TABERNACLE Since they shared the samemonogram, JimCrow & Jesusoften found themselvesgetting the other’s dress shirtsback from the wash.This was after Jimhad made it big& could afford suchsmall luxuries. He& Jesus mostly metSundays in churchwhere Jesus came for the singingbut stayed for the sermon& to see whether the preacherever got it right.Jim, you guessed it,came for the collection plate& after stayedfor the hotplates of the LadiesAuxiliary (no apostrophe).To onefolks prayed,the other they obeyed.

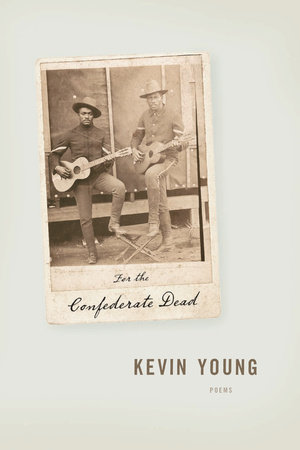

FOR THE CONFEDERATE DEADI go with the team also. –WhitmanThese are the last daysmy television says. Tornadoes, morerain, overcast, a chanceof sun but I do nottrust weathermen,never have. In my fridge onlythe milk makes sense–expires. No one, much lessmy parents, can tell me whymy middle name is Lowell,and from my tableacross from the ConfederateMonument to the dead (that palefinger bone) a plaquedeclares war–not Civil,or Betweenthe States, but for SouthernIndependence. In this café, below sea- and eye-level a mural runsthe wall, flaking, a plantationscene most do not see–it’s too mucharound the knees, heighthof a child. In its fields Negroes bendto pick the endless white.In livery a few drive carriageslike slaves, whipping the horses, facesblank and peeling. The old hotellobby this once was no longerwelcomes guests–maroon ledger,bellboys gone butfor this. Like an inheritancethe owner found itstripping hundred years(at least) of paintand plaster. More leaves each day.In my movie there are nohorses, no heroes,only draftees fleeinginto the pines, some fewwho survive, gravelywounded, lyingburrowed beneath the dead–silent until the enemybayonets what is believedto be the lastof the breathing. It is getting later.We preparefor wars no longerthere. The weatherinevitable, unusual–more this time of yearthan anyone ever seed. The earthshudders, the air–if I did not knowbetter, I would thinkwe were living all alonga fault. How lateit has gotten . . .Forget the weathermanwhose maps move, blink,but stay crossedwith lines none has seen. Raceinstead against the almostrain, digging beside the monument(that giant anchor)till we strikewater, sweatfighting the sleepwalking air.

POSTSCRIPTSThe world is a widow.Storms surround us, areasof low& high pressuremoving through–should be gone tomorrow.Rain from the skylike planes.We pull ourselves upfrom bedor death, wanderstreets like ghosts,lost guests.Everyone’s a townwith the shops shuttingdown, no hoursposted. Even the radiostays closed–only newsor fools stillbelieving love.Traffic that won’t move.In the crossing, a white hearsehanging a left.I want to be that womanjust ahead, tapping her footout a car window, bare,in time to a musicI can’t quite hear.

September 2001

Copyright © 2007 by Kevin Young. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.