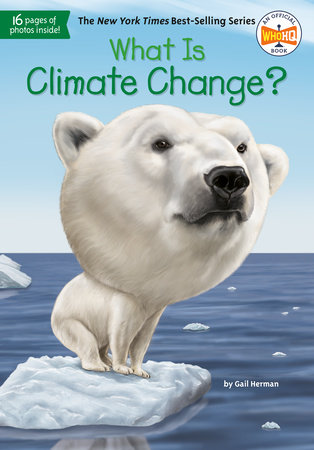

What Is Climate Change? In the Canadian Arctic, winter used to come early. By early November, temperatures dipped below zero. Snow covered the ground. Hudson Bay became covered in solid ice.

Hundreds of polar bears lumbered onto the frozen water, making their way out to open ocean. All winter long, they swam from ice floe to ice floe. They mated. They hunted and fished. There were plenty of ringed seals to eat.

When summer finally came in August, the ice melted. The polar bears swam back to land. The males play-fought. The females watched over their young cubs. Months passed. Polar bears lounged on tundra—still-frozen ground—using little energy. They waited for cold weather. They waited to go out to sea again.

Polar bears are strong, majestic creatures, standing up to nine feet tall and weighing up to one thousand pounds. They are built for the cold. Their snow-white coat is thick, with a double layer of fur. Also, a layer of fat lies just under their skin, keeping them extra warm. For months, polar bears have to live off this fat, gained from winter feedings on the ice. When they’re on land, they barely eat.

In early November 2016, the polar bears were still on land. There was no sea ice on Hudson Bay. Weeks passed. By December, there was still barely any ice at all. So the polar bears had to wait longer to return to the sea. Some paced back and forth along the shoreline. Others lay on the ground, not doing much at all.

The warmer climate affected the polar bears in important ways. In the 1980s, Hudson Bay bears were bigger and rounder, well fed. Recently they’ve been losing weight and becoming weaker. That’s because with fewer weeks on ice, their hunting season has become shorter. They have less food. In Hudson Bay, polar bear numbers have dropped. The bears have fewer cubs. And not all cubs survive.

In 2016, the water in Hudson Bay didn’t freeze until December 12. That was very late. “Sea ice is finally forming,” one scientist reported. “The polar bears are moving quickly offshore.”

Even on ice, however, the polar bears had a tougher time. There was more water between floes. The polar bears were already weakened by long months on land. And yet they had to swim longer distances to get from place to place to hunt.

Observers followed one female who had to swim nine days straight to reach an ice floe.

The Arctic—the polar bears’ habitat—is changing. Temperatures have gone up about 3 degrees Celsius (°C), or 5.4 degrees Fahrenheit (°F), since 1900.

The ice cover is shrinking, too. In 2017, it was 30 percent smaller than it was twenty-five years earlier. And each year, the remaining ice cover is melting faster and faster.

The fact is that our entire planet is getting warmer, not just the Arctic. Certain gases in the atmosphere—“greenhouse gases”—hold in heat, keeping it from escaping into space. Higher temperatures bring changes in plant and animal life. In sources of food and water. In rainfall and snowfall, floods and droughts. Habitats around the world are at risk.

It’s all part of climate change.

Chapter 1: Things Are Heating Up First of all, what is climate?

Before you dress each day, do you check the climate to figure out what to wear? No, you check the weather.

Weather changes often, sometimes in the space of a couple of hours. Climate doesn’t. Climate is the weather over long periods of time.

Scientists who study climate look at weather patterns. They need to measure temperature and precipitation (rainfall and snowfall). They’ll look to see if there are changes over thirty years, fifty years, or even one hundred years. By studying these long periods, they see whether conditions on Earth are changing.

Scientists have taken measurements from weather stations around the world, in hot places and cold ones. And the average temperatures in all these places have gone up almost 2°F since the 1880s. That may not sound like a big difference, but it is.

Earth has been having fewer cold days and more warm days. There have been fewer record low temperatures and more record highs. Even freezing-cold places are getting warmer, and not just in the Arctic. It’s also happening in Antarctica, by the South Pole. Ice caps, glaciers, and ice sheets—all forms of land ice—are melting.

When land ice melts, it runs into the sea. The additional water from the Arctic Ocean ends up flowing into all the oceans. This causes sea levels to rise around the world. On average, levels have risen eight inches since the early 1900s and about two inches since 2000.

Again, that doesn’t seem like much. But these changes in the Arctic have an impact on weather patterns for the entire planet. It’s like a teeny, tiny spark that sets off a fire.

In Alaska, coastal villages have already seen dramatic change. Homes are threatened by flooding and erosion—that’s water wearing away the shoreline. Sea ice is melting. So is permafrost, the permanently frozen soil just under the ground. The permafrost even feels different. It’s springy, which causes houses to collapse into the water.

The people of an island town called Shishmaref have voted to move their village. It will take years and much money to do it. But the people are ready. “The land is going away,” one man explained.

What about places that are already hot? Higher temperatures are bringing changes in these areas, too. Land is drying out. Water sources are dwindling.

In Africa, Lake Chad sits on the edge of the Sahara Desert. Millions of people in Chad, Cameroon, Nigeria, and Niger relied on the lake—once one of the largest in Africa—for drinking water, fishing, and farming. But there is hardly any lake left. Since 1963, Lake Chad has lost nearly 90 percent of its water. It has shrunk because higher temperatures made the water evaporate at a faster pace. (Overuse is another reason. After all, the lake provided food and water for so many.)

So how do climate scientists explain this global warming? It all starts with greenhouse gases in our atmosphere.

Copyright © 2018 by Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.