I. Love

1.

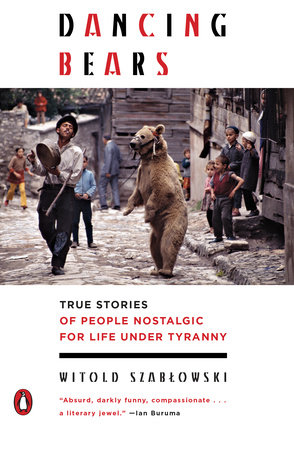

Gyorgy Marinov hides his face in his right hand, and with his left taps the ash from his cigarette onto the ground, which in the village of Dryanovets is a deep-brown color that passes here and there into black. We're sitting outside his house, which is coated in gray plaster. Marinov is a little over seventy, but he's not bent double yet, although in Dryanovets, a village in northern Bulgaria inhabited mainly by Gypsies, very few men live to his age.

It's not much better for the women either. There's a death notice pinned to the door frame of Marinov's house with a picture of a woman only a little younger than he is. It's his wife-she died last year.

If you go through that door, passing a cart, a mule, and a heap of junk along the way, you come to a dirt floor. In the middle of the room there's a metal pole stuck into the ground. A female bear called Vela spent almost twenty years tied to it.

"I loved her as if she were my own daughter," says Marinov, as he casts his mind back to those mornings on the Black Sea when he and Vela, dependent on each other, pointed their noses in the direction of the water, had a quick bite of bread, and then set off to work along the road as the asphalt rapidly heated up. And those memories make him melt, just as the sunshine would melt the asphalt in those days, and he forgets about his cigarette until the lighted tip starts to burn his fingers; then he tosses the butt onto the brown-and-black earth, and he's back in Dryanovets, outside his gray house with the death notice pinned to the door frame.

"As God is my witness, I loved her as if she were human," he says, shaking his head. "I loved her like one of my immediate family. She always had more than enough bread. The best alcohol. Strawberries. Chocolate. Candy bars. I'd have carried her on my back if I only could. So if you say I beat her, or that she had a bad time with me, you're lying."

2.

Vela first appeared at the Marinovs' house at the beginning of the gloomy 1990s, when Communism collapsed, and in its wake the collective farms, known in Bulgaria as TKZS-trudovo kooperativno zemedelsko stopanstvo, or "labor cooperative farms"-began to go under. "I was a tractor driver at the TKZS in Dryanovets. I drove a Belarus tractor and I loved my job," says Marinov. "If I could have, I'd have worked at the collective farm to the end of my days. Nice people. The work was tough sometimes, but it was in the open air. We never lacked a thing."

But in 1991 the TKZS began to slow down. The manager called Marinov in and told him that under capitalism a tractor driver must not only drive a tractor but also help with the cows, and the sowing, and the harvest. Marinov had helped people to do other jobs on very many occasions anyway, so he couldn't see any problem. The manager replied that he understood all that, but that even if his tractor drivers were multifunctional, he couldn't keep twelve of them on under capitalism-because until then there had been twelve at the TKZS in Dryanovets. At most, he could keep three. Marinov was made redundant.

"I was given three months' pay in advance-then that was it, good-bye," he recalls, and adds: "If you go out of my house, walk a short way to the right, and stand on the hillock, you'll see what's left of our collective farm. It was a beautiful farm, three hundred cows, a thousand acres, extremely well run! Most of the people working there were Gypsies, because the work was too stinky for Bulgarians. Now it has all fallen through, and instead of working, the Gypsies sit around unemployed. But the milk they sell in the market at Razgrad is German. Clearly it's worth it for the Germans to have big farms but not for the Bulgarians."

In 1991 Marinov had to ask himself the basic question that every redundant worker has to face: "What else am I capable of doing?"

"In my case the answer was simple," he says. "I knew how to train bears to dance."

