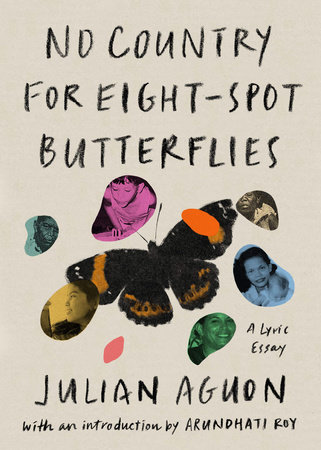

No Country for Eight-Spot Butterflies

IN GUAM, even the dead are dying.

As I write this, the US Department of Defense is ramping up the militarization of my homeland—part of its $8 billion scheme to relocate roughly 5,000 Marines from Okinawa to Guam. In fact, ground has already been broken along the island’s beautiful northern coastline for a massive firing range complex. The complex—consisting of five live-fire training ranges and support facilities—is being built

dangerously close to the island’s primary source of drinking water, the Northern Guam Lens Aquifer. Moreover, the complex is situated over several historically and culturally significant sites, including the remnants of ancient villages several thousands of years old, where our ancestors’ remains remain.

The construction of these firing ranges will entail the destruction of more than 1,000 acres of native limestone forest. These forests are unbearably beautiful, took millennia to evolve, and today function as essential habitat for several endangered endemic species, including a fruit bat, a flightless rail, and three species of tree snails—not to mention a swiftlet, a starling, and a slender-toed gecko. The largest of the five ranges, a 59-acre multipurpose machine-gun range, will be built a mere 100 feet from the last remaining reproductive håyon lågu tree in Guam.

If only superpowers were concerned with the stuff of lowercase earth—like forests and fresh water. If only they were curious about

the whisper and scurry of small lives. If only they were moved by beauty.

If only.

But the militarization of Guam is nothing if not proof that they are not so moved. In fact, the military buildup now underway is happening over the objections of thousands of the island’s residents. Many of these protestors, including myself, are Indigenous Chamorros whose ancestors endured five centuries of colonization and who see this most recent wave of unilateral action by the United States simply as the latest course in a long and steady diet of dispossession.

When the US Navy first released its highly technical

(and 11,000-page-long) Draft Environmental Impact Statement in November 2009, the people of Guam submitted over 10,000 comments outlining our concerns, many of us strenuously opposed to the military’s plans. We produced simplified educational materials on the anticipated adverse impacts of those plans, and provided community trainings on them. We took hundreds of people hiking through the jungles specifically slated for destruction. We took several others swimming in the harbor where the military proposed dredging some 40 acres of coral reef for the berthing of a nuclear-powered aircraft carrier. We testified so many times and in so many ways, in the streets and in the offices of elected officials. We

even filed a lawsuit under the National Environmental Pol-icy Act, effectively forcing the navy to conduct further environmental impact assessments, thus pushing the buildup back a few years.

But delay was all we won and the bulldozers are back witha vengeance.

A $78 million contract for the live-fire training range complex has been awarded to Black Construction, which has already begun clearing 89 acres of primary limestone forest and 110 acres of secondary limestone forest. It’s bitterly ironic that so many of these machines bear the name “Caterpillar” when the very thing they are destroying is that precious creature’s preciously singular habitat. To be sure, such forests house the host plants for the endemic Mariana eight-spot butterfly. But then again maybe a country that routinely prefers power over strength, and living over letting live, is no country for eight-spot butterflies.

While this wave of militarization should elicit our every outrage, indignation is not nearly enough to build a bridge.To anywhere. It’s useful, yes. But we need to get a hell of alot more serious about articulating alternatives if we hope to withstand the forces of predatory global capitalism and ultimately replace its ethos of extraction with one of ourown. In the case of my own people, an ethos of reciprocity.

And nowhere is that ethos more alive than in those very same forests—for it is there that our yo’åmte, or healers, are perpetuating our culture, in particular our traditional healing practices. It is there on the forest floor and in the crevices of the limestone rock that many of the plants needed to make our medicine grow. It is there that our medicine women gather the plants their mothers, and their mothers’ mothers, gathered before them.

These plants, combined with others harvested from elsewhere on the island, treat everything from anxiety to arthritis. As someone who suffers from regular bouts of bronchitis, I can attest to the fact that the medicine Auntie Frances Arriola Cabrera Meno makes to treat respiratory problems has proven more effective in my case than any medicine of the modern world. Yet Auntie Frances, like so many other yo’åmte I know, takes no credit for the cure. As she tells it, to do so would be hubris, as so many others are involved in the healing process: the plants themselves, with whom she con-verses in a secret language; her mother, who taught her how to identify which plants have which properties and also how and when to pick them; and the ancestors, who give her permission to enter the jungle and who, on occasion, favor her, allowing her to find everything she needs and more.

More than this, she tells me that I too am part of that process—that people like me, who seek out her services, give her life meaning. That she wouldn’t know what to do with herself if she wasn’t making medicine. That the life of a healer was always hers to have because she was born breech under anew moon and thus had the hands for healing.

But such things are inevitably lost in translation. And no military on earth is sensitive enough to perceive something as soft as the whisper of another worldview.

Earlier this month, I received an invitation to serve on the Global Advisory Council for Progressive International—a new and exciting global initiative to mobilize people around the world behind a shared vision of social justice.

So of course I said yes.

Truth be told, I know little by way of details—what kind of time commitment are we talking about? how will we work as a group? who else said yes?—but I am ready anyway. Ready to build a global justice movement that is anchored, at least in part, in the intellectual contributions of Indigenous peoples. Peoples who have a unique capacity to resist despair through connection to collective memory and who just might be our best hope to build a new world rooted in reciprocity and mutual respect—for the earth and for each other. The world we need. The world of our dreams.

The same world who, on a quiet day in September, bent down low and breathed in the ear of Arundhati Roy.

She is still on her way.

Copyright © 2022 by Julian Aguon. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.