LuckyMutt I am.

Irish and the black, black and the Irish, colored, Celtic, County Kerry, Afri-can!

What you sayin in there? call Grammy Brook from the front-room.

Nothin!

Talkin to yourself again, mutter Grammy Brook to herself.

Throw the cover off, jump outa bed, brrrrr! Woke up alone in the bed I share, alone in the bed in the bed-closet in the apartment in the tenement a Grammy Brook. Come out to the front-room grinnin.

Whatchu grinnin for? she ask, smilin. Then hold out somethin warm, somethin sweet: johnnycake! Happy birthday, birthday girl.

Thank you, Grammy! Careful—hot.

Ah!

Toldja—hot!

How old’s Miss Theo today? ask Mr. Freeman.

Seven!

Seven. That’s a good one. Mr. Freeman nod, Mr. Freeman our boarder sit in the chair havin his bread n coffee breakfast, his bedroll rolled up, rolled to the corner. Our apartment have two rooms: front-room and bed-closet. Our apartment have two rooms, two windas—both windas in the livin room facin the street, none in the bed-closet. Gran-Gran sit in her chair nex to the front winda near the door, Gran-Gran always at her winda lookin down on Park street. Gran-Gran is Grammy’s mammy.

So whatchu gonna do today, Miss Seven? Grammy ask, ironin her whites for the whites. The wet ones hung all over our apartment.

Door fling open, in come Hen. My cousin Hen, carryin in the pail.

Three, Hen say, then dump the water into Grammy’s pot on the stove. Hen strong! Hen only nine years of age, carryin the full water bucket: heavy! Soon as Hen empty it, she turn back around, head out our apartment, down the stairs for more.

I’d better be getting on to work, say Mr. Freeman.

All right, say Grammy.

I just want to say again how much I appreciate it, Mrs. Brook—you not raising the rent.

Didn’t get mine raised, no call to raise yours.

The barbering business not what it used to be, Mr. Freeman say, more to hisself. Then put his tin cup on the shelf and our barber boarder out the door.

I’ll sing a song for you, Grammy, that what I wanna do for my birthday!

Good girl. Grammy switch irons. Grammy tole me why ironin need two irons: one to use hot till it cool while the other gettin hot on the coals.

Hark! the herald angels sing!

Oh, that’s that new pretty one.

That song old, Grammy! Two years old, that song come to be when I was five!

New to old me.

Glory to the newborn King!

Your papa woulda been proud a you.

I knew she say that! Every time I have a birthday Grammy Brook smile teary and say my dead father her dead son Ezekiel woulda been proud a me.

In come Hen. Four, she say, emptyin the water into the pot. After five, I gotta get to work myself, Hen say and gone. When the water come to boilin, Grammy’ll dump it in the washtub and put in more a the white sheets and white towels for the white folks.

I gotta go to the necessary!

Bring me back a paper. Then Grammy careful count out her coin, sigh. I remember when it was the penny press. Now hard to find it under two.

But you gimme two cent and a half, Grammy.

The half-cent for you, birthday girl.

Thank you, Grammy!

Mijn gelukwenschen met uw verjaardag, say Gran-Gran, still lookin out the winda. Gran-Gran and Grammy useta be slaves with Dutch masters. I look at Grammy.

She wishin you good wishes.

Thank you, Gran-Gran! I’m seven!

Gran-Gran blink, not turnin her head from whatever’s happenin out on the street.

We live on the fourth floor: top! I skip down the steps, out to the back courtyard water-closets to wait in line, one two three four five six seven eight nine in front a me! Nine colored, our tenement all colored, nine in front a me, I gotta go! There’s Hen at the pump, Hen! I wave but she act like she don’t see me. Eight in front a me, I gotta go! Hen finish fillin the bucket and start luggin it back up to our apartment, seven in front a me, I gotta go! gotta go!

The little Brook girl hoppin, she gotta go bad, say Miss Lottie who live crost the hall from us. Then everybody let me go! Then I run out to see whatever’s happenin out on the street. The mornin boys hollerin.

New intelligence on the Bond street murder!

Bill passed for wagon road to the Pacific!

