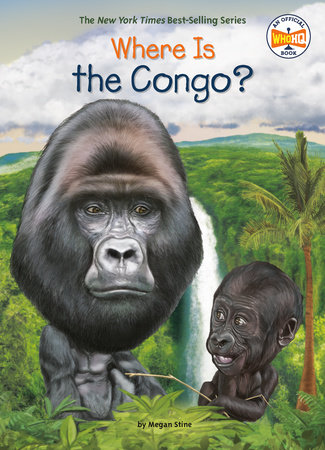

Where Is the Congo?

In 1871, Henry Morton Stanley was a reporter, roaming the world and reporting back to a newspaper in the United States. Like a lot of adventurous young men, he wanted to go exploring. He also wanted to become famous. Back then, where was the best place to go to make a name for himself?

Africa!

Africa was a huge continent with many different tribes and cultures. But very few Americans or Europeans had been there yet. Mistakenly, they thought it was a vast empty territory waiting to be “discovered.” Europeans didn’t appreciate that native peoples were already living in Africa. They didn’t know—-or care—-that Africans had a rich way of life with their own customs, laws, arts, and governments. England, France, Spain, and other countries were looking for land to grab and call their own. This hunger for new land was called the “Scramble for Africa.”

One British explorer had already been to Africa, though. His name was David Livingstone. He spent fifteen years there. Livingstone crossed the huge continent from coast to coast. At one point, he was attacked by a lion. When he came back to London, he was a hero.

In 1866, Livingstone returned to Africa to search for the source of the Nile River. This time, he was gone so long, people began to wonder about him. Was he still alive?

So the New York Herald newspaper decided to find out. They sent Henry Morton Stanley, their best young reporter, to Africa to find Livingstone.

Although the trip would be incredibly hard, Stanley wanted fame and glory. He hired 190 African men to help him on the trip. They carried his supplies, cooked his food, guided him through the jungle, and protected him from many dangers. But Stanley wasn’t grateful. He was awful to them.

Stanley whipped the Africans to make them work harder. He forced them to walk uphill, carrying heavy loads. If they tried to run away, he chained them up like slaves. Stanley thought the Africans should be grateful to him!

For nearly eight months, Stanley marched toward the center of Africa. He covered seven hundred miles, mostly on foot. He nearly died from illness along the way.

Finally, on November 10, 1871, Stanley found Livingstone by Lake Tanganyika. Livingstone was ill but refused to leave because his work was not done. He died in Africa two years later.

But Stanley’s eyes had been opened to the riches available in Africa.

Just across from Lake Tanganyika was the enormous area that would come to be known as the Congo.

Soon the Congo would become a prize jewel in the Scramble for Africa—-and Stanley would play a big role in the shameful events that happened next.

Chapter 1: The Heart of Africa

In Africa, the name Congo means many things. It is the name of a huge winding river, almost three thousand miles long. It is the name of the vast river basin—-the area around a river where rainfall collects and drains into the river. Congo is also part of the names of two modern--day countries. The larger one is called the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The smaller one is called the Republic of the Congo. When people say “the Congo,” they sometimes mean the whole enormous area around the river and the river basin in both countries. They can also mean one of the two countries—-often the larger one.

For hundreds of miles, the Congo River acts as a border between the two countries. Shaped like a curving snake or an arch, the river flows north for hundreds of miles and crosses the equator. Then it makes a U--turn and flows south, crossing the equator again before heading out to the Atlantic Ocean. Along the way, the river is dotted with waterfalls and rapids. Four main rivers, called tributaries, feed into it. The Lualaba River is the largest one.

The Congo River has many important roles to play in Central Africa. Filled with hundreds of kinds of fish, it’s a source of food. Crocodiles, too. It’s also a source of water for gorillas living in the rain forest nearby. And the river is like a highway running through Africa. For as long as people have built rafts and boats, they’ve used the river to go from place to place.

Most importantly, the Congo River acts as a drainage system for all the rain that falls in the area. And there is a huge amount of rain! The region gets about seventy--nine inches of rainfall every year. That’s almost twice as much as Seattle, Washington, which is known as one of the rainiest cities in the United States.

Why is there so much rain? Because the Congo contains the second-largest rain forest in the world. Only the Amazon in South America is bigger. The rain forest is filled with a huge variety of plants and animals. There are 2,400 different kinds of orchids in African rain forests. Orchids are beautiful flowering plants. Mahogany, ebony, and palm trees grow there, too. Some trees in the rain forest can reach 160 feet tall. That’s as tall as a sixteen--story building!

