PARADE OF MONDAYS In the early weeks of that long summer of 1997, before the bombs started going off in the capital, Cecilia came with me one last time on the Monday road trip to the village of Cojímar to help me mourn her oldest son.

As we strolled on the beach, she took my hand, and some time must have passed before I noticed, for I continued to look out to the sea and at first did not see our bodies merge in front of us as she leaned into me. It’s a sign, she told me, pointing with her other hand to our single bulging shadow. The contorted passing of a onewinged bird, she said. A sign, también, that I did not notice these things, she added.

Shadows.

A useless solitary wing.

Every Monday morning, we drove the two dozen miles from the house on Calle Obispo in Old Havana to this barren fishing village that el pendejo Hemingway had made famous with his little fishing novel, and we sat, or strolled, or looked out to the sea—the place where her son, Nicolás, had picked me up a year and a half before. We ate the lunch that Cecilia had prepared perched on a sea wall outside La Terraza, a restaurant from where dishfaced Yuma—the tourists—stared out at the crystalline sea with etherized gazes.

I thought us as hapless and doomed as the poor old man of that novel. Other times, I wasn’t that dramático. As Cecilia liked to point out: I was bored, dreaming about things that didn’t exist in the Island. They never have. Did I know, she asked, that when the yanquis had made the film of the novel with

Meester Spencer Tracy they had to go all the way down to the coast of South America because Cuban marlin rarely jump out of the water? And yanquis need that. Things jumping out. Why? I asked, playing along, not remembering if the marlin in the book jumped out. Why don’t Cuban marlin jump out? Too passive, just like the rest of us, como cualquier cubano.

I snapped my hand free and waded into the sea, the water chattering on the crushed-shells shore so that I couldn’t hear her sighs. She came there with me from the capital to appease me. Because I insisted, she reminded me. So many more productive things she could do with her Mondays. Vegetables and fruit to buy for the paladar. The earlier in the week the fresher the black-market produce, brought into the city on Sunday nights from nearby illicit farms, full crates of okra and plátanos and boniatos hidden under dusty blankets and peddled from darkened parlors—though the State had eased the restrictions on private enterprise, no one really was sure how much. Not even the inspectors from the Ministry of Agriculture knew, so they made up the rules as they went along. There were the crazy skeletal chickens to feed and their meager miniscule soft-shelled eggs to gather—flyers to get out to the hotels. Poor Juan couldn’t do it all, Cecilia said. It’s enough that he rents us a car for the day. Though it was, I knew, not rented at all, but one of the many máquinas privadas that comandante Juan owned and rented himself to taxistas in the capital to shuttle tourists around. Cecilia sacrificed her Mondays to come with me, to morbidly memorialize her dead older son, as she put it, and once here, coño, I ignored her.

I let her follow a few silent paces behind me as I trekked from one end of the rocky beach to the other, back and forth, back and forth, patrolling the shore as if not to let the endless parade of Mondays escape from us, mount a rickety balsa, and leave us forever. Soon, I feared, our weeks would be a day shorter—all the Mondays would have made their way out of the Island.

Nicolás had told me that he would leave the Island from this beach. On the day we met he told me, that he was scoping the territory, that he had stolen a formidable dinghy—those were his words, un botecito formidable—from the marina in the city where he worked as a pier scrubber and was in the process of refashioning the motor from a Russian Lada, its fan blades bent and bowed into double propellers. When I finally saw the thing, hidden in the shadows of his mother’s henhouse, it was no more than a leaky rowboat.

Noah building the ark, hidden in the shitdusty shadows of his mother’s henhouse as tourists ate their dinners a few paces away, and the starved chickens pecked at the dirt in his toenails. He was already dying the day I met him. Soon, las viejas of el Comité would notify the thugs from the Ministry of Health, who would grab him and take him in for a test and later deliver his mother a mimeographed letter on the seriousness of her son’s condition and the precautions that she and the rest of her family should take, including sterilizing any silver or plates that he might use and boiling bedsheets after his supervised visits, or better yet, reserving these things for his use only. But on the day we first met, he still thought that he had time.