His father and grandfather were bear keepers, and his brother, Stefan, had kept bears ever since leaving school. "I was the only one in the family who'd gone to work at the collective farm," says Marinov. "I wanted to try another life, because I already knew about bears. Lots of bear keepers got jobs at the farm, as I did. But I grew up around bears. I knew all the songs, all the tricks, all the stories. I use to bottle-feed my father's two bears by hand. When my son was born, he and the bears were kept together. There were plenty of times when I got it wrong-my baby drank from the bear's bottle, and the bear from his. So when they fired me from the collective farm, there was one thing I knew for sure: if I wanted to go on living, I had to find a bear as fast as possible. Without a bear, I wouldn't survive a year.

"How did I find one? Wait, let me light another cigarette and then I'll tell you the whole story."

3.

"I went to the Kormisosh nature reserve to get a bear. It's a well-known hunting ground; apparently Brezhnev forgave our Communists a billion leva of debt in exchange for taking him hunting there. So I was told by a guy who worked at Kormisosh for forty years, but I don't know if it's true.

"First I had to go to Sofia, to the ministry responsible for the forests, because I had a friend there from school. Thanks to him, I got a voucher for a bear, authorizing me to buy one at Kormisosh, so from Sofia I went straight to the reserve. They knew of me there by hearsay, because my brother, Stefan, had been to them in the past with other bear keepers, and in those days he'd been a real star. He used to perform at a very expensive restaurant on the Black Sea, where the top Communist Party leaders used to go. He was on television several times. Lots of people all over Bulgaria would recognize him.

"Stefan got his bear from a zoo in Sofia. A drunken soldier had broken into the bear enclosure, and the mother happened to have cubs at the time, so she attacked him and killed him on the spot. They had to euthanize her, as they always do if a zoo animal kills someone. Stefan heard about it and went to buy one of the cubs.

"At the restaurant show, first came some girls who danced on hot coals, and then he was on. He'd start by wrestling with the bear and end with the bear massaging the restaurant manager's back.

"Then a long line of people would form, to have the bear massage them too. My brother earned pretty good money that way. Of course he had to share it with the manager, but there was enough for both of them.

"So I went to Kormisosh. The forester asked me to pass on his greetings to my brother, and then they brought out the little bear. She was a few months old. They're best like that, because they're not too attached to their mothers yet-they can still change keepers without making a fuss. If you take an older bear away from its mother, it can starve itself to death.

"So she's looking at me. And I'm looking at her. I'm thinking, 'Will she come to me or not?' I kneel down, hold out my hand, and call, 'Come here, little one.' She doesn't move, just gazes at me, and her eyes are like two black coals. You'd fall in love with those eyes-I tell you.

"I took a piece of bread out of my pocket, put it in the cage, and waited for her to go inside. Again she looked at me. She hesitated for a moment, but then she went in. 'Now you're mine,' I thought, 'for better or worse.' Because I was fully aware that a bear can live with someone for thirty years. That's half a lifetime!

"I paid thirty-five hundred leva for her, but I didn't regret a single penny. She went straight to my heart at once. That money was my payoff from the collective farm, plus a little more that I'd borrowed. In those days you could buy a Moskvich car for about four thousand.

"But I couldn't afford a Moskvich as well, so I went part of the way home with the cub by bus, which was an immediate pleasure, because all the children were interested in my bear and wanted to pet her. I took it as a good sign. And it showed I'd gotten a really great bear, friendly and lovable. And then I thought, 'Your name will be Valentina. You're a beautiful bear, and that's a beautiful name, just right for you.' And it stuck. Valentina, or Vela for short.

"Then we had to transfer to a train, and Vela traveled in the luggage compartment. The conductor didn't want a ticket for her; he just asked me to let him pet her. Of course I did. But I also insisted on paying for a ticket. That's what I'm like-if you owe something, you have to pay, and that's final. I always used to buy Vela a ticket, like for an adult person, without any discount for petting her. There was just one occasion when the conductor insisted. He said someone in his family was in the hospital, and he regarded the bear as a good sign, as good luck for that person. I could see it mattered to him, so that one time I didn't pay up."

