-Dash-

December 21st

Imagine this:

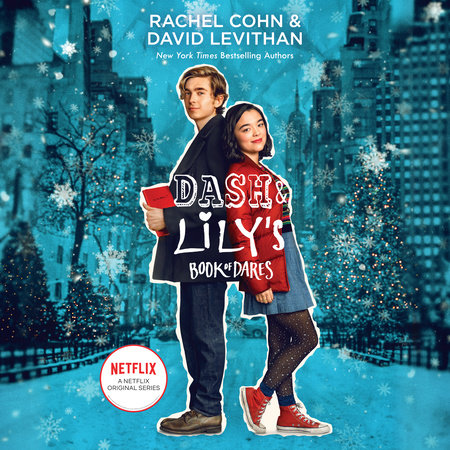

You're in your favorite bookstore, scanning the shelves. You get to the section where a favorite author's books reside, and there, nestled in comfortably between the incredibly familiar spines, sits a red notebook.

What do you do?

The choice, I think, is obvious:

You take down the red notebook and open it.

And then you do whatever it tells you to do.

It was Christmastime in New York City, the most detestable time of the year. The moo-like crowds, the endless visits from hapless relatives, the ersatz cheer, the joyless attempts at joyfulness--my natural aversion to human contact could only intensify in this context. Wherever I went, I was on the wrong end of the stampede. I was not willing to grant "salvation" through any "army." I would never care about the whiteness of Christmas. I was a Decemberist, a Bolshevik, a career criminal, a philatelist trapped by unknowable anguish--whatever everyone else was not, I was willing to be. I walked as invisibly as I could through the Pavlovian spend-drunk hordes, the broken winter breakers, the foreigners who had flown halfway across the world to see the lighting of a tree without realizing how completely pagan such a ritual was.

The only bright side of this dim season was that school was shuttered (presumably so everyone could shop ad nauseam and discover that family, like arsenic, works best in small doses . . . unless you prefer to die). This year I had managed to become a voluntary orphan for Christmas, telling my mother that I was spending it with my father, and my father that I was spending it with my mother, so that each of them booked nonrefundable vacations with their post-divorce paramours. My parents hadn't spoken to each other in eight years, which gave me a lot of leeway in the determination of factual accuracy, and therefore a lot of time to myself.

I was popping back and forth between their apartments while they were away--but mostly I was spending time in the Strand, that bastion of titillating erudition, not so much a bookstore as the collision of a hundred different bookstores, with literary wreckage strewn over eighteen miles of shelves. All the clerks there saunter-slouch around distractedly in their skinny jeans and their thrift-store button-downs, like older siblings who will never, ever be bothered to talk to you or care about you or even acknowledge your existence if their friends are around . . . which they always are. Some bookstores want you to believe they're a community center, like they need to host a cookie-making class in order to sell you some Proust. But the Strand leaves you completely on your own, caught between the warring forces of organization and idiosyncrasy, with idiosyncrasy winning every time. In other words, it was my kind of graveyard.

I was usually in the mood to look for nothing in particular when I went to the Strand. Some days I would decide that the afternoon was sponsored by a particular letter, and would visit each and every section to check out the authors whose last names began with that letter. Other days, I would decide to tackle a single section, or would investigate the recently unloaded tomes, thrown in bins that never really conformed to alphabetization. Or maybe I'd only look at books with green covers, because it had been too long since I'd read a book with a green cover.

I could have been hanging out with my friends, but most of them were hanging out with their families or their Wiis. (Wiis? Wiii? What is the plural?) I preferred to hang out with the dead, dying, or desperate books--used we call them, in a way that we'd never call a person, unless we meant it cruelly. ("Look at Clarissa . . . she's such a used girl.")

I was horribly bookish, to the point of coming right out and saying it, which I knew was not socially acceptable. I particularly loved the adjective bookish, which I found other people used about as often as ramrod or chum or teetotaler.

On this particular day, I decided to check out a few of my favorite authors, to see if any irregular editions had emerged from a newly deceased person's library sale. I was perusing a particular favorite (he shall remain nameless, because I might turn against him someday) when I saw a peek of red. It was a red Moleskine--made of neither mole nor skin, but nonetheless the preferred journal of my associates who felt the need to journal in non-electronic form. You can tell a lot about a person from the page she or she chooses to journal on--I was strictly a college-ruled man myself, having no talent for illustration and a microscopic scrawl that made wide-ruled seem roomy. The blank pages were usually the most popular--I only had one friend, Thibaud, who went for the grid. Or at least he did until the guidance counselors confiscated his journals to prove that he had been plotting to kill our history teacher. (This is a true story.)

There wasn't any writing on the spine of this particular journal--I had to take it off the shelf to see the front, where there was a piece of masking tape with the words DO YOU DARE? written in black Sharpie. When I opened the covers, I found a note on the first page.

I've left some clues for you.

If you want them, turn the page.

If you don't, put the book back on the shelf, please.

The handwriting was a girl's. I mean, you can tell. That enchanted cursive. Either way, I would've endeavored to turn the page.

So here we are.

1. Let's start with French Pianism.

I don't really know what it is,

but I'm guessing

nobody's going to take it off the shelf.

Charles Timbrell's your man.

88/7/2

88/4/8

Do not turn the page

until you fill in the blanks

(just don't write in the notebook, please)

Copyright © 2010 by Rachel Cohn. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.