1989

It’s the height of the Roaring 20 . . . 10s.

Short dresses shimmy and shine under the blindingly bright New York City lights, and our heroine sees through it all. If you follow her down the rabbit hole, you might discover an underground speak- easy where you won’t be found. Or maybe you’ll climb in the car and race off to a rollicking party on the water’s edge.

On the final night of the Red tour, Swift left the stage and chopped her folk-singer locks into a flirty flapper bob, blasting full force into new territory. She went hard into the pop sounds that influenced her earlier country albums, pumping out sparkly bop after bop. But just as the Modernism of the original Roaring ’20s had its undercurrent of satire and grim realism, 1989 bubbles with the same darkness. “Blank Space” and “Shake It Off ” poked fun at her tabloid caricature and “‘Slut!’” reclaimed it.

In many ways, Modernism has to do with rejecting traditions. Whether we’re talking about moral codes or literary forms, many of the great Modernists experimented with new styles, seeking excitement above propriety. It’s that unapologetic whimsy that reverberates in all the stacked vocals, synth beats, and clap-along choruses, making 1989 a smash hit and winning Swift her second Album of the Year Grammy. Swift writes in its liner notes that the album takes on “New York and all its blaring truth”—which means Great Gatsby mansions, but also Great Gatsby car wrecks, because the “blaring truth” isn’t all love and glamour. Truth is messy, but you have to own it to finally get “Clean.”

“Welcome to New York”

the village is aglow: The “village” here is Greenwich Village, which in the 1920s (and for much of history) was home to artists, writers, activists, and free-spirited intellectuals. The Village is a bohemian landmark, associated with countercultures and progressive ideals. It hosted an influential feminist debate club in the 1910s and became the birthplace of the ACLU in 1920. Some literary Greenwich Village residents of the Modernist era included E. E. Cummings, John Dos Passos, Robert Frost, and Kahlil Gibran.

everybody here wanted something more: This line paints a classic picture of Greenwich Village, filled with radicals and rebels who flocked to the neighborhood in pursuit of lofty ideals, individual ambitions, and freedom, often forsaking the restrictions of small-town America and/or the industrial conformity of the city at large. In the 1950s and 1960s, locales in the Village such as the White Horse Tavern, which is still open today, became gathering places for writers. Notable patrons of the White Horse Tavern include Jack Kerouac, James Baldwin, and of course Dylan Thomas (see pages 211 and 235).

and you can want who you want, boys and boys and girls and girls: Greenwich Village’s history as a haven for the queer com- munity dates at least to the early twentieth century. In the Modernist era, the Stonewall Riots were still decades in the future, but the Village provided safety and acceptance to everyone, no matter who you loved. Famous queer writers who called the Village home included New York School poet Frank O’Hara, cult-classic lesbian novelist Djuna Barnes,

poet Edna St. Vincent Millay (see page 76), and Lorraine Hansberry, the first Black woman to have a play performed on Broadway.

“Blank Space”

new money: In The Great Gatsby—a key text for this album—F. Scott Fitzgerald explores the cultural divide between “new money” (someone who became rich through their actions), and “old money” (someone from a historically upper-class and wealthy family). In Gatsby, “new money” is symbolized by the fancy new mansion, cars, and luxurious parties of Jay Gatsby. Tom Buchanan (an “old money” guy who’s mar- ried to Gatsby’s love interest, Daisy) expresses his distaste for that kind of wealth, stating: “A lot of these newly rich people are just big boot- leggers, you know.” In this satirical take on Swift’s tabloid characteri- zation, our narrator is an old-money socialite type, reading her suitor as crass “new money” to establish her dominance in the game they’re about to play.

they’ll tell you I’m insane: From whimsical Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland madness in “Wonderland” (page 97) to the more Gothic “madwoman” madness on pages 154, 161, and 167, Swift’s discography overflows with examples of women accused of insanity because they don’t conform to society’s expectations.

and I’ll write your name: The cheeky pen click is a metatextual self-reference to the author’s exaggeratedly long list of ex-boyfriends, according to the media—and also to the ever-persistent, storied threat that she’d write a song featuring them.

rose garden filled with thorns: For centuries, tortured poets have wrung meaning out of the fact that beautiful roses and sharp thorns are part of the same plant. They love it! A few examples: “A rose has thorns as well as honey” (Christina Rossetti). “He that dares not grasp the thorn / Should never crave the rose” (Anne Brontë). “Every rose has its thorn” (Bret Michaels).

