Sacred Hearts(1934)

William Eng woke to the sound of a snapping leather belt and the shrieking of rusty springs that supported the threadbare mattress of his army surplus bed. He kept his eyes closed as he listened to the bare feet of children, shuffling nervously on the cold wooden floor. He heard the popping and billowing of sheets being pulled back, like trade winds filling a canvas sail. And so he drifted, on the favoring currents of his imagination, as he always did, to someplace else—anywhere but the Sacred Heart Orphanage, where the sisters inspected the linens every morning and began whipping the bed wetters.

He would have sat up if he could, stood at attention at the foot of his bunk, like the others, but his hands were tied—literally—to the bed frame.

“I told you it would work,” Sister Briganti said to a pair of orderlies whose dark skin looked even darker against their starched white uniforms.

Sister Briganti’s theory was that bed-wetting was caused by boys illicitly touching themselves. So at bedtime she began tying the boys’ shoes to their wrists. When that failed, she tied their wrists to their beds.

“It’s a miracle,” she said as she poked and prodded the dry sheets between William’s legs. He watched as she crossed herself, then paused, sniffing her fingers, as though seeking evidence her eyes and hands might not reveal. Amen, William thought when he realized his bedding was dry. He knew that, like an orphaned child, Sister Briganti had learned to expect the worst. And she was rarely, if ever, disappointed.

After the boys were untied, the last offending child punished, and the crying abated, William was finally allowed to wash before breakfast. He stared at the long row of identical toothbrushes and washcloths that hung from matching hooks. Last night there had been forty, but now one set was missing and rumors immediately spread among the boys as to who the runaway might be.

Tommy Yuen. William knew the answer as he scanned the washroom and didn’t see another matching face. Tommy must have fled in the night. That makes me the only Chinese boy left at Sacred Heart.

The sadness and isolation he might have felt was muted by a morning free from the belt, replaced by the hopeful smiles the other boys made as they washed their faces.

“Happy birthday, Willie,” a freckle-faced boy said as he passed by. Others sang or whistled the birthday song. It was September 28, 1934, William’s twelfth birthday—everyone’s birthday, in fact—apparently it was much easier to keep track of this way.

Armistice Day might be more fitting, William thought. Since some of the older kids at Sacred Heart had lost their fathers in the Great War, or October 29—Black Tuesday, when the entire country had fallen on hard times. Since the Crash, the number of orphans had tripled. But Sister Briganti had chosen the coronation of Venerable Pope Leo XII as everyone’s new day of celebration—a collective birthday, which meant a trolley ride from Laurelhurst to downtown, where the boys would be given buffalo nickels to spend at the candy butcher before being treated to a talking picture at the Moore Theatre.

But best of all, William thought, on our birthdays and, only on our birthdays, are we allowed to ask about our mothers.

Birthday mass was always the longest of the year, even longer than the Christmas Vigil—for the boys anyway. William sat trying not to fidget, listening to Father Bartholomew go on and on and on and on and on about the Blessed Virgin, as if she could distract the boys from their big day. The girls sat on their side of the church, either oblivious to the boys’ one day out each year or achingly jealous. But either way, talks about the Holy Mother only confused the younger, newer residents, most of whom weren’t real orphans—at least not in the way Little Orphan Annie was depicted on the radio or in the Sunday funnies. Unlike the little mop-haired girl who gleefully squealed “Gee whiskers!” at any calamity, most of the boys and girls at Sacred Heart still had parents out there—somewhere—but wherever they were, they’d been unable to put food in their children’s mouths or shoes on their feet. That’s how Dante Grimaldi came to us, William reflected as he looked around the chapel. After Dante’s father was killed in a logging accident, his mother had let him play in the toy department of the Wonder Store—the big Woolworth’s on Third Avenue—and she never came back. Sunny Sixkiller last saw his ma in the children’s section of the new Carnegie Library in Snohomish, while Charlotte Rigg was found sitting in the rain on the marble steps of St. James Cathedral. Rumor was that her grandmother had lit a candle for her and even went to confession before slipping out a side door. Then there were others—the fortunate ones. Their mothers came and signed manifolds of carbon paper, entrusting their children to the sisters of Sacred Heart, or St. Paul Infants’ Home next door. There were always promises to come back in a week for a visit, and sometimes they did, but more often than not, that week stretched into a month, sometimes a year, sometimes forever. And yet, all of their moms had pledged (in front of Sister Briganti and God) to return one day.

