One

It was still there, every time she opened the front door. It wasn’t real, she knew that, just her mind filling in the absence, bridging the gap. She heard it: dog claws skittering, rushing to welcome her home. But it wasn’t, it couldn’t be. It was just a memory, the ghost of a sound that had always been there.

“Pip, is that you?” her mom called from the kitchen.

“Hey,” Pip replied, dropping her bronze-colored backpack in the hall, textbooks thumping together inside.

Josh was in the living room, sitting on the floor two feet from the TV, fast-forwarding through the ads on the Disney Channel. “You’ll get square eyes,” Pip remarked as she walked by.

“You’ll get a square butt,” Josh snapped back with a snort. A terrible retort, objectively speaking, but he was quick for a ten-year-old.

“Hi, darling, how was school?” her mom asked, sipping from a flowery mug as Pip walked into the kitchen and settled on one of the stools at the counter.

“Fine. It was fine.” School was always fine now. Not good, not bad. Just fine. She pulled off her shoes, the leather unsticking from her feet and smacking against the tiles.

“Ugh,” her mom said. “Do you always have to leave your shoes in the kitchen?”

“Do you always have to catch me doing it?”

“Yes. I’m your mother,” she said, whacking Pip’s arm lightly with her new cookbook. “Oh, and, Pippa, I need to talk to you about something.”

The full name. So much meaning in that extra syllable.

“Am I in trouble?”

Her mom didn’t answer the question. “Flora Green called me today. You know she’s the new teaching assistant at Josh’s school?”

“Yes. . . .” Pip nodded for her mother to continue.

“Joshua got in trouble today, sent to the principal.” Her mom’s brow knitted. “Apparently Camilla Brown’s pencil sharpener went missing, and Josh decided to interrogate his classmates about it, finding evidence and drawing up a persons of interest list. He made four kids cry.”

“Oh,” Pip said, that pit opening up in her stomach again. Yes, she was in trouble. “OK, OK. Should I talk to him?”

“Yes, I think you should. Now,” her mom said, raising her mug and taking a noisy sip.

Pip slid off the stool with a gritted smile and padded back toward the living room.

“Josh,” she said lightly, sitting on the floor beside him. She muted the television.

“Hey!”

Pip ignored him. “So, I heard what happened at school today.”

“Oh yeah. There’s two main suspects.” He turned to her, his brown eyes lighting up. “Maybe you can help--”

“Josh, listen to me,” Pip said, tucking her dark hair behind her ears. “Being a detective is not all it’s cracked up to be. In fact . . . it’s a pretty bad thing to be.”

“But I--”

“Just listen, OK? Being a detective makes the people around you unhappy. Makes you unhappy . . . ,” she said, her voice withering away until she cleared her throat and pulled it back. “Remember Dad told you what happened to Barney, why he got hurt?”

Josh nodded, his eyes growing wide and sad.

“That’s what happens when you’re a detective. The people around you get hurt. And you hurt people, without meaning to. You have to keep secrets you’re not sure you should. That’s why I don’t do it anymore, and you shouldn’t either.” The words dropped right into that waiting pit in her gut, where they belonged. “Do you understand?”

“Yes . . .” He nodded, holding on to the s as it grew into the next word. “Sorry.”

“Don’t be silly.” She smiled, folding him into a quick hug. “You have nothing to be sorry for. So no more playing detective?”

“Nope, promise.”

Well, that had been easy.

“Done,” Pip said, back in the kitchen. “I guess the missing pencil sharpener will forever remain a mystery.”

“Ah, maybe not,” her mom said with a barely concealed smile. “I bet it was that Alex Davis, the little shit.”

Pip snorted.

Her mom kicked Pip’s shoes out of her way. “So, have you heard from Ravi yet?”

“Yeah.” Pip pulled out her phone. “He said they finished about fifteen minutes ago. He’ll be over to record soon.”

“OK. How was today?”

“He said it was rough. I wish I could be there.” Pip leaned against the counter, dropping her chin onto her knuckles.

“You know you can’t, you have school,” her mom said. It wasn’t a discussion she was prepared to have again; Pip knew that. “And didn’t you have enough after Tuesday? I know I did.”

Tuesday, the first day of the trial at New Haven Superior Court, Pip had been called as a witness for the prosecution. Dressed in a new suit and a white shirt, trying to keep her hands from fidgeting so the jury wouldn’t see. Sweat prickling down her back. And every second, she’d felt his eyes on her from the defendant’s table, his gaze a physical thing, crawling over her exposed skin. Max Hastings.

The one time she glanced at him, she’d seen the smirk behind his eyes that no one else would see. Not behind those fake, clear-lens glasses, anyway. How dare he? How dare he stand up and plead not guilty when they both knew the truth? She had a recording, a phone conversation with Max admitting to drugging and raping Becca Bell. It was all right there. Max had confessed when Pip threatened to tell everyone his secrets: the hit-and-run and Sal’s alibi. But it hadn’t mattered anyway; the private recording was inadmissible in court. The prosecution had to settle for Pip’s recounting of the conversation instead. Which she’d done, word for word . . . well, apart from the beginning, of course, and those same secrets she had to keep to protect Naomi Ward.