“Style”

long drive could end in burning flames: Car crashes are a cen- tral motif in both 1989 and The Great Gatsby, which features three. In both contexts, we might interpret them as symbols of recklessness, passion, and danger.

James Dean daydream look in your eye: At first glance the James Dean reference seems like a style note—hot guy, leather jacket, got it—but the fact that James Dean died in a car crash due to reckless driving gives this depiction of a guy who “can’t keep his wild eyes on the road” a darker layer (and a more Gatsby-esque one—more on that in a moment).

and when we go crashing down: This reference to car crashes calls to mind The Great Gatsby—specifically, both Daisy and Gatsby’s self-destructive romance and the literal vehicular manslaughter that marks the novel’s denouement. Doomed love affairs in literature are often either compared to or marked by accidents, crashes, and confla- grations. For instance, in Romeo and Juliet (see more on page 28), Friar

Laurence compares passionate love to explosives: “These violent de- lights have violent ends / And in their triumph die like fire and powder, / Which, as they kiss, consume.”

so it goes: In Kurt Vonnegut’s science fiction war novel Slaughterhouse- Five, “so it goes” is repeated after every death as an acknowledgment that death is both inevitable and, in the grand scheme of the universe, unremarkable. We will get into this more on page 121.

“Out of the Woods”

are we out of the woods yet?: “Out of the woods” is an idiom meaning out of danger. It’s frequently used to mean someone is past the critical period of an illness or injury. Here, the phrase anticipates the car crash and hospital room imagery that follows later in the song.

the monsters turned out to be just trees: The phrase “out of the woods” illustrates a cultural tendency, reflected in literature as well as language, to envision the woods as a space of danger and uncertainty. For Shakespeare (see page 38), the woods were a place outside the con- straints of civilization—meaning those who entered the woods were unbound by rules, but also unprotected. In fairy tales, the woods are a wild place where one is likely to encounter a witch, ogre, or worse. As Swift continues to move away from her fairy tale era and starts exper- imenting with her new modern sensibilities, the monsters are revealed as fantasy, and the rules, thrown away in the woods, can be reconsid- ered and written anew.

remember when you hit the brakes too soon?: The Great Gatsby’s car crash imagery is invoked again!

“All You Had to Do Was Stay”

all I know is that you drove us off the road: And again with the car crash! This time it appears as a metaphor for someone ruining the chances of a promising relationship.

“Shake It Off”

I go on too many dates: The flip side of all these Great Gatsby car wrecks is the liberation and hedonism that was a hallmark of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Jazz Age. Here, Swift evokes the sexual and personal free- dom celebrated by the flappers of the 1920s, as exemplified by Gatsby’s aloof and independent Jordan Baker and the dissolute Gloria Patch from Fitzgerald’s The Beautiful and Damned. Like the flappers, Swift acknowledges the outdated norms she’s being judged by—in this case, the tabloid perception of her romantic life—and decides . . . screw ’em. For more on the public perception of a modern woman’s dating habits, see “‘Slut!’” on page 104.

I’m dancing on my own, I make the moves up as I go: This image of carefree dancing, without needing to be on the arm of a man or guided by predetermined steps, is the flapper ethos in a nutshell.

I’m just gonna shake: This kind of language begs for a flapper dress. There’s no better outfit for shaking off haters!

she’s like, “oh my god”: Former U.S. poet laureate Billy Collins wrote, of young women using this phrase: “Wherever they go, / prayer is woven into their talk / like a bright thread of awe.”

