Introduction

In my life, there is Saigon, my childhood city, and there is Harlan, my daughter. One is loss and the other is love, although sometimes loss and love are intertwined. Both are volcanic, invasive experiences, their own particular battle zones, full of love and warmth. All-powerful, all-encompassing, searing, awakening. Once experienced, they take over your life, altering the very cells in your body, both in the moment and in retrospect.

I am writing as a refugee who lost a country and as a mother whose love is vaster than even the vast parameters of loss. In Vietnamese, the word for country is a combination of earth and water, elemental and archetypal. Traditionally, the Vietnamese are tethered to their ancestral home, born of land and sea, the way newborns are tied umbilically to their mothers, sharing one swollen, tightly packed body, ferociously, bound almost despotically by flesh and blood.

For all of us refugees who enter America with our contingent lives, there is the all-powerful, all-venerable American Dream. Do we follow it? Are we trespassing when we enter it? Or do we float into the dreams we invent ourselves? Having witnessed so many refugee families struggling to make it, I wonder whether the American Dream is really for dreamers. Are you dreaming if you're working twelve hours or more a day?

It might seem strange that being a refugee and being a mother feel so similar to me, but both involve a tortuous and lifelong drive in search of home and security-in one case for oneself; in the other, even more furiously, for one's child. The journey of a refugee, away from war and loss toward peace and a new life, and the journey of a mother raising a child to be secure and happy are both steep paths filled with detours and stumbling blocks. For me, both hold mystery. It is like crossing a river on a monkey bridge. The bridge, indigenous to the Mekong Delta, is handmade, with slender bamboo logs and handrails. It is frail and slippery, and crossing it requires agility and courage; it is both physical and mental. I have not made my crossing alone but have had fellow travelers on this bridge-we could call them darker selves that emerge from the hidden, almost mystical shadows.

Carl Jung saw shadow selves as selves that are cradled in the darkness and lie outside the light of consciousness. But what I think of as my shadow selves are denser, perhaps more fragmented from the self than Jung's original use of the term. They might seem like strangers at first, unknown, unknowable, and as a result frightening, a presence manifesting unruly states that had to be fought with or unshackled from. Over time, with a deeper reservoir of understanding, I have come to see them as guardian angels, as they are now more integrated with me than not.

After more than forty years in the United States, I still feel tentative here at times. And after seventeen years of being a parent, I continue to venture through motherhood as if it's a new culture. No matter how many parenting books I have read or how much advice I have received, I still feel like an immigrant in the universe of motherhood. As I tentatively make my way through this landscape, I find that I vacillate more than I am certain, shifting my terms of engagement more than digging in. Like an immigrant newcomer, I am ambivalent. I question myself, especially when my precocious kid sarcastically unleashes comments like "Great parenting, Mom" after I make a decision she doesn't like. She sounds so sure in her skepticism, and her certainty stands in stark contrast to my inner uncertainty.

Even something as basic as language-mother tongue, which for me is Vietnamese-posed a dilemma. I wasn't sure whether I should speak it to Harlan when she was a newborn. Even something as beloved as a country or a language could be a burden. And I wondered whether it was better for her not to be hyphenated or fragmented in any way. My husband, Bill, didn't speak Vietnamese. There would be no conversation. She would hear only my monologue. So I didn't stick to a Vietnamese-only regimen with her. I wanted to give her what I did not have and have not been able to achieve: wholeness. I wasn't sure I wanted her to be disjointed and bifurcated like me. By the time I changed my mind and saw hyphenation as an unconventional form of wholeness, as having a set of twos instead of multiple divided halves, her little brain had become an English-language brain. Now she would have to learn Vietnamese and any other language as a second language. That delayed decision remains a moment of regret.

Harlan was born in the United States, far from Vietnam, but I have bequeathed Vietnam to her whether I wanted to or not, sometimes as a gift, sometimes as a burden, but always as a marker or an imprint. I lost Vietnam when I was thirteen years old, in 1975. Forty years after the fall of Saigon, in 2015, my daughter herself turned thirteen, which for me meant the past had turned to the present, bringing itself to me in a singularly haunting act once again.

