Introduction In June 2015, I was given the life-changing opportunity to pitch a story to Catherine Burns, artistic director of The Moth. As a long-time fan and audience member, I was thrilled—and terrified. I often listened to Moth stories to be transported out of my own life, and to be transformed by the entertaining, deeply moving, and amazing lives of others. Now The Moth was calling me! Did I even have a story to tell?

Adrenaline (born of excitement and fear) surged through my veins. This was a chance to hone my own storytelling craft with experts, and maybe even to be heard by Moth audiences all around the world.

Storytelling lies at the heart of my professional life. As a professor of critical media studies, much of my teaching involves finding stories that can transform abstract concepts and history into relat able and compelling experiences. As an organizer striving to make institutions more equitable, effective storytelling can not only dismantle false narratives but also cut through intractable political divides to reveal how power is currently working, how we got here, and what needs to be done. As a journalist, great stories are the beating heart of impactful reporting, essays, and narrative-nonfiction audio productions.

For all of these reasons, I enthusiastically accepted the invitation. But as soon as I hung up, I felt a fluttering of fear in my chest. My own stories had made friends and family laugh, but they were really just short anecdotes told to people who were being generous. To make matters worse, my experience as a hip-hop artist had taught me that there’s a big difference between telling a funny story to a couple of friends and telling it to hundreds or thousands of strangers. On stage, everything but the power of your story is stripped away, and it is very easy to fall flat. The few times this happened to me, it felt like nothing could remove the stench of doom from the air.

After an hour, the fluttering in my chest turned into panic. Every time I tried to summon a potential story from my past, a crowd of critical voices in my head would quickly impale it with a flurry of criticism: N

o one cares about this. Get over yourself. You’ve never saved a life. Why do you get to stand in front of people and talk about your weird silly stuff? Jay Allison, the longtime producer of The Moth Radio Hour, had introduced me to the Moth team, and I reached out to him to explain my predicament. Jay told me, “Well, Chenjerai, Moth stories can be deeply inspirational, but they’re very different from the exclusively heroic or positive tales that some other places invite you to tell. I don’t know where you’ll end, but as a place to start, remember that everyone is entertained by, and relates to, a train wreck. Stories about failure and learning can be powerful.”

Failure! That was something I had a lot of. I could definitely remember and tell a story about that.

Up until this point in my life, I had presented myself, and been taken seriously, as a scholar, organizer, journalist, and hip-hop artist. Stories about the confusing, awkward, and downright embarrassing parts of my life, and the lessons that might be learned from them, had been pushed to the margins of my mind. They would spill out, poorly developed, at family dinners or on dates, or in the classroom. My friends and family and students welcomed the best parts of these stories and tolerated the rest.

The pounding in my chest calmed enough for me to start reflecting and jotting down some notes. My best bet was a story about some funny and painful moments in my career as a hip-hop artist.

By the time my group, the Spooks, finished our last tour in 2005, we had earned gold singles in three countries and a gold album in the UK, and had performed in front of more than a million people. After my music career slowed down, I was forced to learn new skills, figure out new ways to sustain myself, and forge a new identity—but I never really processed or properly mourned this tumultuous shift in my circumstances.

When I was ready, I called Catherine, and she listened closely and supportively as I ran through several story possibilities. Breathlessly, I shared the story of meeting Laurence Fishburne

on my own music video set as the Spooks were taking off. But I took forever to get to the main point, losing the thread several times along the way. Another anecdote involved me botching an Excel sheet at a temp job. It was meant to illustrate the tragicomedy of my post-fame life, but I stretched it out far too long and included a wealth of irrelevant details. I also told Catherine about meeting Laurence Fishburne for the second time, while working as a security guard at a film festival. But this time I had hidden from him, ashamed of my humbled station in life (and my JCPenney suit). It was a meandering, sloppy affair with a sad, deflating ending.

