PROLOGUE

The Woman in the Photograph

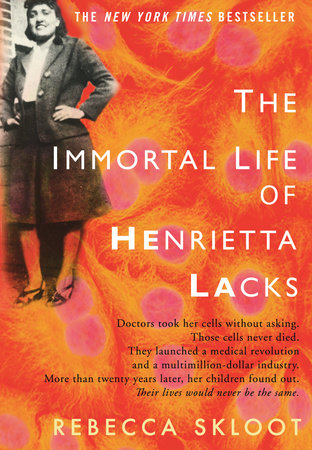

There’s a photo on my wall of a woman I’ve never met, its left corner torn and patched together with tape. She looks straight into the camera and smiles, hands on hips, dress suit neatly pressed, lips painted deep red. It’s the late 1940s and she hasn’t yet reached the age of thirty. Her light brown skin is smooth, her eyes still young and playful, oblivious to the tumor growing inside her—a tumor that would leave her five children motherless and change the future of medicine. Beneath the photo, a caption says her name is “Henrietta Lacks, Helen Lane or Helen Larson.”

No one knows who took that picture, but it’s appeared hundreds of times in magazines and science textbooks, on blogs and laboratory walls. She’s usually identified as Helen Lane, but often she has no name at all. She’s simply called HeLa, the code name given to the world’s first immortal human cells—

her cells, cut from her cervix just months before she died.

Her real name is Henrietta Lacks.

I’ve spent years staring at that photo, wondering what kind of life she led, what happened to her children, and what she’d think about cells from her cervix living on forever—bought, sold, packaged, and shipped by the trillions to laboratories around the world. I’ve tried to imagine how she’d feel knowing that her cells went up in the first space missions to see what would happen to human cells in zero gravity, or that they helped with some of the most important advances in medicine: the polio vaccine, chemotherapy, cloning, gene mapping, in vitro fertilization. I’m pretty sure that she—like most of us—would be shocked to hear that there are trillions more of her cells growing in laboratories now than there ever were in her body.

There’s no way of knowing exactly how many of Henrietta’s cells are alive today. One scientist estimates that if you could pile all HeLa cells ever grown onto a scale, they’d weigh more than 50 million metric tons—an inconceivable number, given that an individual cell weighs almost nothing. Another scientist calculated that if you could lay all HeLa cells ever grown end-to-end, they’d wrap around the Earth at least three times, spanning more than 350 million feet. In her prime, Henrietta herself stood only a bit over five feet tall.

I first learned about HeLa cells and the woman behind them in 1988, thirty-seven years after her death, when I was sixteen and sitting in a community college biology class. My instructor, Donald Defler, a gnomish balding man, paced at the front of the lecture hall and flipped on an overhead projector. He pointed to two diagrams that appeared on the wall behind him. They were schematics of the cell reproduction cycle, but to me they just looked like a neon-colored mess of arrows, squares, and circles with words I didn’t understand, like “MPF Triggering a Chain Reaction of Protein Activations.”

I was a kid who’d failed freshman year at the regular public high school because she never showed up. I’d transferred to an alternative school that offered dream studies instead of biology, so I was taking Defler’s class for high-school credit, which meant that I was sitting in a college lecture hall at sixteen with words like

mitosis and

kinase inhibitors flying around. I was completely lost.

“Do we have to memorize everything on those diagrams?” one student yelled.

Yes, Defler said, we had to memorize the diagrams, and yes, they’d be on the test, but that didn’t matter right then. What he wanted us to understand was that cells are amazing things: There are about one hundred trillion of them in our bodies, each so small that several thousand could fit on the period at the end of this sentence. They make up all our tissues—muscle, bone, blood—which in turn make up our organs.

Under the microscope, a cell looks a lot like a fried egg: It has a white (the

cytoplasm) that’s full of water and proteins to keep it fed, and a yolk (the

nucleus) that holds all the genetic information that makes you

you. The cytoplasm buzzes like a New York City street. It’s crammed full of molecules and vessels endlessly shuttling enzymes and sugars from one part of the cell to another, pumping water, nutrients, and oxygen in and out of the cell. All the while, little cytoplasmic factories work 24/7, cranking out sugars, fats, proteins, and energy to keep the whole thing running and feed the nucleus. The nucleus is the brains of the operation; inside every nucleus within each cell in your body, there’s an identical copy of your entire genome. That genome tells cells when to grow and divide and makes sure they do their jobs, whether that’s controlling your heartbeat or helping your brain understand the words on this page.

Defler paced the front of the classroom telling us how mitosis—the process of cell division—makes it possible for embryos to grow into babies, and for our bodies to create new cells for healing wounds or replenishing blood we’ve lost. It was beautiful, he said, like a perfectly choreographed dance.

All it takes is one small mistake anywhere in the division process for cells to start growing out of control, he told us. Just

one enzyme misfiring, just

one wrong protein activation, and you could have cancer. Mitosis goes haywire, which is how it spreads.

“We learned that by studying cancer cells in culture,” Defler said. He grinned and spun to face the board, where he wrote two words in enormous print: HENRIETTA LACKS.

Henrietta died in 1951 from a vicious case of cervical cancer, he told us. But before she died, a surgeon took samples of her tumor and put them in a petri dish. Scientists had been trying to keep human cells alive in culture for decades, but they all eventually died. Henrietta’s were different: they reproduced an entire generation every twenty-four hours, and they never stopped. They became the first immortal human cells ever grown in a laboratory.

“Henrietta’s cells have now been living outside her body far longer than they ever lived inside it,” Defler said. If we went to almost any cell culture lab in the world and opened its freezers, he told us, we’d probably find millions—if not billions—of Henrietta’s cells in small vials on ice.

Her cells were part of research into the genes that cause cancer and those that suppress it; they helped develop drugs for treating herpes, leukemia, influenza, hemophilia, and Parkinson’s disease; and they’ve been used to study lactose digestion, sexually transmitted diseases, appendicitis, human longevity, mosquito mating, and the negative cellular effects of working in sewers. Their chromosomes and proteins have been studied with such detail and precision that scientists know their every quirk. Like guinea pigs and mice, Henrietta’s cells have become the standard laboratory workhorse.

“HeLa cells were one of the most important things that happened to medicine in the last hundred years,” Defler said.

Then, matter-of-factly, almost as an afterthought, he said, “She was a black woman.” He erased her name in one fast swipe and blew the chalk from his hands. Class was over.

As the other students filed out of the room, I sat thinking,

That’s it? That’s all we get? There has to be more to the story.

I followed Defler to his office.

“Where was she from?” I asked. “Did she know how important her cells were? Did she have any children?”

“I wish I could tell you,” he said, “but no one knows anything about her.”

Copyright © 2010 by Rebecca Skloot. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.