Shay’s father climbed up into the driver’s seat of a rental truck and slammed the door. Started the engine, cut the emergency blinkers, then honked the horn twice to say goodbye, before pulling off. Moments later, another truck pulled up to the same spot—a replacement. Double-parked, killed the engine, toggled the emergency blinkers, rolled the windows up until there was only a sliver of space for air to slip through.

“What I wanna know is, why you get to give me one, but I can’t give you one?” Dante asked, leaning forward, elbows resting on his knees, his eyes on the street as the people in the new truck—a young man and woman—finally jumped out, lifted the door in the back, studied whatever was inside. Brooklyn was being its usual self. Alive, full of sounds and smells. A car alarm whining down the block. An old lady sitting at a window, blowing cigarette smoke. The scrape and screech of bus brakes every fifteen minutes. A normal day for Brooklyn. But for Shay and Dante, not a normal day at all.

“Oh, simple. Two reasons. The first is that I can’t risk getting some kind of nasty eraser infection. I’m too cute for that. And the second is that my dad will come back, find you, and kill you for marking me,” Shay replied, stretching her arms over her head, then sitting back down on the stoop beside Dante.

“Kill me? Please. Your pops loves me,” Dante shot back confidently. He wiped sweat from his neck, then snatched the pencil he had tucked behind his ear and gave it to Shay. They had been planning this ever since she got the news—ever since she told him she was leaving.

“Um . . . ‘love’ is a strong word. He likes you. Sometimes. But he loves me.” Shay pushed her finger into her own sternum, like pushing a button to turn her heart on. Or off.

“Not like I do.” Dante let those words slip from his lips effortlessly, like breathing. He’d told Shay that he loved her a long time ago, back when they were five years old and she taught him how to tie his shoes. Before then, he’d just tuck in the laces until they worked their way up the sides, slowly crawling out like worms from wet soil, which would almost always lead to Dante tripping over them, scraping his knees, floor or ground burning holes in his denim. Mrs. Davis, their teacher, would clean the wounds, apply the Band-Aid that would stay put only until school was over. Then Dante would slowly peel it off because Shay always needed to see it, white where brown used to be, a blood-speckled boo-boo waiting to be blown. Kissed.

•••

Shay smiled and bumped against Dante before turning to him and softly cupping his jaws with one hand, smushing his cheeks until his lips puckered into a fish face. She pressed her mouth to his for a kiss, and exaggerated the suction noise because she loved how kissing sounded—like something sticking together, then coming unstuck.

“Don’t try to get out of this, Dante,” she scolded, releasing his face. “Gimme your arm.” She grabbed him by the wrist, yanked his arm straight. Then she flipped the pencil point-side up and started rubbing the eraser against his skin.

They’d been sitting on the stoop for a while, watching cars pull out and new cars pull in. Witnessing the neighborhood rearrange itself. They’d been sitting there since Dante helped Shay’s father carry the couch down and load it into the truck. The couch was last and it came after the mattresses, dressers, and boxes with shoes or books or shay’s misc. in slanted cursive, scribbled in black marker across the tops. Up and down the steps Dante had gone, back and forth, lifting, carrying, moving, packing, while Shay and her mother continued taping boxes and bagging trash, pausing occasionally for moments of sadness.

Well, Shay’s mother did, at least. She couldn’t stop crying. This had been her home for over twenty years. This small, two-bedroom, third-floor walk-up with good sunlight and hardwood floors. A show fireplace and ornate molding. Ugly prewar bathroom tiles, like standing on a psychedelic chessboard. This was where Shay took her first steps. Where she took sink baths before pretending her dolls were mermaids in the big tub. Where she scribbled her name on the wall in her room under the window, before slinking into her parents’ bed to snuggle. This was where she left trails of stickiness across the floor whenever coming inside with a Popsicle from the ice-cream truck. Where she learned to water her mother’s plants. Plants they weren’t able to keep because now this space—their space—was gone. Bought out from under them. Empty. All packed into a clunky truck that was already headed south. And since Shay’s father left early to get a jump on traffic, it seemed like a good idea to let her mother take a much-needed moment to weep in peace.

Plus, then Shay could have a much-needed moment to eraser-tattoo Dante.

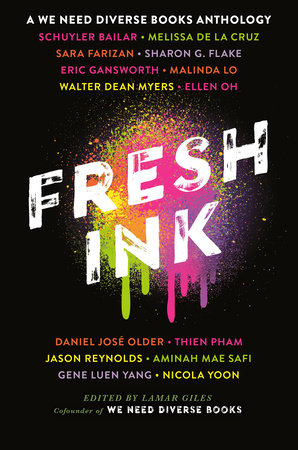

Copyright © 2018 by Lamar Giles. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.