Chorus: Wild Fire

If you listen closely, you can hear their TV screens pour from the windowpanes, under the apartment doors, and out onto the streets. Everybody is listening to the news, and no one is listening to their hearts.

I am Hyacinth.

Mi a har best fren, Electra.

And we’re just two city girls . . .

Suh yuh sey, Ms. Trini-to-the-bone!

Okay, okay. We’re two city girls with island roots. We met in the foster care system, after one too many fights took us from our families’ homes and placed us as roomies in a group home slash detention center, wearing blue crew neck sweatshirts and matching sweatpants with one-size-too-small slippers. We sat in that weird-smelling facility until we were moved to neighboring foster care homes. Some might say we have a chip on our shoulders because we talk the truth loud. But really, we are over being talked down to, talked over, and completely ignored.

Fi Chuu.

You can say that being height-challenged brought Electra and me closer. Because for some reason, people think they can pick on people like us.

Dem pick pon mi, mi wi fight dem.

But you aren’t here to hear about our origin story--you are here to learn the stories of how we all got to this weird pandemic place in the first place. And you are in luck, because we keep our eyes wide open!

Serious. Wi see all a it.

No lies, we’ve seen it all. Okay, maybe not all--but a lot. Follow us. We have seen a granny spoon-feed VapoRub to a likkle one. We have seen fishermen pull seaweed from the mighty waters, clean all the sand free from the leaves, and make a cure with it. We have even seen a mother strap a baby on her back with thick kente fabric and machete a clearing through the sugarcane field for her family’s safe passage to New York City.

She and Electra’s mother moved from Kingston, Jamaica. And after my father passed away, my mother, big brother, big sister, and I moved from Trinidad and Tobago to Stamford, Connecticut.

We fine each odda unda strange circumstances.

Yes, Electra, we did find each other.

After we were both Scarlet Lettered as disruptive students (simply because we asked questions and demanded answers), we became used to being ignored. Adults often ignore the young people they don’t understand. And this is when you really see the trees from the forest. This is why Electra and I are chorus. We have seen it all.

Like duppy. People figet sey wi deh yah

We have seen People living behind surgical masks waiting for the world to end

People hoarding food and hand sanitizer

People afraid to be kind to other people.

I mean, we weren’t alive to witness the world surrender to the “Spanish” flu of 1918, the flu in 1957, or the flu in 1968. We only know what this rebuilt world looks like. And we know how to be good neighbors. We know to always be kind and say thank you. We know one should wait until everyone at the table has their meal in front of them before taking a bite. And we know we need each other to make the future possible.

Tank goodness we did raise fi know betta.

Malachi: Quinies, Part 1

It’s like one day, the planet woke up and evicted us all.

One day we woke up and didn’t have to go to school. It was just over. My entire freshman year in high school, poof ! Gone. My brother, an extremely annoying eighth grader: Maseo Jr. formerly known as Lil Maseo but now known as MJ, didn’t have school either. It was like we went to sleep angry about a test or whoever didn’t text us back, or whoever was cowardly enough to write someone else’s name on the bathroom wall in the locker room, and woke up to nothing.

Sure, the adults tried to pretend they knew what to do. Started online class check-ins a week later. But most of the students figured out quickly, if you turn your camera on to a pre-saved picture, then you might actually get some real work done on your current game of Fortnite. And sure, the adults tried to pretend they weren’t stressed out, weekly deliveries of wine bottles and face masks tossed everywhere our shoes weren’t. It lasted for a couple of months, until the Wi-Fi cut out. And we tried to stay on top of it all, but essential workers were quitting left and right. So finally, the phone towers were taken over by the ivy and various green waves of nature. It’s like the earth opened her eyes one day and was tired of all our plastic straws and Amazon deforestation and cracked dirt from black oil and minerals mining.

First, we were told it was a new strain of flu. One that made your chest fill up with water and mucus. One cough and the fire would plant a little firecracker seed in the base of your neck. In two days, the seed sprouted and began to crawl up your spine into the back of your skull and stretch all its legs across your brain. The adults thought this new strain would only affect old people and poor people. Only some of them were upset. But the ones who stood outside of senior citizen homes with handmade signs and teary faces weren’t upset; they were devastated. The news would plaster this picture on the screen and run every couple of hours. It was like a warning for us to stay home. The warning only seemed to work on people who cared about the elderly. Turns out, the president--my mama called him “that mean man”--was on the television screen with a red tie and orange face, instructing people to do homemade science experiments on themselves.

I asked Mama, “Why is he so mean? What’s the difference between him and the rest of the people in charge?” She stopped cooking slices of turkey bacon on the stove and looked in the corner like the answer might live between the pop and the sizzle of our breakfast.

“He abuses his power. He told people to inject bleach to kill the virus! Like it was a joke.” She scoffs. “What did I tell you about cleaning supplies?” She goes back to tending to the sizzle on top of the open fire.

“No drinking cleaning supplies,” I chant like a song I don’t like but know by heart because it plays on the radio every hour of every day.

“Malachi, I taught you that in kindergarten,” she exclaims, shaking her head. “It’s like some folks forgot the basics and just listen to anything these days. But they can’t see--anyone who makes hate speech is doing it for profit, and money doesn’t care about the sick--as long as the bottom line isn’t affected. You just watch. This kind of talk ain’t no different than what your great-great-grandfather went through when they tried to take his land and his dog back in Louisiana. He prevailed, and we kept that land in the family despite them trying to ruin the soil and spoil the crops. People like that only listen to one thing: money. This is just the beginning!”

She balances her weight on her bad foot. You can tell it’s bad because it’s the only foot that swells like a bag of potato chips that’s been in the bodega window too long. She shifts her weight and keeps talking. “In other places around the world, this sickness is happening, and no one is being forced to work. They are allowed to take care of their families and their health. But not this so-called leader. Oh no, he wants us back at work as if money is more important than people.”