“I Wish You Would”

you say it’s in the past, you drive straight ahead: In The Great Gatsby, everything Jay Gatsby does is to make Daisy, who has moved forward with her life, turn back around. In “I Wish You Would,” our narrator takes on a Gatsby-esque commitment to an old love, complete with more metaphors about driving!

“Bad Blood”

mad love: Given the bad blood that follows, we could read this as riffing on the Gothic trope of the madwoman (see pages 154, 161, and 167 for more). We can also connect it to Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. Wonderland madness (see “Wonderland,” page 97) is quite proto-Modernist, as it has to do with subverting or contradicting expectations. For instance, the Cheshire Cat (see page 98) argues that he must be mad, because dogs are sane, and his behavior is the opposite of what you’d expect from a dog: “You see, a dog growls when it’s angry, and wags its tail when it’s pleased. Now I growl when I’m pleased, and wag my tail when I’m angry. Therefore I’m mad.”

and time can heal, but this won’t: If Fearless believed that “time can heal most anything,” and Red reckoned with time that “won’t fly,” but keeps you stuck in past hurt, 1989 accepts cynical disillusionment.

Pleasantries are nice, but some things are too painful to ever risk going through again. Swift adopts a new motto in these years: “You don’t have to forgive and you don’t have to forget to move on.” As the remix (and customary live performance chant) goes: “You forgive, you forget, but you never let it . . . go!”

you live with ghosts: Another very Taylor take on ghost stories— this time, the haunting is something you bring on yourself, by apolo- gizing insincerely.

“Wildest Dreams”

drive out of the city: This romantic escapade happens in a different space than the rest of our Modernist-era adventures, retreating from brutal industrialism to a more capital-R Romantic, natural, sunset- streaked setting. The need to separate from society to be together em- phasizes the forbidden love theme we see across Swift’s whole catalog (see page 107).

I can see the end as it begins: This Modernist cynicism ac- knowledges the inevitable crash and burn of a love affair, but the narra- tor chooses the predetermined cyclical fate anyway, much as in “Style.”

in your wildest dreams: Traditionally, “in your wildest dreams” is an idiom meaning that an event is outlandishly unlikely. In this usage, our narrator makes it more literal, referring to dreams of a passionate nature.

and when we’ve had our very last kiss: The “last kiss” we saw in Speak Now (page 53) returns, but this time our narrator is well-versed in endings and knows what is coming. The fairy tale “true love’s kiss” is now a momentary thrill, but always a risk worth taking.

I bet these memories follow you around: Memories are per- sonified here, sounding more like supernatural hauntings with every passing album. (See page 183 for more.)

“How You Get the Girl”

stand there like a ghost: Ghosts are a recurring motif in Swift’s canon. This moment is unusual in that the ghost is portrayed as a ro- mantic ideal—standing in the rain, being willing to “wait forever and ever,” is what makes a romantic hero. (For more on rain, see pages 36 and 45.)

“This Love”

and I could go on and on, on and on, and I will: This parallels Modernist author and playwright Samuel Beckett’s “I can’t go on, I’ll go on,” the last words of his novel The Unnamable—an expression of stubbornness that rises to the level of courage.

lantern, burning, flickered in the night for only you, but you were still gone: Is “This Love” just straight up Gatsby fan fiction? We’d argue you could read it that way. In The Great Gatsby, the green light is an electric light shining from the end of the Buchanans’ dock to guide passing boats. Gatsby gazes at the light every night across the bay between West Egg and East Egg (Long Island’s Manhasset Bay), fixating on his persistent love for Daisy despite her marriage and their long separation. Like Gatsby, this song is about rekindling old love. Our narrator deepens this reference with “This love is glowing in the dark,” as if to align herself with Jay Gatsby, hanging on to that distant hope of the flickering green light.

my ghost: Another romantic ghost, this time perhaps implying that the initial breakup represented a kind of death (see pages 34 and 231 for similar examples).