“Yeah, it was horrible,” Pip said, “but I should still be there.” She should; she’d promised to follow this story to all of its ends. But instead, Ravi would be there every day in the public gallery, taking notes for her. Because school wasn’t optional: so said her mom and the new principal.

“Pip, please,” her mom said in that warning voice. “This week is difficult enough as it is. And with the memorial tomorrow too. What a week.”

“Yep,” Pip agreed with a sigh.

“You OK?” Her mom paused, resting a hand on Pip’s shoulder.

“Yeah. I’m always OK.”

Her mom didn’t quite believe her, she could tell. But it didn’t matter because a moment later, there was a knock on the front door: Ravi’s distinctive pattern. Long-short-long. And Pip’s heart picked up to match it, as it always did.

File Name:

A Good Girl’s Guide to Murder: The Trial of Max Hastings (update 3).wav

[Jingle plays]

Pip: Hello, Pip Fitz-Amobi here and welcome back to A Good Girl’s Guide to Murder: The Trial of Max Hastings. This is the third update, so if you haven’t yet heard the first two mini-episodes, please go back and listen to those first. We are going to cover what happened today, the third day of Max Hastings’s trial, and joining me is Ravi Singh . . .

Ravi: Hello.

Pip: . . . who has been watching the trial unfold from the public gallery. Today started with the testimony from another of the victims, Natalie da Silva. You may well recognize the name; Nat was involved in my investigation into the Andie Bell case. I learned that Andie had bullied Nat at school, and had even sought and distributed indecent images of her on social media. I believed it could be a possible motive and, for a while, I considered Nat a person of interest. I was entirely wrong, of course. Today, Nat appeared in New Haven Superior Court to give evidence about how, on February 21, 2014, she was allegedly drugged and sexually assaulted by Max Hastings at a calamity party. But as I’ve explained before, due to Connecticut’s ridiculous statute of limitations, Max cannot be charged for either rape or sexual assault because the alleged offenses happened more than five years ago in the cases of both Nat da Silva and Becca Bell. For these two victims, Max is instead being charged with kidnapping in the first degree, as the state has no statute of limitations for that crime. In Connecticut, the definition of kidnapping includes restraining someone with intent to inflict physical injury or sexual abuse and therefore the state attorney general recommended these charges instead. Of course, the whole thing is disgraceful, but I won’t start on my feelings about the statute of limitations again. I think I’ve previously made those very clear. So, Ravi, can you take us through how Nat’s testimony went?

Ravi: Yeah. So the prosecutor asked Nat to establish a timeline of that evening: when she arrived at the party, the last instance she looked at the time before she began to feel incapacitated, what time she woke up in the morning and left the house. Nat said she has only a few hazy snatches of memory: someone leading her into the back room, away from the party, and laying her down on a sofa; her feeling paralyzed, unable to move, and then of someone lying down beside her. Other than that, she described herself as being blacked out. And then, when she woke up the next morning, she felt awful and dizzy, like it was the worst hangover she’d ever had. Her clothes were in disarray and her underwear had been removed.

Pip: And, to revisit what the prosecution’s expert witness said on Tuesday about the effects of benzodiazepines like Rohypnol, Nat’s testimony is very much in line with what you’d expect. The drug acts like a sedative and can have a depressant effect on the body’s central nervous system, which explains Nat’s feeling of being paralyzed. It feels almost like you’re separated from your own body, like it just won’t listen to you, your limbs aren’t connected anymore.

Ravi: Right, and the prosecutor also made sure the expert witness repeated, several times, that a side effect of Rohypnol was “blacking out,” as Nat said, or having anterograde amnesia, which means an inability to create new memories. I think the prosecutor wants to keep reminding the jury of this point because it will play a significant part in the testimonies of all the victims, the fact that they don’t remember exactly what happened because the drug affected their ability to make memories.

Pip: The prosecutor also repeated that fact regarding Becca Bell. As a reminder, Becca recently changed her plea to guilty, despite a defense team who were confident that they could get her no jail time due to her being a minor at the time of Andie’s death, and the circumstances surrounding it. She accepted a four-year sentence, suspended after eighteen months, followed by two years’ probation. Yesterday, Becca testified by video link from prison, where she will be for the next year and a half.

Ravi: Exactly. And like with Becca, today the prosecution was eager to establish that Nat had only one or two alcoholic drinks the night of the alleged attacks, which couldn’t possibly account for her level of intoxication. Specifically, Nat said she only drank one bottle of beer that night. And she stated who allegedly gave her that drink on her arrival: Max.

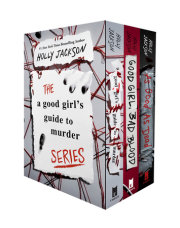

Copyright © 2021 by Holly Jackson. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.