I nod like I understand, but I don’t understand any of this, not really. As far as I could tell, Brooklyn has always been this way. Some rich people live there, and right across from them are ready-made millionaires in public housing. We all go to the same bodega. We all order from the same Chinese food spot. I just thought some of us got a doorman and some of us got a cigarette lady welcoming us home. But Mama is kind of telepathic because she answers the thoughts in my head.

“You may not notice the difference now. But as you grow older, you will see the difference, soon enough. Just keep your eyes open. See everything.”

And just then the man with the worst advice ever says take a daily dose of a drug that people with lupus need. And I had to look it up for a research paper back when we were still in virtual school. A six-syllable word that made everybody catch their breath: hydroxychloroquine. It costs so much people started selling their food stamps for half the price, just to afford a month’s supply. The manufacturers and bootleggers were selling it under the counter, online and rationing it out like it was water in a desert. Then the bootleggers began to see unprecedented profits and decided to split the drug with other substances to make it stretch, so they could make even more money.

This is when people started disappearing. We would be in our online classes and parents would have to do a “check-in” at the end of the week. Some of the parents’ screens were just fuzzy static. Once where a concerned or tired face peered into the screen, now nothing. At first, me and my friends joked during Fortnite “zombies.” And then one of the Fortnite players stopped laughing with us. It got eerily quiet.

The avatar stopped moving on the screen and everything, and a voice called out, “They’re not zombies. And she might be a Quinie--but she’s my mother no matter what.”

Playing the game after that got really tense.

“Sorry. Maybe someone in the neighborhood has seen her?” I asked.

But deep down, I knew, people had already stopped talking to each other on the street weeks ago. Wearing masks around your face to keep the sick away was one thing, but when you were walking around afraid someone would rob you or hurt you (even if you weren’t wearing a mask), they became even more distant and rude. No more holding doors open for one another. No more good-morning greetings when passing each other on the street. I was still thinking about how masks and sunglasses could make you feel more invisible than you might already feel, especially if you live in my part of Brooklyn. Especially if you look the way I do.

The voice cracked through the headphones. “I can’t find her. I looked everywhere, even in the dark alleys near DUMBO. You know where the bridge arch is blocked? I can’t find her anywhere. It’s just not funny, that’s all. I gotta go.”

And that was that. We all stopped talking that day. I stopped playing altogether a few weeks later. Something about playing a game of strategy and death in silence makes it feel too real. Ever since then, I’ve been haunted by the voice that cracked on the other side of the headset. I mean, I consider myself lucky. I never had to think about what happened to Quinies. When I started to look more closely, or as Mama instructed, “see everything,” the stories appeared everywhere.

Personal accounts of how these parents, aunts, uncles, cousins, sisters, brothers all just disappeared. And the people living with lupus ran out of ways to get their medication. Before, the drug was inexpensive and easily accessible. But now, the illegal drug is as hard to come by as a bar of gold. Everybody was living in the shadows of their misplaced dreams. But the people with lupus didn’t disappear. They just became unalive.

My mother’s best friend, Akeena Sil Lai, had lupus. But we are never allowed to call her anything but Auntie Akeena. She used to watch us kids when Mama had to work at the beer factory in Newark. Which was the worst because Mama had a two-hour train and bus commute, which means she was always tired. But yeah, we couldn’t even go to Auntie Akeena’s funeral. It was too dangerous to go outside. You never know what you’re gonna walk into. So, Mama let us light a candle and put it in the window.

That night, it was so still. I didn’t even hear the rats scouring the streets. No loud motorcycles tearing up and down the street playing DMX’s Greatest Hits. It seemed no laughter or music that didn’t already live in your own body existed. It’s been like this for months now.

One day, maybe the third day after Auntie Akeena had passed away, Mama lit the candle and went to prepare breakfast before a big whoosh from the other side of the window blew the candle out. It was the first movement we felt in a long time. It was like a big mouth pushed out a big gust of air made it all go dark.

Malachi: Quinies, Part 2

The adults had it wrong.

They thought it was a pandemic that we would all survive.

“Once it gets hotter, it’ll be just fine!” they said.

People started having picnics as the virus mutated and evolved. We thought we could evolve with it. Businesses opened outdoor seating where black garbage cans once congregated, and repurposed sparkling water bottles holding a fistful of dying flowers positioned in the center of their tables became a brunch scene. People lined St. Marks Place in the city where the road was so uneven, we would pretend the potholes were booby traps and we attempted to hop each unnatural divot with one foot on the pedal and one in the sky--prepared to make our spill the funniest thing we talked about on the ride back across the red fated bridge to Brooklyn.

The mayor said, “Get ready for summer!”

The racist president said, “Summer will kill the virus.”

The governor said, “Be kind to each other and mask up.”

The medical doctor who was older and frail-looking laughed at them all. He said, “It’s a virus. It cannot be reasoned with.”

The adults had it all wrong. They thought they could laugh, swipe right, and play away.

That we would all get it and some of us would be fine, and most of us would get sick, and hopefully, for those that could afford the medicine, the sick would heal.

The virus said, “50,000 dead. 135,000 sick.”

The virus said, “110,000 dead. 1 million sick.”

The virus said, “205,000 dead. 58 million sick.”

The virus said, “500,000 dead in the United States. 102 million sick.”

The medical doctor, who was old and frail, looked sad. He looked like someone who didn’t want to play the “I told you so” game.

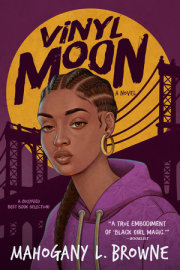

Copyright © 2025 by Mahogany L. Browne. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.