We travel a lot. We regularly jump on planes to visit schools or private companies, where we give keynotes, hold workshops, teach, or simply share ideas. As we do every summer, at the beginning of June 2021, the three of us flew up to the Akwesasne territory, part of the Mohawk Nation, on the border of the United States and Canada, west of Montreal. This is an intensive program: over a five-week period fourteen young Mohawks participate in over eighty hours of intensive yoga and mindfulness training. When they graduate, they are fully trained in our Mindful Leader program-and ready to share this knowledge with other young Mohawks. That's not all: We also partnered with local community educators to provide mental health awareness training, guidance in managing a classroom, and traditional Haudenosaunee cultural education. We also teach basic skills essential for any future career path: managing finances, becoming confident at public speaking, building a strong rŽsumŽ, and resolving conflicts. These newly minted young leaders get a weekly stipend too, which helped many of them financially over the pandemic. Now these young people are employed and earning as well as learning, providing relief during the unexpected challenge presented by the COVID-19 pandemic, and allowing trainees to fully prioritize their training. There are multiple reasons we do this, but the primary one is our belief that struggling communities all over America-and the world-need to learn from each other, support each other, and work collaboratively together to design new ways of living to elevate their kids' prospects and uplift their communities in a joyful, hopeful way. At the end of the book you'll read about how we encourage our students in Baltimore to become teachers themselves or, at the very least, actively share what they've learned with their family and friends. This is very purposeful. There's only three of us, and if we had to teach every class, or mentor every kid, our program would have run out of gas years ago. Our goal is to seed communities all over the country, and eventually the world, with the techniques that will empower them to thrive and blossom in a way that conventional society, education, policing, and government policies actively squash.

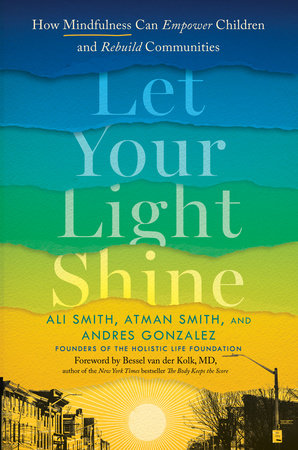

Our Uncle Will always told us that you have to "wipe the dust off, and let your inner light shine out." On an individual level this is easy to understand: If you've ever had a deep meditation, you've experienced that sensation of clarity, calm, acceptance. But it has bigger implications too: We interpret this as a light that has the potential to sweep across the world, like a lighthouse illuminating a rough sea. This light is less about us swooping in and doing the work than it is about highlighting the talent and energy and potential already in these local communities. We share our knowledge, and support-but once these groups are up and running, they need us less and less.

This trip to the Akwesasne would probably be one of our last-at least in a formal capacity-as the program was rapidly evolving into a self-sustaining model. It was primarily a working trip, but frankly after a solid year of negotiating COVID, we needed a break. It was a relief to fly north over the vast, unbroken forests of upstate New York and look down on land that-in appearance at least-comes as close as you can to uncolonized in the continental United States. Our hosts, of course, have a different perspective.

Our hosts in the Akwesasne territory are members of the Mohawk Nation. The name Akwesasne means "land where the partridge drums." And in their language they call themselves Kanien'keh‡:ka, or "people of the flint."

Like most First Nations or Native Americans, the Mohawk had a complex relationship with the early European settlers. In the 1500s, the Dutch arrived. Initially relations were good. The Dutch suggested they were the "fathers" and the Mohawk were the "sons." Unsurprisingly, the Mohawk objected to this, and said the two groups were instead "brothers." The Mohawk created a wampum belt, with two rows of purple beads that represented the Mohawk canoes and the Dutch ships sailing through the world in kinship. However, as the Dutch expanded into Mohawk territory, their relationship frayed. In the seventeenth century, Christian missionaries began to convert some of the Native tribespeople. Later, the Roman Catholics did the same. The French and English alternated between allying themselves with and fighting against the tribes. During the American Civil War, the tribes allied themselves with the British against the American settlers. When the British lost, the tribes were forced to give up most of their land, and they relocated to the land they live on now.

In the nineteenth century, Richard Pratt founded the first off-reservation boarding school for Native American children in Pennsylvania. He thought himself a good man. After all, popular opinion often called for genocide against the tribes. He merely believed that you needed to "kill the Indian, and save the man." Thousands of children disappeared, and for over a hundred years these schools insisted that the children had run away. Shortly after our visit, sonar and excavations revealed the horrific truth these schools had hidden for a hundred-plus years.

Is it surprising that we see some parallels between our world and theirs?

Throughout the twentieth century, the Mohawk had to fight to preserve what was theirs: In the 1990s things got heated when White Canadian developers tried to build a golf course on tribal lands. The mother of one of our Mindful Leaders-while pregnant with him-almost died in a shootout over it. The Canadian Army sent thousands of troops, but the Mohawk blocked off a bridge into Montreal, protesting the incursion and refusing to back down. For a minute it looked like the blood was going to flow (and two people did die). In the end, the land was purchased by the government but never actually returned to the Mohawk people.

This protest was both good and bad: It caused even worse strife and division in the tribe, and divided many people against each other, yet it also literally gave birth to the young activists we work with today. When we sit down on that green Mohawk grass with our students it's inspiring as hell: The residential schools might have tried to destroy their language and culture, even erased it from their grandparents' and parents' lives. But the young people are embracing being Mohawk fearlessly. They are learning their language, renaming themselves with Mohawk names, re-creating lost traditions, and relearning lost ceremonial practices, piece by piece. One of our teachers, Steven, moved off the reservation when he was six, with his family. He was unable to process the aftereffects of generational trauma (it was his mother who almost died at the protest) and lost years of his life to opiates. Eventually he returned to Akwesasne and struggled to get clean.

