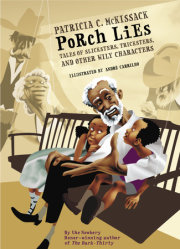

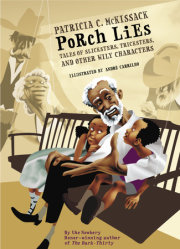

Mis Martha June was a person I thought incapable of telling a porch lie. I was wrong. Always prim and proper, she was a churchgoing woman who spoke in quiet, refined tones with her mouth pursed in the shape of a little O. She was never without a dainty pocket handkerchief tucked in her sleeve, which she gingerly used to dab perspiration from her brow. A woman of Mis Martha June’s qualities did not sweat.

She owned a bakery that was known for having the best coconut cream pies in the world—same recipe her mother used, and her mother before her. And no customer was more faithful than a wily character named Pete Bruce, about whom she loved to tell stories. He was considered the prince of confidencers, and the idea of Mis Martha June having anything to do with the likes of him was about as odd as a fox and a hen striking up a friendship.

“Pete Bruce was the worst somebody who ever stood in shoes,” Mis Martha June always began in her quiet manner. But then she’d add quickly, “I’ll be the first to admit, however, he could make me laugh in spite of myself, especially when he threw one of his million-dollar smiles my way. . . .”

Here is the rest of the story as she told it long ago on our front porch, on a late summer night.

----

I was near ’bout ten years old when I first laid eyes on Pete Bruce. He was a full-fledged rascal and I knew it! If you went by looks alone, Pete Bruce was pleasing enough. Had a nice grade of hair, wore it slicked back with Murray’s hair dressing oil and water; had plum black skin, even darker eyes, and a devil-may-care swagger. As I recollect, he always loved big Stetson hats, flashy cars, and loud suits. Stood out. Pete Bruce liked that—standing out, being noticed and all.

Mama sold coconut cream pies to passengers at the bus station back then, and her reputation as a super baker was known far and wide. Most people called her the Pie Lady. I helped Mama on weekends or when I wasn’t in school, so folk started calling me Li’l’ Pie. And a few people still call me Pie to this day.

It was an ordinary Tuesday morning when Pete Bruce stepped off the bus. Hot! My goodness, it was hot as blue blazes. Yet I noticed that this man had on a suit, fresh and crisp as if he’d just taken it off a cleaning rack. “How come he looks so neat when everybody else looks like they slept a week in their clothes?” I wondered out loud.

“A sign of good material,” said Mama, who was studying the stranger as a potential customer.

We watched as he dabbed his brow with a perfectly folded white linen handkerchief. He checked the crease in his hat and placed it squarely on his head. Then he studied the surroundings, as if testing the wind, getting the lay of the land. Spying Mama and me, he picked up his carpetbag and started on over.

The man had an ageless body. By the bounce in his step, he could have been twenty, but the set of his brow told the story of a much older man. “Morning,” he spoke real polite-like, flashing the biggest grin. “Name’s Pete Bruce. Them coconut cream pies?” he asked Mama, examining the display she had arranged on the hood of our ’28 Ford.

“Welcome to Masonville,” Mama said cheerfully. “This is my daughter, Martha June. And yes, sir, these are coconut cream pies made by none other than Frenchie Mae Bosley, yours truly.” Mama extended her hand and Pete Bruce took it and pumped it like a bellows. He grabbed mine and shook it, too, and I noticed how soft his was. This was not a man used to hard work.

“Pies do look good,” he said, still holding that grin like an egg-stealing fox.

“Here, have a piece.” Mama always let people taste a sliver of her sample pie. It was great for business, ’cause not one person had ever taken a taste and not bought a whole one. Sometimes they bought two.

Pete removed his hat—the way a man does when entering a church or a funeral—and clutched it to his chest. “No, ma’am,” he said ever so courteously.

“What’s the matter?” Mama said, sounding sympathetic. “You got sugar?”

He shook his head, lowered his eyes, and leaned on one foot and then the other. “No, ma’am, I aine diabetic.” He sighed heavily.

“Well, what, then?” Mama was curious now.

“I mean no disrespect, Miz Frenchie, but there’s a lady over in Steelville, Miz Opal Mary, she bakes the best cream pies in the world. Ummmm!” He closed his eyes as if eating one right then. “I—I have no doubt that your pie is delicious, but it just can’t be as good as Miz Opal Mary’s.”

Mama’s back stiffened. “How can you say that without having eaten mine?” she replied curtly.

Pete Bruce went back to shifting his weight from one foot to the other, eyes cast downward. “I’m sure your pies are fine, ma’am. But I’d rather not disappoint the last memory I have of Miz Opal Mary’s rich, creamy, oh-so-sweet coconut cream pie.”

Mama was beside herself. “I assure you, young man, there is no way in the world you would be disappointed if you ate a slice of my pie.”

“I can’t be sure,” Pete said, looking like it made him sad to say it.

Quickly Mama cut a small wedge from her sample pie. She shoved it at Pete Bruce. Slowly, as if it pained him to do so, he put the whole thing in his mouth and chewed on it with his eyes closed. “Ummm,” he moaned.

“Well, sir,” said Mama confidently, “tell me the truth. Wasn’t that the best thing you ever put in your mouth?”

Pete Bruce opened his eyes and shook his head. “I wish I could say, but . . .”

“But what?”

Pete shrugged. “I’m confused. It’s hard to tell whose is better. Yours? Or Miz Opal Mary’s?”

Copyright © 2006 by Patricia McKissack. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.