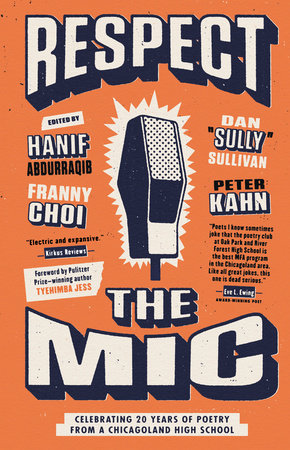

FOREWORD

When I first opened the pages of Respect the Mic, I couldn’t help but reflect on the many classrooms, community centers, and prisons that I had the privilege of teaching in during my years in Chicago, a place I grew up in for eighteen years, growing through stumbles and starts into where I am today, eighteen years later (!), still stumbling and starting my way through line after line after line of poetry. It was in those classrooms—the Gallery 37 spaces, open mics, slams, HotHouse, Guild Complex, Young Chicago Authors, Oak Park and River Forest High School [OPRFHS], Green Mill, Spices, and many other spaces—that I was able to better hear how to put the world on the page. Letter by letter, the streets and alleys, the bitter-cold winters and blazing summers wrote their poems into me with the asphalt and blues bars singing their sweltered up names onto mine.

When you read these poems, you will no doubt hear the true voice of Chicagoland for yourself, the collusion of city and suburb, alley and lawn, that make up the capital of the Midwest. You will hear echoes of the great brawling, butchering, kitchenette-historied, Gold Coast–glittered blues town. You’ll feel the bass line of house music, the thrum of trap, the chorus of Cumbia. The great thing about coming of age as a writer in Chicago is that you have a skyscrapered, schoolyarded, L train–tracked electricity in each space you sprawl into—a checkerboard of ethnicities to navigate and explore all the American tongues. In Chicagoland, poets inhabit the XY axes of gridded streets to teach you that if the poem is gonna be worth it, it better sneak sweat-close to your skin and snatch off your chains. It better out-howl the Hawkish wind pushing down Michigan Avenue midwinters. It better be as scrawny-legged graceful as the grade-school hoopers in the park after dark. It better grin lopsided with a gold-toothed glint before it spits out a trochee or an iamb.

OPRFHS has been an intrepid safe house for poetry over the past three decades. It is home to a cadre of extraordinary teachers with an extraordinary interest in bringing poets from all over the country to their auditorium, filling the stage with verse after verse, book after book, in front of a packed audience of young listeners entranced with the power of The Word.

On that stage, and in these pages, you will also hear how a poet “can’t wait for the day where I find out who I wanna be . . .” you will understand even further why “she was the only one brave enough / to say it out loud.” You’ll hear bullets in bucket hats, an opus of bucket drums, and a baile on a Friday night. This collection is a bit of a reunion—a calling of voices that have been shaped and billowed and baked in the sun of each other’s voices, each other’s shouts in the hallways and classrooms of this Respect for The Mic. ’Cause that is what it boils down to in the end. Respect. That’s all we really have left, and when it’s done right, that’s all you really need to lean on. This OPRFHS literary tradition is a luscious, living, lie-killing, life-dealing part of doing it right. Inclusive, expansive, and digging into the well of American identity in all its myriad possibilities toward a More Human World. Drinking from the heart of the heart of a city that’s got a Mississippi train track querying through its Music:

What city were you born in? A conditional war zone—a consequence of blessings.

I digress. The point is that this is supposed to be a foreword. But once you in it, you be all the way in it. And that’s all the forward you need to make it back Home again. You’ll see what I mean. You’ll hear it, too, those voices in the hall . . .

In conclusion, I leave you with two phrase poems I learned in Chicago: the salutations of Kwame Nkrumah and the mighty Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians . . .

Forward Ever, Backward Never! *** Ancient to the Future!

—Tyehimba Jess NOTES FROM HERE When I became a public high school English teacher in Oak Park in 1994, I was terrified of teaching poetry. Poetry felt like a riddle I could never solve. How could I teach something that I myself didn’t understand? I muddled my way through with the poems I had been taught in high school, the very ones that made me hate it because they made me feel stupid and I couldn’t see myself in them. In 1998, I brought in a former student, Jonathan Vaughn, to rescue my poetry unit. I watched my students’ faces wake up as he connected music lyrics to poetry, explained that “rap” stands for Rhythm And Poetry, told them about poetry slams, and encouraged them to write and share their own poems. Imagine that! I was embarrassed and inspired at the same time. “Can we have a poetry slam, Mr. Kahn?” the students rang out. And we did. A week later, the student with the lowest grade in the class came out on top with a rap about his writing pad that he took with him everywhere. “Brandon, where the hell have you been hiding that!” was a song lyric that we all sang out together. This is when poetry transformed from enemy to ally.

The next year, I redesigned my approach to poetry with a focus on contemporary poets like Patricia Smith and Saul Williams, who wrote about topics my students could relate to and engage with. (Patricia was the first poet I ever brought to my classroom.) I also started thinking more about what was then called the racial “achievement gap” and is now more aptly called the “opportunity gap.” It has been a horribly resilient problem that has existed at our school since I started teaching there. This gap includes roughly a one point difference in weighted grade point average between white and Black students. And I thought one way to combat this rift was to create what is now called the Oak Park and River Forest Spoken Word Club.

