Chapter Six

For the next month, we are like the Hakka—the guest people of China that Māma told me about, who migrated from place to place. I discover that my parents have more friends scattered across the entire eastern United States than I ever knew about.

After we leave Niagara Falls, we visit one of Gōnggong’s old friends in New York City, where he talks as much as he did before Nǎinai died. That’s when I realize we’re not just leaving behind good memories—maybe we are leaving bad ones behind, too.

In New Jersey, Māma makes us tour the castle-like brick buildings of Princeton University even though I won’t go to college for six more years. Bàba insists on stopping in Philadelphia to see the Liberty Bell, which is a lot smaller than I expected.

In Baltimore, my parents decide to splurge and have lunch at a café overlooking the harbor. “I come one crabcake, sauce on side,” Māma orders.

“What did you say?” the waitress asks. Māma repeats her order. The waitress shakes her head, a frown crossed with a smirk on her pasty face. “Learn to speak English.”

My parents’ cheeks are flushed, but they won’t make a scene.

I glare at the waitress. “Our English is fine,” I say. Because it is.

Their English isn’t “broken,” like some people claim. It’s a translation of what they would say in Mandarin, word for word. Sometimes I think English is the broken language, with all the exceptions to grammar and spelling rules, words borrowed from other languages, and messy conjugations.

My voice catches on a lump of beetles, but I push through it. “My mother would like the crabcakes with the sauce on the side, like she said.” I order for the rest of us, too, and shut my menu with a snap. The waitress grabs our menus without a word and leaves. When the food comes, another waitress serves us.

“It is good, Lan,” Bàba says. I don’t know if he means the crabcakes or my speaking for them. But I notice that they let me walk ahead and talk to the people in the ticket booths at the museums in Washington, DC.

They’re both quieter, at least during the day. At night, they continue to stay up late, catching up with old friends on years’ worth of news. When their friends ask questions about our future, like what kind of work they are looking for, Bàba says, “I’m going to become the next Chinese movie star,” which makes everyone laugh, since he’s never acted in his life. Māma tells them she’s going to be a professional poker player in Las Vegas, which I think is a dig at Fourth Uncle except that she would be really good at it. I can never tell what she’s thinking. When Bàba tells them about Nǎinai’s passing and selling the bakery, that’s when Gōnggong falls silent.

I wonder why we’ve never visited any of these people before, and then I realize the answer. The bakery. And the family. We always had the family around us. Now we don’t.

The thought makes me yearn to call Xing, but I don’t have a cell phone anymore. One more thing lost to the squabbles about money. Neither of my parents have called any of the aunts and uncles since we left. Asking to borrow their phones to call Xing feels like a betrayal.

Bàba zigzags across one state after another, chasing the setting sun. We climb up into the mountains of West Virginia, the trees changing from big leafy oaks to windswept spruces, the landscape a tapestry of different greens. I keep my window open so I can smell the sharp piney scent. The thin, cold air feels lighter and more alive than the heavy, wet air along the coast. Bàba takes deep breaths, too.

“Bìng cóng kǒu rù,” Māma says in warning. Technically, her saying doesn’t apply since I’m inhaling through my nose and not my mouth, but I understand that she thinks the cool air will make me catch a cold. I want to tell her that germs make people sick, not chilly temperatures. Instead, I take another long, slow breath.

Māma’s voice gets sharper. “Lan, qiān jīn nán mǎi yì kǒu qì.” Bàba shoots me an apologetic look, but I’m already rolling up my window. She’s not worried about me, she’s worried about Gōnggong, his mouth hanging open a little bit as he sleeps. She’s right—a thousand pieces of gold couldn’t buy another breath if he got sick. We can’t lose him, too.

As the miles fall away, so does Māma’s happy tourist attitude. Maybe it’s because she doesn’t have any friends who live this far west. Or maybe she’s afraid that being too happy will make the gods angry. Or maybe she’s actually worried about how she and Bàba will find jobs and make money. Only Bàba stays cheerful. He tells Māma we are on our very own “journey to the west,” like in the ancient Chinese novel.

I say goodbye to July from the back seat of the car, my head resting against the stack of boxes, and wake up to August in a parking lot. It’s the middle of the night. Yellow light from the lampposts streams through the windshield, and the car engine ticks softly, like an old clock winding down. Māma and Gōnggong are still asleep, but the driver’s seat is empty.

Bàba stands in front of a small building, staring through the large glass windows. I get out of the car and stretch, then walk toward him, my footsteps crunching on the gravel. He turns and smiles as I approach. He points, and I follow the path of his hand to a sign in the window. Help Wanted, it says in large red letters printed on a white background. Below, in black marker, someone has scrawled Pastry Chef. I take a step back and look up at the building. A wooden panel hangs above the door, the words Redbud Café painted in cursive with a flowering tree carved above them.

I turn back to Bàba. “You want to work here?” I ask.

He nods enthusiastically. “Three signs,” he says. I must look confused, because he holds up a finger. “First sign: They need a baker. I know how to do this job.” He smiles again, holding up a second finger. “Second sign: Name of café has ‘red’ in it. This is the luckiest color.”

He’s seeing extra meaning in the name of the restaurant, just like Third Aunt did in my story. Look where that got us.

But Bàba doesn’t notice my frown. He holds up three fingers. “Third sign: moon.” Startled, I look up and realize that streetlights aren’t making the parking lot glow—it’s the moon. It seems brighter out here in the countryside than back home in Boston. Bàba continues, “Full moon is a complete circle. It means that our journey is also complete.”

I blink, trying to take it all in. “We’re going to stop traveling? And live here?”

“Yes.” Bàba’s voice thrums with excitement. “Lan, I even found a house for us.”

“A house?” I’ve never lived in a house before. Never had a yard. It seems like it would be lonely to have all that space separating each family.

“Yes,” Bàba says again. “I drove all around this town while you were asleep. There is a house for rent. I saw the sign.”

Bàba goes to wake up Māma so he can show her the three signs and convince her that this small town is our new home. I should be happy that we won’t be guest people anymore. But the beetles scurry around and around in my stomach, upset and unsettled. Bàba said the house was a sign. That’s a total of four signs. Four is the unluckiest number because the Mandarin word for it, sì, sounds the same as the word for death. I want to remind Bàba about that, but I don’t.

While Māma exclaims over the full moon, I crawl back into the car. Bàba had called me Lan again. Just Lan. He hadn’t even noticed, but I had. Somewhere on the dusty road between Boston and this unknown town, with the heat rising off the highway like a poisonous mist, my parents had started calling me Lan.

My parents have always called me Lánlán—repeating the second syllable of a child’s name is a sign of affection in China. I feel a sharp ache inside, the bite of a hundred mandibles. We left Xing and Tiffi, the aunts and uncles, the bakery, Chinatown, and now—my childhood. Has my phoenix story changed the way my parents feel about me?

I look around at the dingy café, the dirt parking lot, the shuttered storefronts across the street. This is it, I guess. My fairy-tale ending.

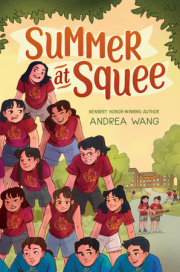

Copyright © 2021 by Andrea Wang. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.