One

Under the Sign

of Victory

It seems to me that God, with infinite wisdom and skill, is

training the Anglo-Saxon race for an hour sure to come . . .

¥ Rev. Josiah Strong, 1885

When the war is over we shall live in an Anglo-American world. There will be other great powers, but the sanctions on which the West reposes will be the ideas for which England and America have fought and won, and the machines behind them.

¥ Cyril Connolly

I saw Winston Churchill. On my seventh birthday, in 1958. My grandparents took my younger sister and me to see Peter Pan at the Scala Theatre in London. When she wasn't too drunk to perform, Sarah Churchill played Peter. Quite often she played Peter while drunk as well. Once, she audibly said "Fuck!" when she landed awkwardly after flying across the stage unsteadily on a wire.

Nothing like that happened on the afternoon we attended the play. Or if it did, I can't remember. What I do recall is the moment Sarah's father arrived. The memory is a kind of audiovisual blur: a pale face in the spotlight, a pudgy hand emerging from a fur muff to make the V sign, and everyone around me, including my very patriotic British grandparents, breaking into wild applause. (The fur muff is a detail I know only from the photograph published in the papers the next day.) Being Jewish, my grandparents felt strongly that Churchill had saved their lives. The extraordinary enthusiasm of that moment, the shining eyes and the raucous cheering for an old man in a theater box, has stayed with me; it was a bit like watching adults behave like rowdy children, which fitted the story of Peter Pan in a way, the boy who never grew up.

I must have had only a very vague idea who Churchill was. But reminders of the war were still around us: waterlogged bomb craters all over London, drunken soldiers from the British Rhine army throwing up on the ferry from the Hook of Holland to Harwich, and a steady diet of British comic books featuring dashing Spitfire pilots and beastly Germans. At home in The Hague, where I was born to a Dutch father, I assembled plastic Airfix models of Lancaster bombers. And British people we would meet at family parties in England still spoke to foreigners with the polite condescension that those who had lived through their finest hour still reserved for those who had been defeated.

Recent history was experienced by people of my age-I was born just six years after the war-largely as myth, in which Churchill played an important part. We were allowed a day off school to watch his funeral in black-and-white on television. This was just another reminder that we had been liberated from the Germans by people who spoke English. Canadians finished the job in the early spring of 1945, but American and British troops, as well as Canadians, had already entered the country from the south in 1944 and were dropped in the autumn of the same year along the Rhine in the disastrous Battle of Arnhem. Polish troops had played a heroic part, too, but this was not widely known. The language of freedom was English. Canadian troops were billeted in my paternal grandparents' house in Nijmegen, near Arnhem. The women danced with their liberators to Glenn Miller's "In the Mood." Hershey bars and silk stockings were liberally distributed in return for favors, which in many cases might have been granted anyway. And it was never forgotten that in the "hunger winter" of 1944-45, British and American bombers dropped onto a starving population bags of flour, corned beef, margarine, and chewing gum.

My own perception of Europe's liberation, like that of most people of my age, was largely shaped by the movies. Some of the most powerful cinematic memories bear little relation to artistic quality, or indeed historical accuracy. I still cannot watch The Longest Day, Darryl Zanuck's Hollywood reenactment of the D-Day landings, without weeping. All the Anglo-American stereotypes are there: Robert Mitchum, the macho Yankee chomping on a cigar while leading his men onto Omaha Beach; Sean Connery as a plucky Scottish private; Peter Lawford as Lord Lovat, accompanied by his own bagpiper-the very idea of a bagpiper playing under German fire is enough to reduce me to tears; John Wayne, dropped from the sky over Normandy to sort things out; and Kenneth More, the unflappable Royal Navy captain wading through the surf with his bulldog named Winston.

If the ghost of Churchill hovered around my childhood in The Hague, its presence was felt even more keenly in Washington, DC, and it lingered far longer. Presidents from John F. Kennedy to George W. Bush and beyond have hoped to follow the great war leader's example and save the world for democracy. His was the heroic myth they felt they had to live up to.

