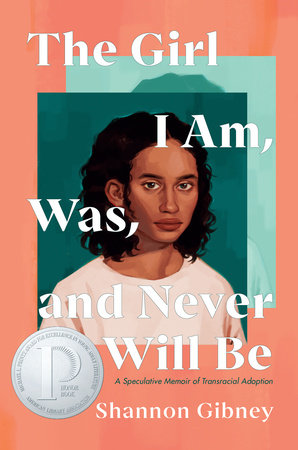

Books for Black History Month

In honor of Black History Month this February, we are highlighting essential fiction and nonfiction for students, teachers, and parents to share and discuss this month and beyond. Join Penguin Random House Education in celebrating the contributions of Black authors and illustrators by exploring the titles here: BLACK HISTORY – MIDDLE SCHOOL BLACK HISTORY –