My dad looked like crap.

His blond hair was flat and grubby, and his skin seemed too big for his bones. The muscly, tanned guy who’d built me a two-story tree house when I was a kid had been replaced by a pale shell of a man who didn’t build anything. You’d think it would be me who looked different. Dad said I didn’t. I couldn’t tell, since I didn’t cast a reflection anymore. But if I looked the same, then the face smiling out from the pictures on the walls of our house must still be my face: curly dark hair, round cheeks, brown skin like Mum’s, and blue eyes like Dad’s. Only I didn’t smile as much now.

Dad barely smiled at all.

He pressed his hand to his chest, out of breath from climbing up this rocky hill. There were a bunch of rock formations like this one around here, rising up from a flat red plain that was dotted with trees. I liked the trees. They were old and white and twisty, spiraling upward to fling out their leaves as if they were hoping to touch the sky. I liked the sky too; there seemed to be more of it here than in the city. There were no buildings to block it out. No big ones, anyway. We could see much of the town from where we stood: a sprawl of houses surrounded by the scattered trees, with a long river to the north. The town was covered in the same dust that coated everything, including our car and my dad’s rumpled shirt and pants. The dust hadn’t touched my clothes, of course. My dress would always be as yellow and crisp as it had been on the day Aunty Viv drove me to the birthday party.

Dad took a step closer to the edge of the hill, gazing outward.

“I don’t think you’re going to solve the case from up here,” I told him.

His gaze shifted in my direction. His eyes were bright with tears. Sometimes he couldn’t even look at me without sobbing. Today the tears didn’t fall. But I could hear them in his voice when he said, “I miss you, Beth.”

“I’m right here, Dad.”

Except we both knew I wasn’t. At least, not in the way he wanted me to be.

The accident had happened so fast. One minute I’d been sitting in Aunty Viv’s sedan, everything normal. Then I’d heard the four-wheel drive plowing through the bushes as it tore down the embankment. I’d looked up to see it hurtling at me, and . . . nothing.

I didn’t remember the actual dying part.

In fact, I felt as if I was still a living, breathing girl. Right now, for instance, I could see the town, hear the wind, smell the eucalyptus from the trees, and taste the gritty dust. I just couldn’t touch any of it.

This wasn’t how I’d imagined being dead, not that I’d ever spent much time thinking about it. But Mum had died when I was just a baby, and her two sisters—Aunty Viv and Aunty June—had always told me I’d see her again. Aunty June reckoned that Mum was “on another side.” Her husky voice echoed through my memory: This world’s got a lot of sides, like those crystals your Aunty Viv hangs in her window, and your mum’s just on a different side to us. So I’d always figured that when I passed over to another side, Mum would be there to meet me.

She hadn’t been. But I sometimes had a sense that she was waiting somewhere ahead—I’d be seeing her, I knew it. What I didn’t know was exactly when. The when didn’t matter so much, though, since I didn’t count minutes or hours anymore. Days began when the sun rose and ended when it set. In between, the connections I made—like the ways I helped my dad, or didn’t help him—were what told me if I was moving forward or backward. As my Grandpa Jim had once said to me, Life doesn’t move through time, Bethie. Time moves through life.

Dad was staring at me with the lost expression I’d come to hate. I waved encouragingly at the town. “Why don’t you go investigate?”

He stared for a moment longer. Then he turned away and wiped at his eyes, focusing his attention on the houses below us.

“I am investigating. I’m getting a sense of the place.” His voice was raspy. He drew in a deep breath, and added in a more even tone, “It reminds me of where your mum and I grew up.” His mouth twisted as if he’d tasted something bad. “Local police officers can have a lot of power in a place like this.”

He was thinking about his father. My grandpa on Dad’s side—who I’d never actually met—had been a cop for thirty years, and he wasn’t a good guy. Dad said his old man thought the law was there to protect some people and punish others. And Aboriginal people were the “others.”

Grandpa and Grandma Teller had thrown Dad out when he started seeing Mum, and they’d never wanted anything to do with me, their Aboriginal granddaughter.

“Do you think there are police like your dad in this town?” I asked.

“Maybe. Maybe not. Places like this are changing. Places everywhere are changing. Slowly, but it’s happening.” He sighed and shook his head. “I’m just not sure there’s anything here to investigate.”

I didn’t like the sound of that. I needed Dad to be interested in this case. My father was stuck in grief like a man caught in a muddy swamp. I had to get him to walk forward until he’d left the mire behind. Otherwise he’d just keep sinking until the water swallowed him.

“Someone did die in that fire,” I pointed out.

That was why Dad was here, because an inferno had engulfed a children’s home and killed . . . well, somebody. The body had been burned too badly to identify, so the cops were working on getting DNA or dental records to find out who it was. But at least it wasn’t one of the kids.

They’d all escaped, which I was glad about; the littlest was only ten, same age as my cousin Sophie.

“You can’t give up on this case before you even know who’s dead,” I told him.

“The only people living in that place besides the kids were the home’s director and the nurse. So it’s likely one of them,” Dad replied. “Probably the nurse, because he was tall, and so is our corpse.”

“Then what happened to the director?” I demanded. “There were no other bodies, so he can’t be dead. Which means he’s vanished. Very mysteriously.”

“The local police might have found him in the time it took us to drive here,” Dad said. “Don’t go overcomplicating this, Beth. The fire was likely accidental, remember.”

“You don’t know that for certain! The faulty wiring is only a . . . What did they call it? ‘Preliminary assessment’?”

Dad snorted. “Preliminary or not, the local cops could’ve handled all of this. At least until there was more information.” He gave a frustrated shake of his head. “I’ve only been sent here because of Oversight.”

Oversight was the name of an initiative the government had introduced after a series of bungled murder investigations. Whenever there was a possible homicide, an experienced senior detective had to look things over to make sure it was all being done right. Dad had lots to say about how the money put into Oversight should’ve been spent on more resources and better training instead.

Except Oversight wasn’t really why he was here. Dad’s boss, Rachel, thought Dad was still grieving and not ready for anything too difficult yet. I knew because I’d followed Dad around the police station and listened to what people were saying after he’d left a room. Rachel had figured she was doing him a favor by giving him an easy assignment. She was wrong. My father needed a real mystery. Something to solve. Something to do.

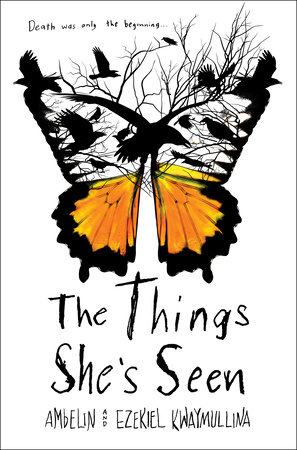

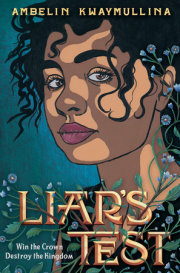

Copyright © 2019 by Ambelin and Ezekiel Kwaymullina. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.