Latest on President-elect Buchanan’s picks for his cabinet! Read all about it!

I buy a two-penny press for Grammy Brook, run it up to her, run back to the street back to Park street, right on Baxter street. Five-story tenement and on the third floor: Grammy Cahill.

Maidin mhaith, Grammy!

Maidin mhaith, Theodora Brigid, say Grammy, smilin because she pleased I’m practicin my Good mornin in Irish.

It’s my birthday!

I know, little sprout. Seven is it?

I’m grinnin, noddin.

Lá breithe shona duit.

What’s that, Grammy!

Happy birthday.

Lá breithe shona duit, Theo! say Maureen and Cathleen.

May the saints be with ye, say Cousin Aileen, who’s my cousin Maureen and my cousin Cathleen’s ma.

Go raibh maith agat!

That’s how ye be thankin one person, Grammy correct me. More than one, ye say Go raibh maith agaibh.

Go raibh maith agaibh!

No, thank you for bein the livin spirit of herself, your dear mammy.

(I knew she’d say that! Every time I have a birthday Grammy Cahill smile teary and say I’m the livin spirit a my dead mother her dead daughter Brigid.) You’re after catchin me in the nick, mo leanbh, headin out to work. But I’m ready for ye. And she hand me a bite a cake.

Barmbrack! I chew it—still warm. Now Cathleen hold out her hand. A little something for the birthday girl, say Cathleen.

Ah! say everybody. Cathleen made me a doll! Little doll, jus tall as my wrist to my fingertip. My cousin Cathleen and her sister Maureen and their mammy Cousin Aileen is seamstresses,

Cathleen musta made my doll outa scraps from her work. Cathleen make pretty sewn things! Her mammy and sister work at the workshop but Cathleen gotta work the piecemeal at home: Cathleen’s fifteen years of age, and when she was six, she climbed a tree and fell and her legs stopped workin.

Go raibh maith agat, Cathleen!

You’re welcome.

Grammy Cahill headin out to work carryin her wares table, me skippin nex to her. Out to Baxter, then block and a half back to Park, set up her table, then send me to the grocer on Mott to pick her up a little flour. Crunch crunch through the Febooary sleet. Cross the road, I can do it! Look right and left for the carriages and carts. Look down for the horse manure and tenement manure. Look everywhere for the people rushin, pushin—hog runnin loose, everybody jump out the way! Buy the flour, back to Park, give it to Grammy. Then head six doors down the street: o’shea’s board & publick.

Mornin, Auntie Siobhan!

Well, good mornin to you, Miss Theo. Wonderin when you wander by, it bein the ninth of Feb.

I come near every day! Look what Cathleen gimme!

Aw, what a pretty doll baby. Care for a little birthday nog?

Yes! I can pay for it! Grammy Brook gimme a half-cent for my birthday! You save that for candy.

Thank you!

Better spend it today. Government claimin they’ll be endin the half-penny later this month.

No!

Spend it today.

I sit in my auntie’s tavern sippin my nog. Nutmeg! And a birthday apple! I’ll save it till later.

Tell me a story, Auntie Siobhan!

Em… Let me think.

(My colored family says um, my Irish family says em!)

A birthday story.

Right. Your mother’s birthday was—

May the twenty-fourth!

May the twenty-fourth. Woke up to a glory of a Wednesday and I said to my sister, Whyn’t you take off from that tyrant, we make a day of it in the park? The tyrant was—

Mrs. Bradley!

Told ye this one before, have I?

No!

Brigid was a day-maid, another girl lived there but your mother-to-be came home nights. Like all the fancy folks, Mrs. Bradley lived uptown—

Forty-first and Fifth!

And if your mother’d been older she’d never a done it, played hooky from her place of employ. If I’d been older I’d never a suggested it, but her newly sixteen and me two years behind so there we were, plannin the mischief. Walkin down to City Hall—

To the park!

