Chapter 1: The Gods of Gotham

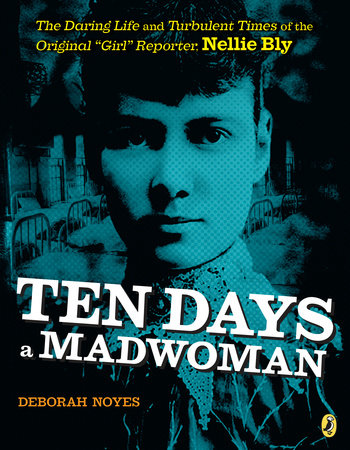

When the ambitious young reporter Elizabeth Jane “Pink” Cochran—known to her readers as Nellie Bly—left her life and family behind in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, she was confident one of New York City’s major daily newspapers would hire her at once. She had spunk. She had experience. She was fearless and eager to learn.

And she was wrong.

Nellie left her mother, Mary Jane, behind in Pittsburgh on a May day in 1887, promising to send for her when she found steady work. She stepped up onto a train and later stepped down into the most populous city in the nation wearing a flowered hat she had bought while reporting in Mexico. Like thousands of other young hopefuls, twenty-three-year-old Nellie Bly was on her own for the first time in her life.

She rented a tiny furnished room overlooking an alley on West Ninety-Sixth Street. Her lodgings were in the northernmost part of settled Manhattan, where Broadway became Western Boulevard, and the “boulevard” wasn’t paved yet. Goats wandered through, nibbling weeds in vacant lots between squat houses. It was about as far from where Nellie needed to be every day as it could get.

Her destination was Park Row, also known as Newspaper Row, a street slanting northeast from lower Broadway where newspaper offices hunkered along one side near City Hall. The trek downtown each day was epic. Nellie rode a steam locomotive a half hour south on the Ninth Avenue Elevated Railway. Then she walked east on streets where people lived grimly packed together in tenements (and were often “roasted,” as newspaper reports of the day liked to put it, in devastating blazes). Typhus, cholera, and influenza swept through the area at regular intervals. Gambling dens and bordellos thrived while the police looked the other way. Robbery and murder were commonplace, keeping city reporters on their toes. The streets were a hazard in their own right. One of thousands of horses hauling the city’s carts, carriages, hansom cabs, omnibuses, and streetcars might bolt at any moment, their transports careening into bystanders.

Nellie pounded the Park Row pavement in vain. The gatekeepers at the

Tribune, the

Times, the

Sun, the

World, the

Herald, and the

Mail and Express, who turned away aspiring reporters every day, were unimpressed by her Pittsburgh portfolio.

To scrape by that first summer in New York, Nellie wrote freelance articles for her old newspaper, the

Pittsburgh Dispatch, where she had made her start and a (literal) name for herself. They were the sort of Sunday style stories she hated, about the rage for puffed sleeves among fashionable New York women, for example.

Around the time that her money and patience were beginning to run out, the

Dispatch forwarded a letter from a young Pittsburgh woman

. An aspiring journalist wanted Nellie’s advice: Was New York the place to get a start? Could a woman writer make her mark there?

Nellie must have wanted to laugh out loud at the irony. But then an idea struck. What if she called on the editors of New York’s six most influential newspapers, on behalf of the

Dispatch, to harvest their thoughts on this very subject? She would “obtain the opinion of the newspaper gods of Gotham” and, at the same time, gain audience with the men who held her future in their ink-stained hands.

The first paper she visited was the

Sun. As she climbed the dim spiral staircase to the third-floor newsroom with its haze of cigar smoke and raucous conversation, anxious office boys darted here and there on errands. In the summer heat, men would have removed their suit coats and vests, working in sweat-stained white shirts with high celluloid collars and rolled sleeves.

Her entrance must have caused a stir. Female reporters were still comparatively rare, even in big cities like New York and Pittsburgh—Nellie proved the exception to this and other rules—and there were likely no other women in the newsroom that day when she was escorted into the office of the paper’s formidable editor and publisher, Charles A. Dana.

Between his reputation for hiring college men and his flowing Father Time beard—backed by a stuffed owl looking down from a shelf of reference books—Dana must have cut an imposing figure to a hungry “girl reporter.” But after flushing out his stance on the topic with a few questions, Nellie asked, boldly, “Are you opposed to women as journalists, Mr. Dana?”

Certainly not, he objected. But “while a woman might be ever so clever in obtaining news and putting it into words,” he said, “we would not feel at liberty to call her out at one o’clock in the morning to report at a fire or a crime. . . . [w]e never hesitate with a man.”

Women also, he maintained, “find it impossible not to exaggerate.”

Nellie soldiered on: “How do women secure positions in New York?”

She thought she saw a twinkle in his eye as he replied, “I really cannot say.”

Nellie continued along Park Row with her questions. The editor of the

Herald informed Nellie that for better or worse the public wanted scandal and sensation, “and a gentleman could not in delicacy ask a woman to have anything to do with that class of news.”

The

Times editor had never felt compelled to take up the topic with his colleagues.

Mr. Coates of the

Mail and Express called women “invaluable.” The way they dressed and their “constitution” ruled out hard reporting, but they were ideally equipped to cover stories on society, fashion, and gossip.

Women were “more ambitious than men,” the editor at the

Telegram echoed, “and had more energy,” but he “couldn’t very well send a woman out on a story where she might have to slide down a banister. . . . That’s where a man gets the best of her.”

At the

New York World, Colonel John Cockerill complained that women didn’t want to write the fashion and society stories they were best fit for. “A man is of far greater service,” he said in his forthright way, though he also claimed to have a couple of women on staff. “So you see, we do not object personally.”

After weighing the words of these six powerful men, Nellie summed up their views: “We have more women now than we want. . . . Women are no good, anyway.” Her article, “Women Journalists,” traveled out from Pittsburgh to New York and Boston and received notice in

The Journalist, a national trade magazine. Her choice of subject matter was brilliant strategy: it put Nellie Bly in the right place at almost the right time. Her moment was coming. But she had to hit rock bottom first.

Copyright © 2016 by Deborah Noyes. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.