So I came to this puta beach with his mother on Mondays to commemorate him, to pilfer time back, as if it were being peddled from darkened rooms with okra and plátanos.

Cecilia darted into the waters in front of me, knocked my hands from my hips, caressed my face with a calloused palm, and kissed me on the cheek. Mi mulatico tan lindo, she said and walked back to the spot on the beach where I had dropped my shirt, picked it up, and continued following me. I sat on the shore and she joined me, watching a pair of amateur fishermen on an inner-tube raft returning for the day, at first sight, their balsa not so different from the ones used by the many that had left this beach never to be seen again. They wore nothing but frayed straw hats and threadbare swim trunks that fell from their bony hips. They were young, no older than me, but they moved with the resignation of the elderly, their sleek eel-like brown bodies bent at the middle with obeisance. They had caught nothing. They tossed their empty nets on the shore and sat by them, as if mourning some giant sea monster that had beached itself. The water rose slowly around them and caressed their long still legs and their bottoms, and then it ebbed just as slowly, as if it wanted to linger there.

I kept my eyes on the boys. How does the coast guard know who is leaving and who is just fishing? I asked.

They don’t, Cecilia answered. They guess.

Maybe I’ll become a fisherman.

You’ll die of hunger, she said and added that if I stayed with her, I would never die of hunger. That she could promise. She picked up a handful of sand and smashed it on my belly.

I threw the sand back at her. Gran cosa. I’ll die an old man serving tourists boliche and arroz con pollo.

She stood up. It’s a good life, Rafa. She turned her back to the sea. Good enough.

I kept my eyes on the fishermen, intently enough for her to take it as an affront. After a while, she put the shirt back on my shoulder, careful not to brush my bare skin.

I’ll be in the car when you’re ready.

Later that night, I knew she would watch me sleep, as she had clandestinely watched us in the henhouse when I was with her son. She waited one or two hours till after I had gone to bed, after I had helped her and her Haitian-Dominican cook, Inocente St. Louis, with the prep work for the following day, snipping the dark skinny innards from shrimps, chopping vegetables, baking bread, then she sat in the shadows of the kitchen sipping spicy rum, hoping comandante Juan wouldn’t come by, hoping she could just be by herself for a bit till I fell asleep.

Mondays were the only time she did this, she would admit to me much later that summer, when the bombs forced us to remain alone in the house. Every other night there was too much to do for such boberías, the last diner would often not leave the brick-paved patio until the early hours of the morning. She had heard once from comandante Juan that the best restaurants in Paris often close down on Monday nights, so she had decided to do the same. On those nights, she watched me, watched me as she could not watch me during the day, as she could not watch me after the bustling nights feeding the hungry Yuma, watched me on the tiny bed that had belonged to her younger son, my long body rolled up into it, like a serpent into a basket. When I stirred, stretching so that my legs lengthened off the bed, the toes open like fingers, she moved back, not wanting to get caught, till my body softened again and curled itself back into the tiny bed. I was like some boneless creature in my sleep, she confessed that summer.

On Monday nights, she didn’t sleep. Sometimes on Tuesdays, while she and comandante Juan were readying for the lunch service, I said to her that she had wandered into my dreams. Comandante Juan teased me, told me boys shouldn’t dream about real women, leave that to los hombres, and he reached for her with his fat fingers like a clumsy boy reaching for a plaza pigeon.

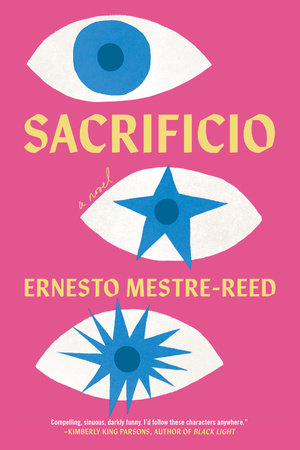

Copyright © 2022 by Ernesto Mestre-Reed. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.