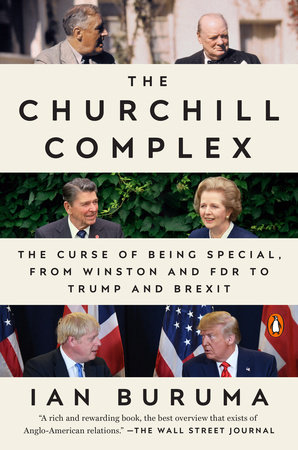

So tenacious has the aura of Churchill been that a political row erupted in 2016 over his bust in the Oval Office when Donald Trump was about to move in. Trump's people placed a bust of Churchill in the office with great fanfare, claiming that President Obama had replaced it with a bust of Martin Luther King Jr. Boris Johnson-the British politician who expressed warm feelings for Trump, wrote a shallow hagiography of Winston Churchill, encouraging flattering comparisons to the author, and would later become prime minister-attributed this "swap" to "an ancestral dislike of the British Empire." In fact, the sculpture that Obama replaced had been loaned to George W. Bush by Tony Blair, while an older bust of Churchill, once given by Britain to Lyndon B. Johnson, was being repaired. Obama quite properly gave the new bust back once the old one was restored. Now the old bust perches behind the desk of Trump, whose scowl might be mistaken for an attempted impersonation of Churchillian gravitas.

Churchill the man has been more popular in the US than his country ever was. Even presidents who had little time for the British revered Churchill. There are several possible reasons for this. Churchill's own (belated) sentimental feelings for the native country of his beloved mother, Jennie Jerome from Brooklyn, New York, were often expressed in flowery speeches all over the US. His frequent references to "the English-speaking peoples" and Anglo-Saxon "kith and kin" no doubt appealed to Americans of a certain age and class. But Churchill's main attraction, I believe, lies in the same myth that colored my childhood, which ties in closely to the view many Americans have of themselves: the beacon of liberty, the city on the hill, the land of the brave, the exceptional nation that freed the world from dictators. Churchill, although only half-American, became the symbol of this defiance of tyranny. He is the bulldog face of Anglo-American notions of valor.

Another ghost haunts Washington, DC, as well as London, along with Churchill's. Indeed the two are intimately linked. That is the ghost of Munich, the city where the British prime minister Neville Chamberlain signed an agreement with Hitler in September 1938 that allowed Germany to take a chunk of Czechoslovakia with impunity. Chamberlain thought he had bought "peace for our time." Churchill, speaking in Parliament, called it a "total and unmitigated defeat." He thought this "bitter cup" could be averted only once Britain recovered its "moral health and martial vigor" and arose again to take a "stand for freedom as in the olden time."

It is possible, as some maintain, that if Britain and France had taken that stand in 1938, Hitler's ambition of conquering Europe would have been thwarted. Others continue to argue that Chamberlain had no choice, since Britain was not ready to fight a war against Germany, and the US was in no mind to get involved. But the mythical verdict, still repeated in political speeches, and celebrated in the movies, is that Chamberlain was a shortsighted and cowardly appeaser and Churchill the hero. Ever since, whenever a foreign crisis has loomed, from the Suez Canal to the Korean peninsula, from Vietnam to the Falkland Islands, and from Bosnia to Iraq, the specter of Munich is invoked by Anglo-American leaders who want to go down in history as Churchill, not Chamberlain.

Churchill is often credited with coining the phrase "Special Relationship." He certainly made it popular, if only to convince the Americans to come to Britain's rescue in the perilous early years of World War II. Since then, despite Churchill's mythical spirit living on in the White House, the Anglo-American relationship has been more special in London than in Washington. Given the growing gap in relative power and influence between the two countries, this was inevitable. Indeed, as Britain's power waned, clinging to the Special Relationship was one way for the British to maintain an illusion that the glow of its finest hours under Roosevelt and Churchill had not been totally extinguished. British leaders might have been reduced to playing a steadily diminishing and sometimes demeaning role of impoverished but worldly-wise Greeks in the American Rome, but in their own eyes at least, this still allowed them to sup at a higher table than the other Europeans.

Britain's tortured relationship with the European continent, resulting at this time of writing in acrimonious wrangling over Brexit, is partly the result of Britain's nostalgia for the Special Relationship. Churchill himself spoke out in favor of a united Europe in 1946, even though he was vague about Britain's participation, but his spirit has made it harder for Britain to regard itself as a European nation on par with Germany or France, and to find its proper place in common European political and financial institutions.