“I Know Places”

we are the foxes and we run: The fox is a recurring character in fairy tales and folktales, generally a cunning trickster; in Aesop’s fables, for instance, the fox is often trying to manipulate other animals for his own gain. But this wiliness can also make the fox a heroic figure. In Roald Dahl’s classic children’s novel Fantastic Mr. Fox, the clever fox helps his family and neighbors avoid capture (and worse) by navigating underground tunnels that let them feast and enjoy one another’s com- pany—while those who hunt them wait endlessly above.

“Clean”

gone was any trace of you, I think I am finally clean:

This moment of purification by water calls to mind ancient stories of a flood that cleanses the world of human evil (think: the Bible, The Epic of Gilgamesh, and many other examples from across the globe).

“Wonderland”*

fell down a rabbit hole: In the works of Lewis Carroll, the rabbit hole is a portal to Wonderland, a funhouse-mirror version of Carroll’s Victorian era. Wonderland has its own set of rules—perhaps as many of them as the Victorians, or the media scolds hounding Taylor Swift— but the whole world’s logic is topsy-turvy, leading to dreamlike scenari- os, silly or unsettling encounters, and a lot of misunderstandings.

what becomes of curious minds: Curiosity is a major theme in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, in two senses—curious as in interest- ed, and curious as in peculiar. It’s curiosity that leads Alice to the rabbit hole to begin with, sending her on a path she describes as becoming “curiouser and curiouser.” But giving in to curiosity (interest) can lead you to a place so curious (peculiar) that it drives you mad.

we found Wonderland: In this instance, our narrator happens upon Wonderland with a lover and gets lost there, unable to find the way home. It becomes a metaphor for a dangerous yet intoxicating rela- tionship that changes her forever. As Alice reflects during her adven- ture, “I almost wish I hadn’t gone down the rabbit hole—and yet—and yet—it’s rather curious, you know, this sort of life! I do wonder what can have happened to me! When I used to read fairy tales, I fancied that kind of thing never happened, and now here I am in the middle of one!”

Cheshire Cat smile: In case you weren’t sure whether this song was talking about Lewis Carroll’s Wonderland, our narrator directly refer- ences the Cheshire Cat, a Wonderland creature who constantly sports a wide and sneaky smile. (The cat can appear and disappear at will, but the smile disappears the slowest. As Alice puts it, “I’ve often seen a cat without a grin, . . . but a grin without a cat! It’s the most curious thing I ever saw in my life!”) Though popularized by the 1865 Lewis Carroll novel, the Cheshire cat dates back to at least 1788 as an expression for someone who shows their teeth when they laugh. (Cheshire is a region in England—the reason the cats were supposedly so happy is unclear, but it could have to do with the numerous dairy farms.)

but darling: This could be read as a callback to the Darling chil- dren in Peter Pan, the other British children’s fantasy novel that appears throughout Swift’s discography (see page 50).

we both went mad: Unable to leave Wonderland, our narrator as- similates to her new community. The Cheshire Cat tells Alice, “We’re all mad here. I’m mad. You’re mad . . . You must be . . . or you wouldn’t have come here.” (See page 167.) In the end, giving over to curiosity gives our narrator knowledge that is inescapable and drives her and her former flame to madness.

“You Are in Love”*

you keep his shirt, he keeps his word: This is an example of antanaclasis (in this case, the subtle difference in “keep” between clinging to something physically and honoring something in spirit).

I’ve spent my whole life trying to put it into words: Framed in the company of madness metaphors and war imagery, our narra- tor acknowledges her body of work, its thesis statement, and a writer’s place in history, anticipating “The Manuscript,” still ten years in the future. (See page 243!)