4.

"The biggest problem I had was with my wife. Because I went to Kormisosh without telling her. And when I suddenly appeared at the front door with a bear, she went crazy.

"'Are you out of your mind? What sort of a life are we going to have?' she screamed, and came at me with her fists flying. I gave in to her, and left the house.

"I'd always done my best to live in harmony with my wife, and I can't say I wasn't upset at her for screaming like that, but I did understand her to some extent. The life of a bear keeper isn't easy. Of course, he can earn a living. You see this house? It's still standing thanks to our Valentina. On a good day at the seaside I earned more than I did in a whole month at the collective farm.

"But it's a job that has its price. You have be on the alert the whole time to make sure the bear doesn't go wild and harm you-Vela was with us for twenty years, but you could never drop your guard for an instant. You don't know when your bear's instincts might awaken. A man I know in the next village, Ivan Mitev, had had his bear for fifteen years. He bought her at the circus, so you might think he'd never have any trouble with her-her mother and grandmother had never known freedom, so her instincts should have been well suppressed. Until one day Ivan failed to tie her up properly, and she broke loose, killed three hens, and ate them. How she did it, I don't know. Vela sometimes had hens flapping around her head while she slept, but it never occurred to her to eat them. But it happened with Mitev's bear. Once her instincts had awoken, she started attacking people-the keeper, his wife, and their children. She kept trying to bite them. Suddenly they had a major problem. Unfortunately, a bear has no sense of gratitude and won't remember that you've fed it corn and potatoes for the past fifteen years. If it goes wild, it'll start to bite.

"On top of that, bear keepers aren't exactly welcome among people. We're not respected. I had a problem with this for ages, and I never, ever performed with Vela either here, in Dryanovets, or in the neighboring villages. Only when I reached Shumen, and that's almost forty miles away from us, would I take out my gadulka, or fiddle, and start to work.

"So when I brought the little bear cub home, my wife knew perfectly well how it would all end. Women are very wise, and the moment she saw that shaggy little creature she also saw the people who'd laugh at us, the nights we'd spend out in the rain, and us trailing from yard to yard in the hope that someone would toss us a few pennies.

"But I knew my dearly departed wife, as well. And I knew that if I put up with her outburst of anger, she'd soon come to love the bear like her own child.

"I wasn't mistaken. By the time the first winter came, she was urging me to make Vela a shelter as soon as possible or the animal would freeze. And whenever it rained, she took an umbrella and ran to the tree where Vela was tied up, to make sure the little bear didn't get wet. If she could have, she'd have kept her in the house, the way some city folk keep dogs."

5.

"When I brought the cub here, the worst trouble I had was from a major in the militia-or had it been renamed the police by then? I can't remember-those changes happened so quickly that no one could keep up with them. When he found out I had a bear cub, he came and said, 'Citizen Marinov, I've heard you're keeping a bear at your place. I'll give you seven days to get rid of it.'

"I tried arguing, saying, 'But Mr. Major, what do you mean? I bought it legally. I have a receipt from the Kormisosh park. Anyway, thanks to your economic transformation they've taken away my job, so let me do something else!'

"But the major refused to listen. 'You've got seven days,' he said. 'And that's my last word on the matter, Citizen Marinov.'

"It was suspicious, because there were six other bears in our village at the time, including the one belonging to my brother, Stefan. So why was he picking on me? I don't know. Maybe he'd had enough of the bears. Or maybe he wanted a bribe. I didn't bother to ask. It was all legally aboveboard, so there was no reason for me to give him anything. I went to Shumen, to see the people who represent the Ministry of Culture, and I asked them to call Sofia at my expense, and there they confirmed that I had all the necessary documents. You couldn't keep a bear illegally. A vet had to examine it, and the Ministry of Culture had to confirm that my program would be of high artistic quality. The ministry confirmed that I had all the papers, in Razgrad they issued me an extra bit of paper, and the militia major was told to leave me in peace.

Copyright © 2018 by Witold Szablowski. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.