In the rain forest, it can rain for days and days at a time. The Congo—-and the rain forest—-are both near the equator, so the weather is always warm. Warm weather makes it a perfect place for plants and animals to thrive.

The river and the rain forest cover a lot of the Congo Basin. Other parts of the Congo are mountainous and jagged. And some areas are flat and covered with grasslands called savannas. There are also active volcanoes that have erupted several times in the past twenty years. Each type of landscape offers different advantages for the people living there.

But who lives in the Congo? And how did they find their way into the heart of Africa?

Chapter 2: Kingdom of Kongo

Scientists tell us that all human beings originally came from Africa.

The first people to settle in the Congo were Pygmies. Pygmy is the name for several different groups of people who are all very short. The men are less than five feet tall. Pygmies probably lived in southern Africa for tens of thousands of years before anyone else arrived. They were hunters and gatherers—-they didn’t plant their own food. Instead, they lived in the rain forests and hunted animals for their meat. They also gathered whatever fruits and berries they could find to eat.

About two thousand years ago, the Bantu people showed up. Many settled in the Congo Basin. The Bantu were hunters who also had farms. They grew corn, bananas, yams, and a root vegetable called cassava. Over time, they learned to use copper and iron tools.

As the Bantu people spread throughout Africa, they formed many small tribes. Each tribe had different customs and its own language. Even today there are more than two hundred different languages spoken in the Congo!

Today, about ninety-six million people live in the two countries that are both called Congo. About half a million of them are Pygmies. The rest belong to hundreds of different tribes or ethnic groups. Some of the largest groups are the Luba, Mongo, and Kongo. A small number of white people with European origins live in the Congo, too.

Hundreds of years ago, the Kongo people were the largest and most important group in that part of Africa. They created the Kingdom of Kongo (spelled with a

K, not a

C). The Kingdom of Kongo covered an area on the west coast of Africa that overlaps several countries today. More than two million people lived there.

The kingdom had existed since 1390. It had a ruler called the manikongo—-“King of Kongo.” It also had a capital city surrounded by many smaller towns and provinces. Governors were in charge of the provinces. Judges decided cases when people broke the law. The king collected taxes from his people. For money, they used cowrie shells—-small shells found on an island that the king controlled.

The king had a strong government and some very strict rules. No one was allowed to watch him eat. To approach the king, people had to crawl on all fours. His throne was made of wood and ivory. He carried a whip made from a zebra tail.

The Kongo people had no writing, but they had many other skills. They knew how to make copper jewelry and iron tools. They grew bananas and yams. They raised cattle, pigs, and goats.

They also enslaved people.

Slavery was common in much of Africa. Usually enslaved people had been captured during a war or had committed crimes. Sometimes a woman’s parents would give enslaved people to her husband as a wedding present. Sometimes enslaved people were set free after a certain number of years. And sometimes free people married people who were enslaved.

In 1482, explorers from Portugal began arriving in Kongo. Some were priests and missionaries—-men who wanted to spread their Christian religion throughout the world. But others were slave traders. They came to buy Africans who were already enslaved. In exchange for these human beings, they offered jewelry, cloth, and tools.

At first, the Kongo king agreed that enslaved people could be sold to the Portuguese. But over time, the slave trade got out of control. More and more slave traders arrived. They wanted more enslaved people than there were in Kongo. So the Kongo people began capturing and selling free people. They went farther inland to the jungle and kidnapped people. Then they tied them together and marched them back to European ships waiting on the coast of Africa. By the early 1500s, more than five thousand people were being sold each year. Most were sent to Brazil. By the 1600s, the number had tripled to more than fifteen thousand enslaved people per year. By then, many were sent to the British colonies in North America.

One Kongo king tried to stop the slave trade. His name was Afonso I. He ruled Kongo from 1509 to 1542. He had become a Catholic and had learned to read and write by studying the Bible with Portuguese priests.

Afonso wrote a letter to the king of Portugal, begging him to stop the slave trade. He explained that thousands of his people were being kidnapped, even his own nephews and grandsons. When the king wouldn’t help, Afonso I wrote to the pope—the head of the Catholic Church—and pleaded with him to end the slave trade. But the slave traders made sure the letters never reached the pope.

Nothing could stop the slave trade. The African village chiefs were getting rich by selling enslaved people. The white slave traders were getting even richer.

After Afonso died, the Kingdom of Kongo was much weaker. In 1665, Portugal fought a war against Kongo and won.

It was just the first step in the awful history that awaited many African territories. White people arrived. They had guns. They wanted new lands. And they intended to have their way.

Copyright © 2020 by Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.