And who we run into goin the other direction but Lily the cook! Brigid begged her to tell Mistress Scowlface she fell ill, promisin to return the favor one day. Your mother’d been workin for the beast a year, screamed at near daily, her face slapped for a vocal tone not pleasin to the lady or for disturbin the library’s alphabetical, placin a Charlotte Brontë before an Anne. Lily’d had her own troubles with the witch, don’t the Irish and the black always suffer it all? So Lily wished your ma a happy birthday and went on her way, and there we be: your mother and I and soft grass and crackers and whiskey. Laughin at some rough n tumble we’d seen at Mott street and Pell that mornin or at the people walkin by or at Brigid scrunchin up her face and makin her boss lady’s voice and that she just happened to be at when we look up to see none other than you know who!

Mrs. Bradley yell at my mother?

Herself was takin an afternoon stroll with her aul chum Mrs. Hyde, another one. Everything stops still, them starin at Brigid, the one supposedly home runnin a bout of fever. Then the old mistress heads straight toward my sister, chargin, her hand ready aimed to slap your poor mother’s cheek! Gets within three feet of her—and falls! Flat on her face, Lady Bradley is sherry-drunk middle of the afternoon—she of the Temperance Society! Then her companion comes to her aid, but appears aul Mrs. Hyde’s not exactly treadin steady ground neither! Finally Brigid helps her employer to her feet, and Mrs. Bradley yanks herself away, stumblin again with that, and the ladies depart. When they’re beyond hearin, we’re rollin, our stomachs torn up with the laughter! But next day, your mother trembles to show up for work, fearin she’ll be given her walkin papers.

My mother get sacked?

Auntie Siobhan shake her head, smilin.

The she-devil musta worried Brigid might someday have a mind to reveal that peculiar episode in the wrong company, so not only was your mother’s position secure but thereafter her tenure on Forty-first and Fifth proceeded appreciably more agreeable.

Not fair!

We turn to the man just entered the tavern from upstairs, tenant a the boarding-house.

Ye can’t just raise the rent every February the first, Siobhan!

The law says otherwise, my auntie answer him. Don’t go into effect till May, ye make your decision. ’Tis a wee increase, be no effort ye’d just re-budget your monthly liquor allowance.

Here I slip off the stool, out the door, leavin em to their shoutin.

How do ye, Theo!

Round the corner in the alley I see Nancy, smaller n me, standin with her brother, Elijah, smaller n her. They sleep in the alley crates since their mammy caught the influenza from the white folks she worked for and died. Nancy and Elijah skinny like sticks, eyes on my birthday apple. Now my eyes on my birthday apple. I take a nibble: sweet! Then give the rest to Nancy and Elijah who attack it, hungry-greedy. In my head I see Saint Peter in heaven markin this good deed on my list.

Your rich auntie give it to ya? ask Nancy, crunch. 16 KIA CORTHRON

One of em, I say. Now off to see the other.

Uptown I head: twenty blocks north, forty blocks and more, up to the country. At Fifty-ninth, Broadway change its name to Bloomingdale, still I keep goin. Eighty-sixth and Seventh, knock knock! Nothin. Knock knock! Then I remember: today’s Monday—my auntie at school!

Good mornink, Theo!

I turn around.

Good morning, Mr. Schmidt! It’s afternoon now!

Ah, you’re right! he smile. Tell your aunt sank you again. She’s a nice landlady. I will!

Seneca Village where my Auntie Eunice lives where her tenant Mr. Schmidt lives is Seventh avenue to Eighth, Eighty-second street to Eighty-ninth and some say higher. Mr. Schmidt lives in the house my auntie and uncle used to live in before they built the new one. Crost the field, I see Mr. O’Kelleher drivin a hog home. I wave. He wave back.

I run over to Colored School No. 3. My auntie at the front a the class nod her head to the back for me to sit, then she ask everybody, What’s one over two times five over six?

Everybody click click scratch their slates.

When dismission time come, my teacher-auntie and me walk back to her house hand-holdin. I tell her what Mr. Schmidt said to tell her he said.

It’s because I didn’t raise the rent. February first is Rent Day, to warn the tenants if the rent’s to be raised in May. If it’s too much, May first is Moving Day, but Mr. Schmidt won’t have to worry about that. Now why in the world would you be paying me a call on February ninth?

