Uly I’m in love because a clown got handcuffed to a nun.

Last November I was in this dumb-ass school play called

Hostages and Hot Plates where this rich Connecticut girl holds a whole restaurant hostage until her parents agree to let her marry this penniless-as-hell guy she’s mad thirsty for. The parents are okay with the dude being poor, but they’re not okay with him being from Neptune (yep, the planet). So the girl holds everybody at the restaurant—her parents, her little brother, her aunt (who’s a nun), a snooty middle-aged businesswoman, a squabbling elderly couple, a clown, a magician, and me (I play the damn waiter)—at gunpoint until her parents are okay with Neptune. Of course, hijinks ensue. At one stupid point, the clown and the magician—who are there for the little brother’s birthday party—get into a fistfight because the clown thinks he knows more tricks than the magician who thinks he’s funnier than the clown and during their scuffle the magician bumps into the snooty businesswoman who accidentally pours cranberry juice all over my white uniform. For some reason, that makes me faint. I especially hated that part, by the way. I’ve never fainted before in my life. For those of you who don’t know: black folks don’t faint. I’m not sure why; we just don’t. Evidently the playwright missed that memo and forced a brother to faint every night in front of administrators, teachers, and fellow schoolmates. Anyway, after a while the hostage negotiator persuades the girl to let all the hostages go, but her aunt—the nun—decides to stay with the girl, and the clown—feeling guilty about some real disturbing shit he’s done over the years (it’s a long-ass list that I don’t have time to get into right now)—refuses to leave the nun alone with the girl so he handcuffs himself to the nun. The hostage negotiator eventually breaks into the restaurant and, seeing me unconscious on the floor in my cranberry-juiced white suit, thinks the girl blew me up and is about to lock her up for life, but then I wake up and the police chief ends up locking her up for eleven months (the girl’s parents are really tight with city council).

And the girl’s parents end up still not being okay with Neptune. So the girl went through all that drama for nothing.

But I went through all that drama for something. If it hadn’t been for that heap of horse-vomit that had the nerve to call itself a play, I wouldn’t be in love right now. So as much as I hated that play, I can’t think and talk about it enough, even though it ended three months ago. My grandfather (R.I.P.) used to say, “Even the most beautiful gardens start with shit.” At the time, I didn’t know what he meant. Now I do.

It started at the end of a quick last-minute dress rehearsal just a couple of hours before our grand opening-night performance. Friday night. The clown and the nun were handcuffed to each other, as usual; but this time, nobody could find the key to uncuff them. Stuart Baldwin, our props guy, was an incompetent asshole even on his most bacon day and he’d misplaced it. It didn’t take long for Panic to be the thirteenth member of our twelve-member cast. Everybody started scurrying around our handcuffed nun & clown, whipping back and forth across the damn stage, frantically checking under tables and chairs and heavy curtain folds. It wouldn’t have been so bad if our opening night wasn’t less than two hours away, but it was. Even Ms. Rothstein, who’s normally so calm she could probably have a picnic lunch on a flying missile, was starting to look pale and anxious. Looking even worse were Lori McCormick—the clown—and Harriet Jennings—the nun. There had been rumors swirling around that they wanted to split each other’s head open—something to do with Harriet Instagramming a selfie she’d taken with Lori’s boyfriend a couple of weekends earlier and Lori body-shaming Harriet by Tweet a couple of days later; I don’t know if any of it was true but the quiet, intense way those two girls stared at each other while the rest of us scampered around told me that we needed to find that key sooner than later, feel me? I swear I’d never seen a clown and a nun look so angry.

So, just to lighten the mood, I shrugged, pointed at their handcuffs, and said, “Looks like y’all are gonna need a train to come by soon.”

The Magician (I forget the name of the kid who played him) gave me a confused look and asked, “Train? What do you mean?”

I said, “You don’t know that movie?”

“What movie?” he said.

I looked at some of the other cast members and asked them, “Y’all don’t know that movie?”

They blankly shook their heads “no.” Even Ms. Rothstein was looking at me like I was some mile-long quadratic equation handwritten in Sanskrit on paper made of Juicy Fruit gum.

Before I could feel like even more of an alien, Jerry Hoyt the stage manager yelled, “Found it!” The key. It was under one of the seats in the front row of the audience area. We all put our heart attacks back on the shelf and Ms. Rothstein finished giving us the final notes.

During the performance, toward the end of the play, the snooty businesswoman, as usual, handed me a folded dollar and said, “Here you go, young man—this should help with the cleaning bills.”

And, as usual, I frowned at the folded dollar and said, “Thanks; this’ll go a long way toward cleaning the left lapel.”