We wanted the club to create a place of belonging for all our members, and particularly our Black students, where their experiences and voices could be heard loudly, proudly, and clearly. Each week, we celebrate our “study table all-stars” (those earning good grades) with snaps and cheers, while holding accountable and encouraging those with low grades. Students have set up peer-to-peer tutoring, and captains take pride when everyone in their group is an all-star. We teach writing craft, too, so students can see and show off their talent. So their words can resonate on the page, as well as the stage.

The Spoken Word club was conceived in large part because of students like Dan “Sully” Sullivan. Sully had the lowest grade in my class when I first met him. But before I knew it, he went from planning to drop out of high school on his seventeenth birthday to starring in our newly created Spoken Word Club. That is the beauty of the club: It has created a space to give students, like Brandon and Sully, a place to call their own, a place to belong. It also gave them a reason to show up to school in the first place.

Sully’s parents told me on several occasions that poetry “saved his life.” Poetry saved me in a way, too. It saved my career and changed the trajectory of my life. Teaching can be a draining profession, and I nearly abandoned it. But watching a community and its future leaders develop right in front of your eyes is an amazing thing. Seeing students who didn’t believe in themselves win national poetry prizes or earn full tuition college scholarships is like watching a magic trick: I’m still guessing at the secret behind it.

At the Oak Park and River Forest Spoken Word Club, we’ve built a legacy where rookies eventually become captains and where graduates come back to work with us. Because poetry is the starting blocks, the finish line, and most importantly, the baton. In Spoken Word Club, the phrase “respect the mic” reigns supreme. Our student leaders shout it out like an order if anyone dares to talk when someone is reciting a poem. It’s a call of pride and history and tradition and hope. Respect the mic—you have the floor.

—Peter Kahn Peter is right. I was an apathetic student. It wasn’t that I was a bad kid. I just didn’t like to do things like, you know, homework. It wasn’t my parents. I came from a supportive home. I’m lucky in that way. Apathy was a privilege and one I chose to exercise freely. It wasn’t even that I didn’t like school. I was searching for a place where I felt like myself, was accepted for everything that I am and was witnessed. I found that in the Spoken Word Club.

My senior year, I wrote a collaborative poem with fellow club member Michael Pogue for a poetry showcase at the school. We titled it “Meditation” and, though it was far from a quiet mantra, it was rhythmic and guttural, a battle cry to find peace in ourselves amongst the chaos of high school. “I only see clearly by closing my eyes then tap into a continuum of clarity / Very rarely do people bury barriers carefully.” Young adults, especially young men, are conditioned to build a fortress around their emotions as a method of survival.

Mike and I, through poetry and the club, began to learn how to break through the gates of the fortress. We had notebooks in hand while we dangled our legs over the large stone wall at Scoville Park and laughed while we watched the blur of suburban traffic. We talked for hours and worked to record it all in ink. We wrote poems for our fathers and prayers for our future selves. We’d practice in front of storefront windows so that we could see the reflection of our gestures and plot our stage points. We’d spend hours in an empty classroom after school to get feedback from Mr. Kahn. My friendship with Mike helped me develop a vulnerability and willingness to deepen my connections to others. This is what the Spoken Word Club gifted me. It opened me up to more than just a new way of learning, but also a new way of being in and interacting with the world around me.

In terms of the club’s success, there is an X factor beyond the poetry and its built-in community. At the heart of the program, there is Peter Kahn. When I was a junior in high school, he found me sleeping through class and searched for a way to reach me. It’s why so many of us have found a home in spoken word. It wasn’t just poetry that saved my life, it was a teacher who took the time to recognize that poetry has power, and he’s now helped generations of young people harness it, break through their own fortresses, and find a home in themselves.

I often joke that I was in high school for seventeen years. I spent thirteen years after graduating as cosponsor of the Spoken Word Club alongside Peter. Since high school, I have read poems, performed, and taught creative writing classes and workshops all around the world. I’ve received master’s degrees in poetry and English, and made appearances on HBO and NPR. None of this would have been possible without the Spoken Word Club. Not only because of what it taught me about poetry, but because of what it taught me about leadership, mentorship, collaboration, and friendship. The first time I taught poetry in a classroom at OPRFHS, I sweated through my Ecko polo shirt. I was bewildered, but I have learned bewilderment is the point at which all poems start. We dislodge from the immediate circumstances of our lives and discover something new there.

I am proud to say that my life as a student—befriending my bewilderment, making sense of and articulating my inner-world, learning to let people past the fortress, and then helping them through theirs—hasn’t been a lonely experience. It is one that so many other students have lived and are living out after joining the Oak Park River Forest High School Spoken Word Club. Though each of the poems in this anthology are events unto themselves, they open up to a larger sphere of community, one that lets us all in through the front gate. This book is a breathing testament to what happens when we truly listen to each other and celebrate how it sounds when individual voices speak up in unison.

—Dan “Sully” Sullivan We are so proud of the seventy-six poets in this anthology, some of whom are still in high school, others who haven’t put pen to paper in years, and others who have made careers of writing. They represent just a small percentage of those from our club who have been transformed by poetry. We welcome you to our home, where we’ve been poetically sharing our stories since 1999.

Copyright © 2022 by Hanif Abdurraqib, Franny Choi, Peter Kahn, and Dan Sullivan. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.