I grin. Look what Cathleen gimme!

What a pretty doll. You should leave it at home to play with so you don’t lose it.

I won’t! I can carry it around, not lose it!

All right, stubborn, don’t cry when it’s gone.

Won’t be gone!

Auntie Eunice cookin. We got her house all to ourself because Uncle Ambrose a seaman, more months away than home. Teachers ain’t sposed to be married but Auntie Eunice say she The Exception Proves The Rule and somethin else about bein a good convincer and childless. I look out the winda.

We in Seneca Village, Dolly, I tell my dolly. How the colored people come again? I ask my auntie.

Seneca Village as we know it began when land here was sold to a colored, then another colored, then another. In Seneca Village, the negroes are the landowners. But we get along fine with our tenants, those Johnny-come-latelys from across the Atlantic: the Irish and the German searching for America. Why don’t you read me some Thoreau.

I read Resistance to Civil Government while she stir the stew, then she wipe a tear and say, Your papa loved that book. Then she tell me read a little Winter’s Tale. I do, then: When you plan on going to school, Theo?

Which is a very often disagreement between me and my auntie. I say nothin. Auntie Eunice been teachin me to read since I was three. I tried school once for a week and didn’t care for it so didn’t go back. I know she know but I say nothin because impolite to insult somebody’s livelihood.

After supper, Auntie Eunice step outside with a bowl and no coat, come back in with a mound a freshly fell snow. Open a cupboard. Vanilla, sugar: vanilly snow!

For the birthday girl, she say and hand me a spoon.

I snuggle up with Auntie Eunice for the night. In the morn, she go to school, and I turn south, walkin ninety-six blocks back downtown to below First street. In the Thirties, a nativist man gawk at me: that look I sometime get from them ones claimin they the First Americans, descended from the original white people. Then he bark: Mongrel!

No! Mutt! I giggle and run.

Don’t let the ignorants worry you! my grammies and aunties always say. And between Seneca Village and my downtown home’s a whole lot a blocks a ignorance. Plenty a mutts where I live, home is black and Irish every day every minute crossin all kinds a paths, don’t the rest a the world only wish they got our harmony?

Near dinnertime, Park street bustlin in the pre-noon winter sun. Newsboys callin the afternoon editions—and there my grammies talkin together! Grammy Brook makin laundry deliveries, Grammy Cahill with her table set up peddlin anything she find to sell. Right now appears they dickerin on a shirt.

Grammies!

They see me, drop their haggle-faces to smile.

I take a hand a each one. Green eyes and flowy light-brown hair the Irish gimme, but my nose and lips took a bit a thickness from the colored. High yella, my skin betwixt: not rich dark like my father’s people nor rosy fair like my mother’s.

Long lashes just like your mammy, Grammy Cahill say.

Dimple-smile just like your papa, Grammy Brook say.

These I collect to make a picture, otherwise I don’t know what they looked like. My mother dies three days after I’m born, father two years after her. Last summer, couple nights I stayed with Nancy and Elijah the back alley. Their mother passed not long before and no rent money, now they sleep the street. I try cheerin em up: Look at the Milky Way! But I don’t speak a weather, rain and the comin snow. I don’t remind em beddin under the stars is fun n rare for me because any night a the week I got a choice of roofs: my colored grammy’s tenement or my Irish auntie’s boarding-house or my colored auntie’s uptown house or my Irish grammy’s tenement. Mutt I am: orphan lucky.

The grammies start up the bargainin again so I move on. Adventures await! And them bounteous in Five Points, Manhattan, New York City, when a birthday girl got a whole half-cent to squander on em.

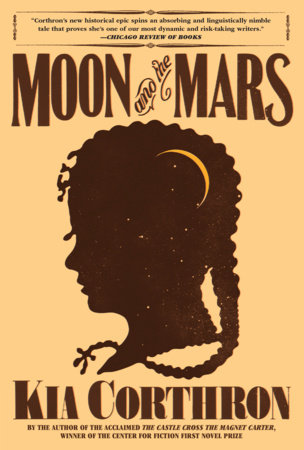

Copyright © 2023 by Kia Corthron. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.