There are many ways to chronicle the Special Relationship between Britain and the United States since they joined forces in World War II. One would be to examine the history of close cooperation between the British and American intelligence agencies. Another would be to describe the building of international financial institutions, such as the IMF and the World Bank. One of the promises made by Churchill and Roosevelt in their Atlantic Charter of 1941 was "global economic cooperation." Defeating Hitler, fascism, and the Japanese Empire was an internationalist enterprise. The postwar order, solidified in the Cold War, was set up by Britain and the US to defend democracies against their despotic enemies. If an anti-Communist despot was supported nonetheless, as long as he served Anglo-American interests, this was generally regarded in Washington and London as a necessary form of hypocrisy.

However, this book is not a history of institutions. I have chosen to write about the evolution and erosion of an idea, the Anglo-American myth that I grew up with. All US and British leaders have been touched by the history of World War II, even those who were not yet born when Roosevelt and Churchill drew up the Atlantic Charter. The story of those leaders and how they related to one another is also the story of their respective countries and how they affected the rest of the world, west as well as east.

It is my view that the shared myth has been both magnificent and a curse. History can inspire but also bedevil. How a wartime alliance that defeated Hitler, with the indispensable help of Stalin's Red Army, ended up after more than half a century of peace and prosperity in the West in the dispiriting and dangerous bluster and self-delusion of Trump and Brexit, is a melancholy tale. Britain and the US, despite all their flaws, were once regarded as models of openness, liberalism, and generosity. Even if they by no means always lived up to these ideals, the two English-speaking nations still offered some hope for what the Hungarian-born writer Arthur Koestler once called "the internally bruised veterans of the totalitarian age."

Now, perhaps only for the time being, the internationalist ideals set out in the Atlantic Charter have made way for populist agitation against immigrants, a hugely destructive British divorce from Europe, and an American president whose greatest wish is to build a big wall to keep the tired, poor, huddled masses from entering the US. Enoch Powell, a British Tory politician who held many reprehensible views, said once, quite wisely, that all political lives end in failure, "for that is the nature of politics and human affairs." The same might be said of the hopes of once great nations. That doesn't make those hopes any less admirable.

Two

Blood and History

Let not England forget her precedence of teaching nations

how to live.

¥ John Milton (to Parliament)

Before World War II, there was not much love lost between the British and Americans. Few people had the means to travel across the Atlantic. Historic wounds-the Boston Tea Party, wars of independence, 1812-were, if not fresh, still remembered in America. True, the US had joined the Allies in World War I in 1917 as an "associated power," and left more than fifty thousand dead on European soil (another sixty thousand died of disease, most because of the flu epidemic in 1918). But German and Irish Americans, and quite a few other "hyphenated" citizens not of British stock, had reason to be bitter about being made to feel like suspect outsiders in their own country. The great American journalist H. L. Mencken, who still spoke German with his parents, was so bruised by this experience that he later refused to see the conflict with Hitler's Germany as anything but "Roosevelt's war."

American Anglophilia existed, of course, but as in Europe, it was mostly a form of snobbery, a kind of mimicry of upper-class manners, popular among East Coast elites, the kind of people who sent their sons to English-style boarding schools and later to the pseudo-Gothickry of Ivy League universities. In his History of the American People (1902), Woodrow Wilson, a Southerner of Scots-Irish extraction, and the man responsible for getting his country into the European war, extolled the special virtues of "the self-helping race of Englishmen." This splendid race, he enthused, having outsmarted the wily French, provided the necessary backbone to the New World. In 1918, after the war was won, Wilson was stung by domestic criticisms that he had been too easily swayed by British interests. And so, at a victory banquet given to him at Buckingham Palace by King George V, he tempered his earlier sentiments: "You must not speak of us who come over here as cousins, still less as brothers; we are neither. Neither must you think of us as Anglo-Saxons, for that term can no longer be rightly applied to the people of the United States."

When the British in 1940 and '41, desperate for American help in a war that threatened to overwhelm them, used their finest rhetoric about common values, the shared English language, and the Anglo-American love of freedom, most Americans refused to be drawn in. Many were wary of being outwitted by the silver-tongued British, and suspicious that Britain was fighting selfishly to preserve its empire, for which few Americans felt any affection. In late 1941, General George Marshall, chief of staff, was still not keen to give the British all they wanted. But even he felt that there was "too much anti-British feeling" among his military colleagues-"Our people were always ready to find Albion perfidious."

Copyright © 2020 by Ian Buruma. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.