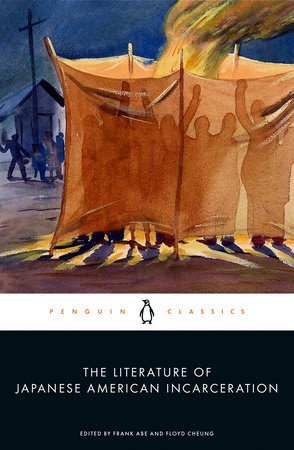

Preface by Frank Abe and Floyd Cheung

THE LITERATURE OF JAPANESE AMERICAN INCARCERATION

PART I: BEFORE CAMP

Introduction to Part I

Arrival and Community

1. Henry (Yoshitaka) Kiyama, “Arrival in San Francisco” and “The Turlock Incident”

2. Ayako Ishigaki (as Haru Matsui), “Whither Immigrants”

3. Toshio Mori, “Lil’ Yokohama”

Arrest and Alien Internment

4. Shelley Ayame Nishimura Ota, “Those Airplanes Outside Aren’t Ours”

5. Kamekichi Tokita, “1941 (Showa 16)”

6. John Okada (as Anonymous), “I Must Be Strong”

7. Bunyu Fujimura, “Arrest”

8. Fujiwo Tanisaki, “They Took Our Father Too”

9. Otokichi Ozaki (as Muin Ozaki), “Fort Sill Internment Camp”

10. Yasutaro Soga (as Keiho Soga), “Sand Island and Santa Fe Internment Camps”

11. Iwao Matsushita, “I Can’t Bear to Be Stigmatized as ‘Potentially Dangerous’ ”

Cooperation and Refusal EXECUTIVE ORDER

12. James Omura, “Has the Gestapo Come to America?”

13. Mike Masaoka, “Decision to Cooperate” 50 INSTRUCTIONS TO ALL PERSONS OF JAPANESE ANCESTRY

14. Gordon K. Hirabayashi, “Why I Refuse to Register for Evacuation”

15. Charles Kikuchi, “Kicked Out of Berkeley”

PART II: THE CAMPS

Introduction to Part II

Fairgrounds and Racetracks

16. Monica Sone, “Life in Camp Harmony”

17. Mitsuye Yamada, “Curfew”

18. Portland Senryū Poets, “Resolution and Readiness, Confusion and Doubt”

19. Yoshio Abe, “Lover’s Lane”

Deserts and Swamps RECOMMENDATIONS TO MILTON EISENHOWER, DIRECTOR, WAR

RELOCATION AUTHORITY

20. Lily Yuriko Nakai Havey, “Fry Bread”

21. Toyo Suyemoto, “Barracks Home”

22. Authorship uncertain, “That Damned Fence”

23. Kiyo Sato, “I Am a Prisoner in a Concentration Camp in My Own Country”

24. Masae Wada, “Gila Relocation Center Song”

25. Cherry Tanaka, “The Unpleasantness of the Year”

26. Hiroshi Nakamura, “Alice Hasn’t Come Home”

27. Joe Kurihara, “The Martyrs of Camp Manzanar”

28. Iwao Kawakami, “The Paper”

29. Nao Akutsu, “Send Back the Father of These American Citizens”

Registration and Segregation STATEMENT OF UNITED STATES CITIZEN OF JAPANESE ANCESTRY

30. Topaz Resident Committee, “We Respectfully Ask for Immediate Answers”

31. Kentaro Takatsui, “The Factual Causes and Reasons Why I Refused to Register”

32. Sada Murayama, “Loyalty”

33. Mitsuye Yamada, “Cincinnati”

CONFIDENTIAL STATEMENT TO DILLON MYER, DIRECTOR, WAR RELOCATION AUTHORITY

34. Kazuo Kawai (as Ryōji Hiei), “This Is Like Going to Prison”

35. Noboru Shirai, “The Army Takes Control”

36. Hyakuissei Okamoto, “Several brethren arrested after martial law was declared at Tule Lake in November 1943”

37. Violet Kazue de Cristoforo, “Brother’s Imprisonment”

38. Tatsuo Ryusei Inouye, “Hunger Strike”

39. Bunichi Kagawa, “Geta”

Volunteers and the Draft

40. Minoru Masuda, “A Lonely and Personal Decision”

41. Tamotsu Shibutani, “The Activation of Company K”

42. Toshio Mori, “She Is My Mother, and I Am the Son Who Volunteered”

43. Jōji Nozawa, “Father of Volunteers”

44. Fuyo Tanagi and the Mothers Society of Minidoka, “Petition to President Roosevelt”

45. Yoshito Kuromiya, “Fair Play Committee”

46. Frank Emi and the Fair Play Committee, “We Hereby Refuse . . . In Order to Contest the Issue”

47. Eddie Yanagisako and Kenroku Sumida, “Song of Cheyenne”

Resegregation and Renunciation AN ACT TO PROVIDE FOR LOSS OF UNITED STATES NATIONALITY UNDER CERTAIN CIRCUMSTANCES.

48. Noboru Shirai, “Wa Shoi Wa Shoi, the Emergence of the ‘Headband’ Group”

49. Motomu Akashi, “Badges of Honor”

50. Joe Kurihara, “Japs They Are, Citizens or Not”

51. Hiroshi Kashiwagi, “Starting from Loomis . . . Again”

PART III: AFTER CAMP

Introduction to Part III 223

Resettlement and Reconnection

52. James Takeda (as Bean Takeda), “The Year Is 2045”

53. David Mura, “Internment Camp Psychology”

54. Shizue Iwatsuki, “Returning Home”

55. Toyo Suyemoto, “Topaz, Utah”

56. Janice Mirikitani, “We, the Dangerous”

57. Amy Uyematsu, “December 7 Always Brings Christmas Early”

58. Brian Komei Dempster, “Your Hands Guide Me Through Trains”

59. Christine Kitano, “1942: In Response to Executive Order 9066, My Father, Sixteen, Takes”

Redress

60. Shosuke Sasaki and the Seattle Evacuation Redress Committee, “An Appeal for Action to Obtain Redress for the World War II Evacuation and Imprisonment of Japanese Americans” 247 PERSONAL JUSTICE DENIED, PART 2: RECOMMENDATIONS

61. William Minoru Hohri, “The Complaint”

62. Jeanne Sakata, “Coram Nobis Press Conference” 260 LETTER FROM THE WHITE HOUSE

63. traci kato- iriyama, “No Redress”

Repeating History

64. Perry Miyake, “Evacuation, the Sequel”

65. Fred Korematsu, “Do We Really Need to Relearn the Lessons of Japanese American Internment?”

66. Brandon Shimoda, “We Have Been Here Before”

67. Brynn Saito, “Theses on the Philosophy of History”

68. Frank Abe, Tamiko Nimura, Ross Ishikawa, Matt Sasaki, “Never Again Is Now” 287

Acknowledgments

Suggestions for Further Exploration

About the Authors

Credits and Copyright Notices