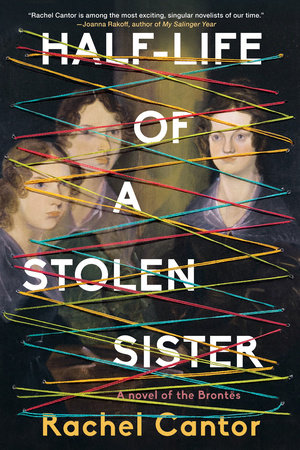

Little Mother— in which a mother dies (as recounted by Maria)

Mama teaches the difference between us.

The pillows are all behind her. Around her, left to right: Branny, the closest because he’s the Only Boy; Lotte, jostling with Bran, who’s younger by a year but bigger; Em on the end, sucking her thumb; on the right, standing, Liza, holding a broom; and me, holding Annie, who sleeps with a sucker.

Annie, she says, you will always be the baby. No matter what you do, your family will love and underestimate you.

Annie opens her eyes, drops her sucker.

Emily, you will always care more for places than people. You will go away, but you will always come back.

Em puts a blanket over her head.

Branwell, you will try with your big heart to please, but until you learn self-control, you will only disappoint.

Branny whoops and throws a soldier to the air.

Charlotte, you care most for what you do not have; learn to care for what you have, and you will be happy.

But, Lotte says (she wants so much to understand!).

Elizabeth, your needs are simple; you will be forgotten, but you do not mind.

Liza holds her broom to her chest.

Maria. Are you there? Come closer, Maria.

I lay Annie onto the bed. She crawls to Em under the blanket.

I do not need to tell you who you are: you already know. You are the Little Mother, the one who fills the spaces.

I know this. I help Mama to lift a hand to my young face.

Because Mama is poorly she no longer: makes sockdolls, cooks cabbage, buttons dresses, shouts to Branny to stop pinching, counts the teeth Liza has lost, tugs at her pinafore, chews her nails, hums music by the dishes, explains puppets, says Scoot, makes faces at Annie, makes Lotte’s little braids, makes anyone guess what’s for dinner, says poems at the fire, calms Papa, a hand in his hair.

Lotte shakes the door and shouts. She draws pictures of happy Mama, happy Lotte, in crayoned blue and red. She slides them under the door; she tries to slide a cookie, a sockdoll.

I am eight so I’m the oldest: I yank Lotte away. But Lotte is strong. Strong with fear.

She shouts: Mama needs a doll from me!

She shouts: No, Maria. No!

Children, please! Lotte wails by the water pot, placed there, before Mama’s room, for the event of fire. Branny throws soldiers, Emmy won’t nap, Annie crawls too near the stove, Liza scorches the sheets. Papa looks horrified—at all of it. He cannot read the paper for all the noise. I read to him. He shuts his eyes, his hands covering his face.

Auntie keeps saying, This isn’t how we do things.

Mama teaches us what brings us together. You are one person, she says: you have one heart, one mind, one body. If one of you fails, all of you fail; if one exults, everyone exults; if one dies, you all die. It cannot be otherwise. You can live without me, you can live without Papa, but you cannot live without each other. Remember this. Emily, do you remember? Bran? Lotte?

Mama, let me get you ice chips.

No, Maria, she says. This is important. Lotte, do you remember? Liza?

Before she got sick, Mama braided my hair; she called me Beauty and sang me songs. We are both Maria: Mama Maria, and me. But now she’s lost all reason, Papa says. Her eyeballs roll in her head and she sweats. Paddy, she says, the world is leaving me! Paddy, I am too young to die! Paddy, I fear there will be nothing after this, how can there be, if this is everything? Paddy, why won’t you hold me? Make love to me, Paddy, I am still here, I am still here!

A Little Mother does everything the mother does, but less. She does what she can. Lotte is only five. She has feelings, so I hold her.

I take Bran to the park so he can run. I tell him to throw a hundred stones into the lake. He throws as hard as he can, he makes a lot of noise, sometimes he says a bad word. He can’t count as high as one hundred, but when he gets tired I say, That’s a hundred, and he’s glad.

I take Em to the pound. She gives the dogs names and brings them treats. They climb on her face, which makes her laugh. If she laughs, she doesn’t have nightmares. If she has nightmares more than twice, I take her to see the dogs.

Liza’s nearly seven. She needs to talk. I ask her questions, about anything—the weather, what do we do to make Papa happy, is it time for washing. It doesn’t matter. When Mama got sick, Liza didn’t talk for a month; no one noticed but me.