This was deeply poignant to me, perhaps because I saw it as life coming full circle, like a serpent swallowing its tail. Or maybe it is because humans need to find order and symmetry in life, and the tick, tick of calendar and clock in increments of five and ten creates the illusion that we can organize and mark time in comprehensible segments. For this momentous fortieth anniversary of the fall of Saigon, we went to see Rory Kennedy's film Last Days in Vietnam in Westminster, California, home to one of the largest Vietnamese diaspora outside Vietnam.

The theater was packed with Vietnamese who, like me, nurtured a deep elegiac longing from afar for the country we had left. Having watched Vietnam the country and Vietnam the war dissected in slanderous misproportion by Americans all these years, all of us, made to feel uncertain of our knowledge and our memories, returned yet again for another American interpretation of Vietnam, full of hope that something would be told right this time.

Seeing the film was one way for me to share my family's history with Harlan. We'd talked so much, but she'd never seen Vietnam on TV or in a movie. We held hands and we cried. We saw one city after another fall as the United States stopped supplying guns, ammunition, and even replacement parts. Come what may, whatever the consequence, whatever the wreckage, the war had to end, as far as America was concerned. After the first few minutes of the movie, however, I closed my eyes, casting myself adrift in my compartmentalized head, insulating myself from the screen. I was at the movie theater, but not really. I could be there, but also not. I knew how to detach, float away, without letting on that it was happening. Forty years ago, I too had witnessed these apocalyptic events from a TV in the living room in Avon, Connecticut, where I had been sent to live with an American family before the country's collapse.

I couldn't help but wonder whether I would be able to send my daughter off, away from country and family, to live with another family without any certainty that I would ever see her again. What would have to happen in our lives for me to take that action?

Harlan Margaret is my one and only child. In a dreamlike way that turned out to be real, I felt she was alive inside me almost as soon as she was conceived. Before the pregnancy was even advanced enough to be confirmed by a test kit, my body already changed, reconfiguring to make room for this new nudging, jostling, carnivorous being. Swollen breasts. Tender belly. Voracious hunger. Insatiable desire to nap. And from the moment the pregnancy was confirmed, I found myself measuring time not by reference to it in my own life but rather into the projected future of hers.

Both Bill and I were law professors. And so our daughter was named after one of the great justices of the United States Supreme Court, the august and magnificent Justice John Marshall Harlan from Kentucky. In 1869, he rejected separate but equal, the prevailing principle in the United States used to justify racial segregation, when he alone dissented from the majority in the infamous Plessy v. Ferguson case. I also wanted to give my daughter a gender-neutral name, and incidentally, the name Harlan also has Lan in it. In that way, we are intertwined with and embedded in each other.

The name Margaret came from Aunt Margaret, who had taken me in and cared for me when my parents sent me off in 1975. I was to be adopted by her and her husband, Fritz, our precious family friend, if South Vietnam fell and my parents couldn't make it out. Margaret was also the name of my daughter's grandmother on her father's side: Margaret Ware, a precocious, independent, intelligent woman who grew up in Santa Rosa, California, and entered Stanford University at age sixteen, graduating in three years. A California state park has a dedicated redwood grove and commemorative plaque carved with her full name, Margaret Ware Van Alstyne. The family had bought hundreds of acres of redwood forests to save them from commercial lumbering and donated them to the Navarro River Redwoods State Park. Until Bill died in 2019, trips to and stories about the redwood forests were part of Harlan's family heritage.

I also gave her a Vietnamese name, Nam Phng, which means "in a southern direction"; that is, toward "Nam," Vietnam. It was also the name of Vietnam's last empress, a figure considered a symbol of national unity and pride in Vietnamese history.

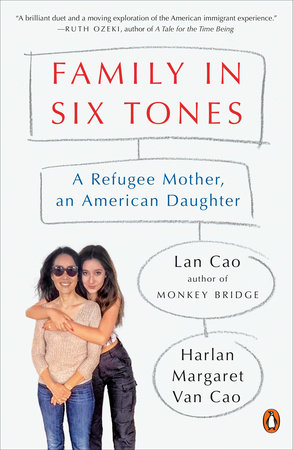

I thought if I had to carry a child for nine months, the child should take my last name, but in the interest of equality, I generously suggested using both our names. My husband's last name is Van Alstyne; mine is Cao. And so we made a new last name for Harlan: Van Cao, which seemed egalitarian enough. But in reality, although he probably didn't realize it, I won because Van merely means "from" in Dutch, and what we have in the end is Harlan Margaret "from Cao."