After communion William stood with a tasteless wafer still stuck to the roof of his mouth, waiting in line with the other boys outside the school office. Each year, Mother Angelini, the prioress of Sacred Heart, would assess the boys physically and spiritually. If they passed muster, they’d be allowed out in public. William tried not to twitch or act too anxious. He attempted to look happy and presentable, mimicking the hopeful, joyful smiles of the others. But then he remembered the last time he saw his mother. She was in the bathtub of their apartment in the old Bush Hotel. William had woken up, wandered down the hall for a glass of water, and realized that she’d been in there for hours. He waited a few minutes more, but then at 12:01 a.m. he finally peeked through the rusty keyhole. It looked as though she were sleeping in the claw-foot tub, her face tilted toward the door; a strand of wet black hair clung to her pale cheek, the curl of a question mark. One arm lazily dangled over the edge, water slowly dripping from her fingertip. A single lightbulb hung from the ceiling, flickering on and off as the wind blew. After shouting and pounding on the door to no avail, William ran across the street to Dr. Luke, who lived above his office. The doctor jimmied the lock and wrapped towels around William’s mother, carrying her down two flights of stairs and into a waiting taxi, bound for Providence Hospital.

He left me alone, William thought, remembering the pinkish bathwater that gurgled and swirled down the drain. On the bottom of the tub he’d found a bar of Ivory soap and a single lacquered chopstick. The wide end had been inlaid with shimmering layers of abalone. But the pointed end looked sharp, and he wondered what it was doing there.

“You can go in now, Willie,” Sister Briganti said, snapping her fingers.

William held the door as Sunny walked out; his cheeks were cherry red and his sleeves were wet and shiny from wiping his nose. “Your turn, Will,” he half-sniffled, half-grumbled. He gripped a letter in his hand, then crumpled the envelope as if to throw it away, then paused, stuffing the letter in his back pocket.

“What’d it say?” another boy asked, but Sunny shook his head and walked down the hallway, staring at the floor. Letters from parents were rare, not because they didn’t come—they did—but because the sisters didn’t let the boys have them. They were saved and doled out as rewards for good behavior or as precious gifts on birthdays and religious holidays, though some gifts were better than others. Some were hopeful reminders of a family that still wanted them. Others were written confirmations of another lonely year.

Mother Angelini was all smiles as William walked in and sat down, but the stained-glass window behind her oaken desk was open and the room felt cold and drafty. The only warmth that William felt came from the seat of the padded leather chair that had moments before been occupied, weighed down by the expectations of another boy.

“Happy birthday,” she said as her spidery, wrinkled fingers paged through a thick ledger as though searching for his name. “How are you today . . . William?” She looked up, over her dusty spectacles. “This is your fifth birthday with us, isn’t it? Which makes you how old in the canon?”

Mother Angelini always asked the boys’ ages in relation to books from the Septuagint. William quickly rattled off, “Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus . . .” on up to Second Kings. He’d memorized his way only to the Book of Judith, when he’d turn eighteen and take his leave from the orphanage. Because the Book of Judith represented his own personal exodus, he’d read it over and over, until he imagined Judith as his forebear—a heroic, tragic widow, courted by many, who remained unmarried for the rest of her life. But he also read it because that particular book was semiofficial, semicanonical—more parable than truth, like the stories he’d heard about his own, long-lost parent.

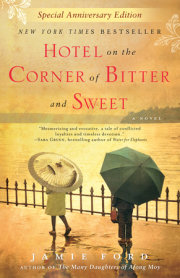

Copyright © 2013 by Jamie Ford. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.