money. She would not consider a friendship. I spent a decade trying to make amends with her but the truth is that I had very little to say. We both had our reasons for what happened that night and in the few weeks that followed. I won’t presume to know hers, but in my defense, I did not make any promises or intentionally lead her on. She had what many people crave, a few minutes in the spotlight on the arm of someone famous. She did not ever know me and I did not ever know her. I would like to think that we each received something we needed in a specific period of time in our lives, but I fear that your mother’s reaction to my repeated gestures spoke otherwise.

It may seem unfair of me to speak this way of a woman who is no longer in this world to defend herself. I don’t wish to be cruel. Another thing I wanted to do (but didn’t) was offer you my condolences. And I wanted to say that I know what it’s like to be an orphan. It’s possible that you feel alone in the world. I know a little bit about that, too. I suppose I thought we might bond over our specific tragedies, but instead I told you about my dogs and the weather, and you stared at your eggs and never touched them.

You are my only child. I wanted you to know a few things about me. It is true that I always wear a cowboy hat, but I am not the stoic, humorless man that I so often played. I try my best to enjoy life. I enjoy hiking through the hills behind my home. I have loved deeply, but had hopes of a different kind of love.

There is a bank account in your name at the Northern West Credit Union. Please visit them and ask for Terrence Webber. He will give you access to the account. If you do not want the money, please give it to Ava. It may seem crass to give you so much. Please don’t think of it as an attempt to buy your love or forgiveness. Despite the idealistic notion that money is of little importance, money can open doors. I hope, my daughter (if you’ll allow me to call you that this once), that doors will open for you all your life.

My regards,

Clyde

“So you were right,” Charlotte says. “Caroline Maddox was his daughter.”

“What tragedy,” I say.

“So bitter,” Charlotte says.

“So regretful.”

Charlotte nods. “It’s like he wants to tell her everything but it hardly adds up to anything.”

“I know. I wear cowboy hats? I enjoy hiking?” I pick up the letter again. His handwriting is careful and shaky and everything is neat, like he wrote multiple drafts. “Who’s Lenny? Who’s Ava?”

Charlotte shakes her head. “I don’t know.”

At the end of the block, a couple men step out of a liquor store, shouting into the night. They laugh, slide into their car, pull away.

“He didn’t even know that she died,” I say.

We head back to the studio to pick up my car, and then we caravan to Toby’s apartment, where our parents told us we could stay again tonight, and where we intend to stay for as long as Toby’s away.

Driving alone, I can’t but help thinking of how today is just so sad. Toby’s gone, Morgan doesn’t love me, Clyde Jones had a daughter named Caroline who tended Frank and Edie’s garden and had problems with men and drugs and never got her father’s letter or all that money that might have helped her.

And I was sure that all of this would mean something for me, too. That something had to come of wandering through Clyde’s house, of our accidental discovery. But now it’s just something else that has come to an end.

And it’s only later, after watching Lowlands, with the warm breeze coming through the kitchen door and our glasses half full of Toby’s Ethiopian tea, that Charlotte says, “What was it Edie said? The drugs and the men and that baby? Could Ava be Clyde’s granddaughter?”

Copyright © 2015 by Nina Lacour. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.