She might be, biologically speaking, from me, but from the moment I was pregnant, it felt as if we were sinewed together, as if I were also from her-motherhood and babyhood mixed together. The Vietnamese also believe that the mother and child relationship begins when the child is in the mother's womb. The relationship can be nurtured and developed as the child grows, and when the child is born, it is already one year old. It was natural for me to talk to her, to place the CD player close to my belly when I played music, to read out loud to her. We were very sensitive to each other's movements. I could feel her head against my belly, and sometimes I could almost grab her elbow and heel with my fingers to move her to a position more comfortable for me. My coughs were usually followed by intense, almost violent hiccups on her part-more than 150 once. Sometimes I could summon her by tapping on my belly rhythmically, and I could feel her respond to my call-our private code-by moving more vigorously.

Because I was almost forty when I became pregnant, it was recommended that I have an amniocentesis. What happened during the procedure turned out to be a fairly accurate predictor of Harlan's personality. Naturally, I was nervous because the procedure is invasive and carries a risk of inducing miscarriage. Amniocentesis could not be done earlier than sixteen weeks, and by that time, I had already fallen in love and bonded with the baby, having felt her movement and the shape of her body pressed against mine. This way in the morning, that way in the evening. Calm and unperturbed when I read or listened to music or when I took a warm shower. Energetic and agile after I ate a large meal. Would I be able to go through with an abortion if the procedure showed a developmental abnormality?

With ultrasound guidance, the doctor inserted a needle through my abdominal wall and uterine wall to reach the amniotic sac. I concentrated on the ultrasound picture on the monitor, trying to make out the baby's shape against the grainy black-and-white background. Suddenly, the doctor stopped her probing, sterile gloves immobile against my belly. She rushed out of the room and came back excitedly with a colleague. I was frightened, thinking she had seen a problem. Instead, she told me that even though she had inserted the needle in an area far from the baby, Harlan was miraculously aware of its presence, even moving her hand as if attempting to grab the needle. "You have a really special and sensitive baby in there," the doctor said.

This turns out to be true-not that I am boasting, because all mothers think their babies are special, but Harlan is very sensitive, in terms of being quite discerning and aware. When she was only two, I was reading a book with her about a baby whale that had gotten lost. We were at a part where the baby has a joyous reunion with its parents, and she asked me, pointing to the illustration of the two parent whales, "Which one is the mommy and which is the daddy?" I looked carefully, and seeing just two gray whales of equal size, I said I didn't know. She gleefully pointed out that one in particular was the mommy. I asked her why she made this choice, and she pointed to the whale's eyelashes. "This one has longer eyelashes." I would never have noticed such a thing. Her ability to discern the most minute detail, however, means that she is able to detect my weaknesses and my lack of certainty in many matters, and as a result, she has been able to exploit them to her advantage. As you can guess, I have not been able to impart the Vietnamese cultural norms that rank the parent immutably higher than the child. She knows my ambivalence and can work to throw me off-kilter.

According to Vietnamese folklore, a child's personality is shaped by her mother's pregnancy and birthing experience. Even a tiny baby can receive her mother's memory, weaving and absorbing it into her blood, sinew, neurons, the very genes themselves. As an example, my brother Tun had struggled all his life until his death at the young age of forty. According to my mother, he suffered the effects of the war not only when he briefly joined South Vietnam's army at age nineteen, but even when he was inside my mother's womb. He had been cursed by his fetal memory of her pregnancy trauma-the bombings, explosions, and artillery shelling, which had made her anxious and jumpy. When pregnant with Tun, my mother was with my father in North Vietnam, as he had been stationed in Hng Yn Province, before the 1954 partition of the country into a Communist North and a non-Communist South. She said she could feel the baby's agitation and distress. Her anxiety and fear were in turn assimilated by the baby, calcified in his very being.

Copyright © 2020 by Lan Cao. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.