“New Romantics”*

we’re all bored: Ennui, or aestheticized boredom, is a key concept in Modernist (and earlier) literature and a major theme of existentialist writing.

we show off our different scarlet letters: In another play on Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter (see page 80 for more), the narrator re- configures the mark of shame as a badge of honor and flaunts it with her cohort of shamed bohemian peers.

on the road to ruin: “The road to ruin” is a common phrase that originates with the 1792 play of the same name by Thomas Holcroft. The play is a satire about an extremely wealthy family who partakes in hijinks to save themselves from financial disaster. Our narrator is living fast and careening toward whatever lies ahead with little concern for consequences, much like the characters in the play. The old Romantics (see pages 152–183, for more) loved ruins in part because they inspired the contemplation of death, transformation, infinity, and ephemerality; wealthy people of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries would even build fake ruins in their gardens to provoke such contemplation and create a romantic (and Romantic) mood.

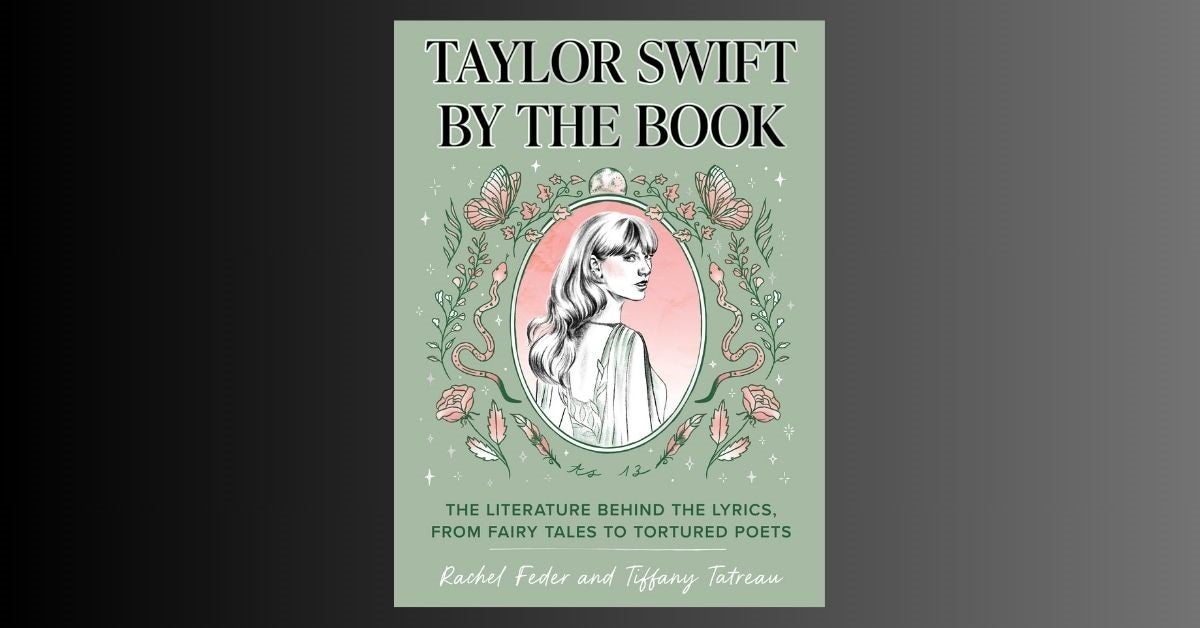

Rachel Feder holds a Ph.D. in English from the University of Michigan and is an associate professor of English and literary arts at the University of Denver. She is the author of The Darcy Myth: Jane Austen, Literary Heartthrobs, and the Monsters They Taught Us to Love; Harvester of Hearts: Motherhood Under the Sign of Frankenstein; and Birth Chart, a poetry collection. With McCormick Templeman, she is the coauthor of AstroLit: A Bibliophile’s Guide to the Stars. Rachel also edited the Norton Library’s edition of Dracula.

Tiffany Tatreau is an actor, singer, and teaching artist born and raised in Southern California. She has starred in various musicals across the country and is best known for her portrayal of Ocean O’Connell Rosenberg in the musical and original cast album Ride the Cyclone. Tiffany has a BFA in musical theater from Roosevelt University and resides in New York City. She is currently performing in the national tour of A Beautiful Noise: The Neil Diamond Musical.