Sallie Walls, the girl who played the snooty businesswoman, always gave me an actual dollar (which, of course, I always returned to her after the play). But on this particular night, she gave me the dollar with a purple Post-it note attached. I didn’t notice the Post-it until minutes after the play when we were all backstage. I took the folded dollar out of my pocket, saw the purple edge peeking above the bill’s right side, unfolded the dollar, and saw this message on the Post-it:

The Good, the Bad and the Ugly? I found myself smiling at the note. Then I looked up and tried to find her in the crowd, my eyesight slicing past patches of still-costumed cast members, moving past the magician, moving past the damn clown, moving past the nun, moving past the hostage negotiator, and finally landing on the fifteen-year-old blond girl, make-upped to look forty-five, still in her businesswoman suit. She was leaning against the big dressing room’s wall, alone, staring at the floor with one hand idly cradling her neck, looking the way an apple might look in a room full of bananas. The apple knows it’s surrounded by fellow fruit, but what do you talk about? You’re round and red, they’re long and yellow; you have skin that everybody eats, they have skin that nobody eats; you have seeds, they don’t. I knew that look because that was the way I felt the whole time I did that play; shit, that’s the way I feel the whole time I’m at this school.

I made my way through the wilderness of the weirdly dressed, holding the purple Post-it note higher and higher as I got closer to her.

Pointing at the Post-it, I nodded at her and said, “Tuco is handcuffed to the guard—”

“—and he tells the guard he has to go to the bathroom,” she said, smiling.

“But they can’t go to the bathroom ’cause they’re on the train,” I said.

“So the guard gets up and opens the train door so Tuco can let it fly from the train’s doorway,” she said.

“But instead of lettin’ it fly, Tuco grabs the guard and pulls him off the damn train,” I said.

“And they both roll down this gravelly hill—” she said.

“—And Tuco slams the guard’s head against this big rock over and over, killin’ him—” I said.

“—But then he remembers that he’s still handcuffed to the guard . . .” she said.

“And who wants to spend the rest of his life, draggin’ around a dead prison guard?” I said.

“Not me,” she said.

“So then he tries to break the handcuff’s chain—” I said.

“—with the handle of his gun,” she said.

“But that doesn’t work—” I said.

“—so then he tries stretching the chain as hard as he can, but it still won’t break,” she said.

“Then he looks up and sees the train tracks, and he gets this idea . . .” I said.

“He lays the guard in the middle of the track and lies down on the other side of the track and waits for the next train to come . . .” she said.

“And then the train comes speedin’ by . . .” I said.

“And the train’s wheels slice through the chain . . .” she said.

“And now he’s free . . .” I said.

“And he runs after the train and hitches a ride on the back of it,” she said.

We both laughed. It kind of felt like we should’ve given each other a fist bump or a high-five or something, but a fist bump felt too brotherly and a high-five felt too corduroy. So we kept our hands at our sides. I said, “That was bacon as hell.”

She nodded. “Totally.”

There was a pause while we stared at each other.

Then I said, “Oh, and here’s your Georgie.” I handed her dollar back.

“Oh, thanks,” she said, pocketing the bill, still staring at me.

“I’m mad impressed you know about that movie,” I said, then motioned back at the nun, magician, clown, etc. “You’re, like, the only one who got it.”

She said, “It’s my favorite movie.”

My eyebrows went up. “Real talk?”

She nodded.

“Damn,” I said. “It’s mine too.”

Now it was her eyebrows’ turn to go up. “Really?”

I said, “How badass was Eli Wallach in that movie?”

She said, “Oh my God, he so made that movie!”

I nodded. “Real talk. I mean, I know Eastwood was the star and everything, but Wallach owned that shit! It’s hard as hell to be sociopathic and funny at the same time, but my man pulled it off!”

Sallie said, “Completely. I mean, he took this, like, completely despicable, immoral character and made him the most likeable guy in the movie! Blondie and Angel Eyes were supposed to be the better guys, but if I was throwing a party or something, Tuco would be the only one I’d invite. I mean, I’d have to hide everybody’s jackets and wallets before he came of course, but I’d still want him to come.”

I laughed. I couldn’t believe I’d never noticed that her smile was brighter than the room’s dozen lights.

She said, “Oh, and you know another cool thing about that movie? Okay, we know Blondie is the Good, Angel Eyes is the Bad, and Tuco is the Ugly. But I think the movie was trying to say that each of them was really all three things. I mean, Blondie did some things that were bad and ugly, and Angel Eyes did some things that were good and ugly, and Tuco definitely did some things that were good and some things that were bad.”

After giving what she said some mind time, I said, “Wow, I never thought of it that way. You’re right.”

Behind me our fellow cast members were getting louder and louder, playing some game with a foam Frisbee.

Sallie threw a distracted glance at them then moved her eyes back to me and said, “Hey, you wanna get outta here for a while—like, go out to the staircase or something? I can’t hear myself think in here.”

I nodded. “Bacon.”

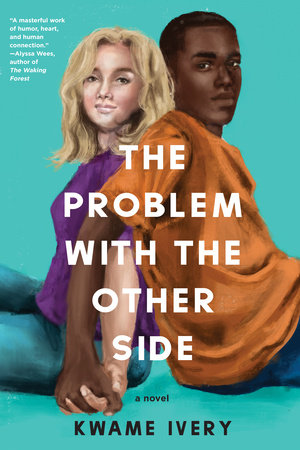

Copyright © 2021 by Kwame Ivery. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.