The Bear Clan Mother (Wakerakas:te, also known as Louise Herne) encouraged him to complete the six-week ceremonial Ohero:kon, or rites of passage, along with seventy other young people, eventually fasting silently and alone in the forest for four days. He told us, "Being out there you don't have your partner, parents, there is no one out there. No cell phone, no video game, no food, no water, no distractions, just you and yourself. You get inside yourself. Inside your own thoughts, your own mind and heart. You come out of this ancient ceremony with a lot of gratitude for all that you have in your life. It was a pivotal moment in my life filled with so much healing."

Steven's grandfather, even into his eighties, can't help saying the Hail Mary he was forced to learn and recite, over and over again, in the residential school, even as his soul rejects the colonizers' religion and yearns to spiritually rejoin the Longhouse, where his true ancestors are. Knowing yourself, and being free of the voice of your oppressor, is a gift no one should take for granted. Today Steven and his grandfather are learning the traditional opening address of the Mohawk culture, reclaiming their true selves word by word.

You might be wondering why a book that is mostly set in Baltimore is taking a swerve into upstate New York. Well, here's one reason: We've learned over the last twenty years that we have to roam far and dig deep to find the resources to help our kids. And equally, we've been drawn to spread what we know to other communities. Once you've seen young people's lives dramatically improved in your backyard . . . well, it's hard to keep that news to yourself. This kind of learning is always a two-way street, however. We've learned even more about how to rebuild a struggling community from the Mohawk than they've learned from us-especially in the ways that the tribe has embraced its matriarchal structure.

It's not an easy matter to travel to upstate New York in the middle of a global pandemic, but it's not an easy matter to get help from close at hand either. Sometimes you have to step outside of your world to see what is broken in it. And once you've reached a place of insight, you need to share what you've figured out. Look at our world today: We are all in varying states of crisis, all struggling to find answers to similar problems. Think how much faster we would find solutions if we shared our discoveries. We believe there's no point in solving your problems if you can't also help other people solve theirs. It's a holistic approach, and one that we've embraced for twenty years. We don't have all the answers, but we have some of them. Same with the Mohawk: they don't know everything, but what they know is valuable, and applicable to every struggling community.

The Akwesasne territory isn't some perfect place. The Mohawk deal with a ton of racism and resentment from both America and Canada. (The reservation crosses the border.) They are still recovering from their own version of Jim Crow, when Indigenous peoples were banned from places like bars and bowling alleys and discriminated against when it came to voting or getting good jobs. They are-still-confronting prejudice and discrimination when they deal with the world outside of the reservation. They had to fight two hundred years for compensation from the last time land was stolen from them and as late as 2009 Canadian border guards moderating a customs dispute interrogated every member of the tribe who left their home or attempted to return to it.

The Mohawk also have the trauma of not being heard and believed. Everyone knew that something happened to their children, but it took decades of fighting and protesting to get permission to bring ground-penetrating sonar onto church property. That generational trauma keeps on hurting: grandparents who were whipped and beaten and worse at residential schools pass on that trauma, that lack of love, to their kids and grandkids. There's sometimes too much alcohol, too many opiates, and too little affection. Yet things are changing.

The tribe are fighting like hell for their children. Sure, their youth struggle with the same existential despair of any kid growing up in an isolated or impoverished area with low wages and limited prospects. And yet the tribe has rallied together as a people. They have a deep connection to family and community, and a shared identity as a tribe and a culture. They are Mohawk first, everything else second. Within the common identity as Mohawk they have reemphasized the clan structure, giving their children an added layer of identity and belonging.

They have a connection to their heritage and their ancestors that is missing in American culture in general, but especially in Baltimore. You'll read about how Baltimore has lost all the social structures, like mentors, weak ties, social networks, and rites of passage, that are being reinvigorated in the Akwesasne territory. What's more, the Mohawk have held on to a core truth about themselves that many Americans have forgotten: at the very core of the tribe they are fully realized citizens.

The word sovereign is something we'll refer to throughout this book, but let's get something out of the way right now: We reject the way various right-wing cults or other questionable groups use the term. We don't use the word in the sketchy, fake-license-plate, "sovereign citizen" kind of way,but in a way that suggests a path forward for other struggling communities. Nor is sovereign a code for beliefs in various conspiracies or an excuse for antisocial behavior.

Our definition of sovereignty is more aligned with the kind of practices we've seen on the Mohawk reservation. They have the right to govern themselves and determine their own way of life, their own traditions and rituals, and in many cases, their own laws. They teach, feed, heal, police, and judge themselves. They often feel unloved, unwanted, and unprotected by the American and Canadian cultures that surround them. Because of this they fight every day to preserve the right to determine the ethos under which their community lives. This feels familiar to us: Our dad, Smitty, often talked about how the segregated Baltimore he grew up in was "self-contained," and how much better this version of the city was.

Part of the difference between the Akwesasne territory and society outside of the reservation is that the Mohawk embody a more matriarchal social structure. The clan leaders are women. They oversee the community and select the male members of the Haudenosaunee Council (the group of tribes more commonly known as the Iroquois Confederacy). The tribe's lineage carries on through the women. Steven is only Bear Clan because his mom was Bear Clan. The clan mothers control who leads the community in each clan. They give names out too. Steven's Mohawk name was given to him by a clan mother. When a man and woman marry, the man moves into the woman's family's longhouse; their children become members of her clan. This emphasis on the matriarchy has ebbed and flowed, but now, as the Mohawk embrace it as the means of organizing their community, their community is stronger than ever.

Copyright © 2022 by Ali Smith. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.