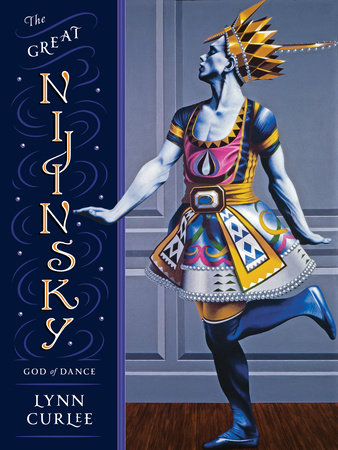

Prologue Wonder of Wonders My senses were all blurred that night. The familiar barriers between the stage and the audience were broken. . . . The stage was so crowded with spectators that there was hardly room to move. . . . Hundreds of eyes followed us about. . . . “He is a prodigy” and awed whispers “It is she!” . . . Somebody exquisitely dressed staunched the blood trickling down my arm with a cobwebby handkerchief — I had cut myself against Nijinsky’s jeweled tunic. . . . Somebody was asking Nijinsky if it was difficult to stay in the air as he did while jumping; he did not understand at first, and then very obligingly: “No! No! Not difficult. You have to just go up and then pause a little up there.” — Tamara Karsavina

PARIS May 18, 1909 On a balmy evening in late spring, the Théâtre du Châtelet was booked to capacity, with nearly three thousand people in the audience. A troupe of dancers from the legendary Russian Imperial Ballet, the czar’s own dance company, was about to appear for the first time in the cultural capital of the Western world, and this preview performance was the hottest ticket in town.

As the theater slowly filled, the sophisticated crowd was keen with anticipation, chatting excitedly among themselves. The famous and the talented, the wealthy and the powerful, the fashionable and the beautiful—all in formal evening dress—filled the orchestra seats and the dress circle above. The crème de la crème of Parisian high society held court from their private boxes. Middle-class patrons of the arts decked in their Sunday best occupied the lower balconies, while artistic young bohemians wearing shabby dark clothing and scarves around their necks found a place in the cheap upper tiers.

The atmosphere was festive. Fresh paint had brightened up the old theater, along with new scarlet velvet hangings and crimson carpeting. The management had the inspired idea to seat only beautiful young women in the first row of the dress circle’s sweeping curve, giving out tickets to selected actresses and dancers. As the audience assembled, the dazzling sight of all sixty-three young ladies seated in the “diamond horseshoe” created a sensation. Blondes alternated with brunettes and redheads, all with hourglass figures and low-cut gowns in the style of the belle époque. Pale bare shoulders were set off by glittering diamonds and lustrous pearls, and elaborate hairstyles featured egret and ostrich plumes.

The year before, a Russian opera company had traveled to Paris and created a sensation with a lavish production of an opera never before seen in the West—

Boris Godunov, by Modest Mussorgsky. This tragic story of a medieval Russian czar electrified jaded Parisians with its exotic subject, gorgeous music, splendid singing, and magnificent stagecraft. Russian opera had returned for a second season, and now Russian ballet was about to be added to the mix.

At exactly half past eight, after the traditional three raps from backstage, the lights slowly dimmed, and the restless audience settled down. The conductor tapped his baton on the music stand to cue the orchestra, and with a soft roll of the kettledrum, the music began.

The curtain rose on

The Pavilion of Armida, a confection of a ballet about a Gobelins tapestry that comes to life. Costumes and decor were in the style of the eighteenth-century French court, and for the second scene, two real fountains with water piped in from the Seine flanked the stage. The audience was swept away by the spectacle.

Eventually a young man took the stage with two ballerinas for a pas de trois. The precision and beauty of the routine riveted the audience. They had never before seen dancing like this. In French ballet, male dancers, when they appeared at all, merely supported the ballerinas, but this dance was centered upon the youth, who moved with such passion and athletic power that a murmur swept the crowd. At the end, instead of gracefully walking off with his partners, the young man impetuously leaped offstage. The audience gasped as they saw him go up into the wings, where they could not see him come down—it was as though he’d taken flight. After a stunned pause, a tremendous wave of applause rolled across the footlights.

Then the dancer returned for his solo—a thrilling series of pirouettes and high jumps, during which he seemed to float suspended in midair. The audience cheered. After solos by the two ballerinas, all three dancers returned for a reprise before taking their bows to a thunderous ovation. When the lights came up at the intermission, the audience scanned their programs to find out about the young man. His name was Vaslav Nijinsky.

The next performance that night was the hour-long second act from the opera

Prince Igor, by Alexander Borodin. The curtain rose to reveal an encampment on the Russian steppes—an immense, desolate landscape of rolling hills beneath a golden sky with pink clouds and plumes of smoke rising from the tents of the Polovtsi, a Tatar tribe. After a lot of impassioned singing, the climax of the act featured the corps de ballet in an epic spectacle of choreography known as the “Polovtsian Dances.” Colorfully garbed groups of warriors, slaves, men and women, boys and girls joined in a frenzied climax accompanied by chorus and full orchestra with pounding drums and clashing cymbals. The audience went wild.

Everyone was aware that something extraordinary was happening. In France the ballet had come to be “regarded as a frivolous art form unsuited to serious artistic expression.” The Russians were a revelation. During the second intermission, some bolder members of the audience invaded backstage to watch from the wings, wanting to see the dancers up close.

The final act of the evening was

A Banquet. The curtain rose on a magnificent medieval Russian banquet hall as the setting for a series of dances choreographed to music by different Russian composers. Nijinsky appeared in a segment of A Banquet called “The Lezginka,” his face painted dramatically and sporting a rakish mustache. He danced the lezginka, a folk dance performed by a group of men in high boots. For the segment titled “The Golden Bird,” Nijinsky returned with one of his partners from

The Pavilion of Armida, Tamara Karsavina. They performed a lovely, intricate pas de deux, he dressed and bejeweled as a Turkish prince, and she as a bird with flaming ostrich feathers. Once again, the audience was dazzled by their virtuosity, and most particularly by Nijinsky’s power, grace, and charisma. One spectator said about their impact, “When those two came on, Good Lord! I have never seen such a public. You would have thought their seats were on fire.” To conclude the long evening, the entire company paraded to a march by Tchaikovsky, the best known of the Russian composers. This grand finale brought down the house amid a hail of cheers and bravos. The audience demanded seemingly endless curtain calls.

The legend of Vaslav Nijinsky as the greatest of all dancers began with that first spontaneous leap offstage in The Pavilion of Armida. It has been said of that glamorous night that “Nijinsky took off his costume, removed his make-up; and went out to supper and fame.” When notices of the evening were published in the newspapers, the critics hailed the Russian ballet as spectacular entertainment—a triumph of Russian art—and compared the event to a royal fete at the court of King Louis XIV. The music, the costumes, the decor, and all the featured dancers were singled out for praise. Tamara Karsavina was astonished to discover that she was now “La Karsavina.” And Vaslav Nijinsky was immediately hailed as a phenomenon—a “wonder of wonders,” and even “God of the dance.” He was twenty years old.

Copyright © 2019 by Lynn Curlee (Author/Illustrator). All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.