The baby doesn’t know anything. She needs to play. I tell the others that Annie must never be sad, we must never let Annie be sad. Everyone has to make faces at baby, everyone must play games. Ring Around the Rosie, clapping games. Annie laughs. Babies need to laugh.

Mama has stopped saying she’s too young to die. She’s stopped pinching her cheeks for Papa and telling us about ourselves. I thought I understood time, she murmurs as I sop her face, but I was wrong. Pain makes each moment huge, as does relief, yet a moment is still the smallest thing we have. I want more moments, she says. I want life, I want moments, I want time! But the vastness calls me, Maria. Forgive me! You must forgive me! I am so tired.

I am tired, too.

Liza and Lotte hide in the closet, wearing Mama’s dresses and passing tea. The dresses have names we have mostly forgotten. Muslin, velvet, cocktail, other things. Auntie lets down the hems and gives them to the poor. Auntie arrived when Mama got sick. She’s here now till school starts, then she’s away. Who shall take care of them when I have gone? she asks. Paddy? Paddy? Aunt doesn’t wear dresses with names, just good dresses, serviceable dresses.

Inside the shoes you see where Mama’s toes stood. Now poor people wear Mama’s pumps, her flats and mules.

The big bed where Mama died is gone, there’s just a desk now so Papa can work, finally. Her body is with science but the important part of her’s in heaven. Papa says it’s time to forget. Aunt says, There’s baloney sandwiches. Em says, I don’t like baloney, Aunt says, Be grateful for protein.

Aunt makes sure we go to sleep and get up at the same time so we can have order. She makes meals and sews, but Aunt isn’t a Little Mother. She knows what children should become, which is little ladies and gentlemen; I know what we need now. We need to be together. I keep us together. I tell stories. About how Bran will buy us a Haworthy House worthy of the name. With six wings, servants, and pheasant for tea. Where we will have beautiful weddings with handsome swains and dresses with trains, and gossamer veils and tulips to throw.

The stories are how we know who we are, with no one left to tell us.

I will care for

all the children, I say, in our Haworthy House. Everyone’s children!

I’d like a garden, whispers Liza.

Ye shall have a garden.

I want a zoo! declares Em.

Ye shall have a zoo.

It’s bags of gold for me! says Bran.

Bags ye shall have, say I.

Annie wants lovely toys, don’t ye, Annie?

. . .

What do you want, little Lotte?

Lotte bursts into tears. I want all of it to be true, she sobs. I want all of it to be true!

We are all around her, left to right: Bran, Em, Liza, Lotte, Annabelle, and me. I hold Mama’s hand but she doesn’t squeeze. Branwell does a dance, Em gives her a flower, but she doesn’t see. She looks at the ceiling. Her lips move, but she has no words.

She is a gorgon now, spitting and choking. No one has washed her hair. She would have turned the others to stone, so I sit with her, in her room, kept dark for sleeping, for not arousing love for the world. I say, It’s okay, Mama, it’s okay. She grabs my arm but I cannot hear what she says. She chokes again, and gasps and shakes her head and dies.

Her face is white, her mouth twists, her eyes are open. She is not at peace!

Papa said there would be peace! I try smoothing her hair. I try patting her cheek as she might pat mine. I say, There, there, and think, Maybe she

is there, holding on! Maybe she doesn’t want to go! I don’t want her to go!

I look for stories to tell her about this world, to help her stay:

Liza is in the kitchen peeling potatoes, I say. She is wearing a shortish frock. Aunt says it’s too short, she’ll let down the hem soonest.

I say: Annie’s with Liza, maybe in her chair Papa found on the street. Can you hear?

Her face doesn’t move, it’s in agony!

If she goes, I want to be with her! There can be no Little Mother without Mother: we are one thing: if one of us dies, we both must die. I tie my wrist to hers. I use the elastic from my hair, I use two of them. To get close so our wrists can be tied, I go under the covers. Mama’s hip bone is sharp, her ribs are only a rack of bone, there is no softness where I can rest.

If I tell her about us, maybe she can hold on, she can hold on to me and not let go.

I whisper so only she can hear.

I say: Lotte and Bran are talking in their bunks, can you hear? Bran is dropping bombs; Lotte is getting cross.

Lunch, Auntie cries and the furniture shakes.

Kerblew, kerblew, Branny cries, the world is ending, the world is over.

Lotte says, Don’t be stupid, penguin, it’s all just as it ever was.

Copyright © 2023 by Rachel Cantor. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.