The First StepThunder

banging on the door.

Voices yelling—

like lightning.

But—

Daddy already left for work.

A loud crack tells me

the door to outside is wide open.

Light pours in.

Visitors Who is here? I dash to the edge of the stairs to see.

“Lacey,” says Mama, running up. “Get ready. We have

to go now.”

I freeze.

“Your grandparents are here to help us leave.”

Leave?

We’re not supposed to go anywhere.

We’re not supposed to leave!

We never leave home without Daddy.

“Now!” Mama tosses a bag to me.

“Put on your shoes!”

My little sister screams, curling her toes.

Jenna won’t let Mama put on her shoes.

She knows the rules too.

Shoes mean going out—

and we cannot go out without Daddy.

“You didn’t tell me we were leaving!” I scream.

Mama replies, “I couldn’t—

it wasn’t safe then.”

Invasion Tall men in black boots come up the stairs.

Footsteps like a storm.

THUD!

CRASH!

CRACK!

Their metal badges shine even in our dim room,

where dark-brown fabric is pinned over the windows

to keep out the light, the way Daddy wants it.

I stare—at them, at their guns.

Daddy wears his on a sling, or leaves it in the fruit bowl,

and he yells at us if we touch it.

“You have five minutes,” one of them warns.

As quick as I can, I cram things into the bag,

but it’s not easy with shaking hands.

Suddenly, my grandmother comes upstairs,

rushing past the men to give Mama a hug.

But Mémère isn’t supposed to be here!

Daddy says she’s not allowed.

If Daddy comes back now—

The thought fills me with fear.

My face feels cold; my feet won’t move.

I’m planted here, like a tree.

Mama reaches for my hand.

“It’s okay,” she says, looking into my eyes.

“We’re going to be okay.”

Rules Daddy has many rules,

but Mama has rules too.

We just have to do exactly what Daddy says—

stay quiet, stay inside,

and if he wants to play,

play along.

If we follow these rules,

everything will be fine.

Leaving breaks Mama’s most important rule

about how to stay safe.

Mama changed the rules and didn’t tell me.

Saving Some Things “Stick them onto what you want to bring,” Mémère says,

handing us each a small stack of bright-pink paper squares.

I mark the framed pictures of our baby feet,

Jenna’s blanket and blocks, my little deer I named Diamond,

my drawings, Mama’s paintings, boxes stacked in a corner.

Then I remember my nature journal.

I find it tucked under my mattress,

where I hid it from Daddy.

Instead of tagging it, I place it in my bag.

But where’s Mac?

I look around the room for our dog.

“Mac!” I call out over and over again.

Now! “There’s no time for that! We have to

get you out before he comes back,”

the tall men roar as loud as Daddy.

I cover my ears with my hands.

Other men rush by, taking out boxes and boxes.

Daddy’s long guns. Daddy’s short guns.

They are even dropping boxes out the windows

that Daddy always kept closed.

Where are they taking everything? And us?

“Let’s go!” “NOW!” Their voices boom over Jenna’s crying.

Even though my head is spinning,

somehow I make it downstairs without falling.

Pépère meets me at the bottom.

“Okay, let’s go, kiddo,” he says.

Muddy boots have stomped

all over the thunderstorm drawings

that I was making with Jenna

on the kitchen floor this morning.

Our drawings, stomped over.

Leaving “Mac!”

Our dog appears out of nowhere.

He runs to me, shaking, tail tucked in,

and I stick a pink paper square on him.

Daddy says Mac is his, but Daddy is mean to him.

Mac whimpers while I rub his soft head.

“Don’t worry, bud. You’re coming with me.”

We walk toward the open door together.

The bright sunlight hurts my eyes,

making it hard to see.

I hold on to Mac with one hand

and Mama with the other

as we step outside, down the broken steps

that Daddy never fixed.

Our feet slop across the mud in our yard.

That means it’s springtime in Maine.

The driveway is full of muddy tire tracks.

Daddy will notice that.

He’s going to be so mad that people were here

while he was gone.

In the Driveway Pépère opens his car door for me.

White teddy bears are on the seats.

“What about Jenna’s car seat?” I ask.

“She has a new car seat,” he says.

“Daddy’s going to be so mad,” I say.

“It’s okay,” Mama says as she buckles Jenna in.

“Don’t worry about what Daddy will think.”

But what Daddy thinks

is what we

always worry about.

I take a step into the car and turn to help Mac up,

but a man outside the car puts his hand through Mac’s collar,

holding him back.

“He can’t go with you now,” he says, pulling Mac away.

“We have to get you to safety first.”

“No!” I scream as he shuts the car door.

“Mac!”

My heart twists.

“Mama!” I plead, looking at her.

Her eyes fill, but she says nothing,

wrapping her arm around me.

I stare through the window at Mac.

He’s trying to wiggle away.

We drive off with white teddy bears on our laps

onto a road we’ve never been on without Daddy.

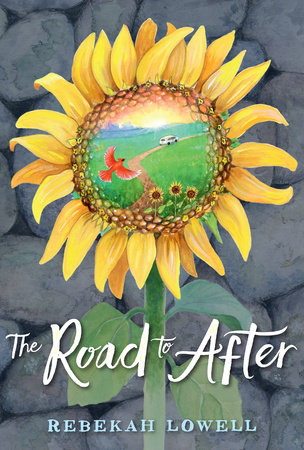

Copyright © 2022 by Rebekah Lowell. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.