After listening closely, Catherine recognized the seeds of a story—something that had elements of humor, tragedy, and drama, and would likely resonate with a lot of people. I use the term seeds because clearly my story wasn’t developed yet. When I first shared my story, I thought that having been famous—and then not—was the point of the story, and that meeting Fishburne twice was the punchline. I thought the ending of the story was me in my humiliated state. None of those initial instincts was correct.

The lack of an ending was crucial. Laughing with me, Catherine pointed this out by saying, “Wow, that second time you saw Laurence feels so awkward and terrible. But I feel like that’s not the ending. I mean, you seem to be doing much better now. What happened?” When she asked this, something emotional and planetary moved inside of me. I didn’t know what happened. I didn’t have an ending because, even though my life had moved forward, some part of Chenjerai was still standing there in that JCPenney suit, feeling defeated and small.

A day or so before the live show, the storytellers meet and share their stories for final notes and tweaks. This is a scary but ultimately beautiful part of The Moth’s process.

I will never forget my first rehearsal. The day before, I was attending a protest in South Carolina. The rehearsal was going to be in person at The Moth’s offices. This meant that I had to drive from Clemson to New York. The good news was that the twelve-hour drive gave me plenty of time to rehearse my story. But it also allowed time for doubt to creep in. Was I really driving to another state to tell a story in front of one thousand people? With no music? Because one person in New York told me that this story is interesting? Maybe I needed to tell a more political story. After all, I was not here to simply entertain people. I became so filled with doubt and confusion that I called Catherine and proposed telling a different story. Catherine listened and was fully open to this. But her questions helped me realize that if I was going to tell a political story, I should put the same time and effort into it that I had put into this one. I think she also understood that my sudden passion for this new idea was a by-product of second-guessing the story I was currently planning to tell.

By the time I arrived in New York, I was back to telling story number one. But my doubt returned when other storytellers started confidently weaving their own tales at rehearsal. This anxiety didn’t last long, however. Moth listeners have a special way of holding storytellers up by laughing at what’s funny, “wow”-ing at what is genuinely shocking, nodding in validating affirmation, and even shedding tears when moved. As soon as I shared my first punchline, the room laughed, and I felt better. Relief flooded my body and I felt that I was hanging out with friends—that we were all going to make each other stronger and support each other through the process. My point here is that the horrifying feeling of pressure was necessary, because by the time I got to the big stage, I had already faced my fears.

As I got closer to the show, I remembered a turning point in my story. I was applying for a new temp job, feeling defeated, wearing the same JCPenney suit, when I heard a Spooks song playing and I saw people in the temp office enjoying it. This reminded me that the power of my music wasn’t contingent on my own fame or hanging with celebrities. It was about the joy of dreaming up and shaping my art. The office workers were enjoying what I had made, and they reminded me of the power and joy I had felt creating it.

In the final scene of my story, I talked about sharing a lesson with my students: Follow your passions, but be prepared to brace for impact. And after going to sleep thinking hard about the core message of my story, I woke up with the line “Sometimes you have to figure out who you’re not before you can become who you are.”

When I tried this line at the rehearsal, I felt the swell of recognition and affirmation wash over the room. Catherine nodded confidently in a way she hadn’t before and said, “Yes! That’s it. That’s the ending.”

The Moth team lovingly pushed me toward a stronger ending—the real ending—and helped me recognize when I had found it.

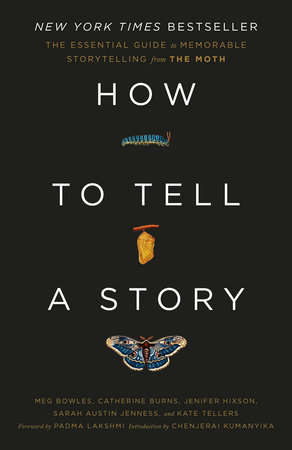

Copyright © 2022 by Meg Bowles, Catherine Burns, Jenifer Hixson, Sarah Austin Jenness, and Kate Tellers; foreword by Padma Lakshmi; introduction by Chenjerai Kumanyika. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.