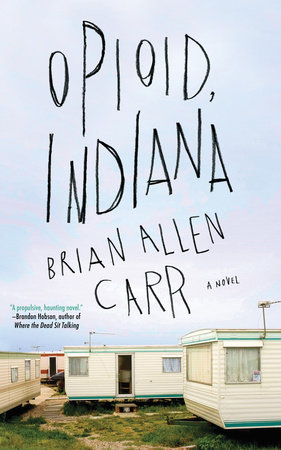

I’m from Texas, but most of this story takes place in Indiana, where the winter weather sits like iced gray vomit on the cornfields. Every restaurant serves fried pork sandwiches. Half the men over thirty-five are so numb on opioids you could win a bar fight just by swinging a dead cat over your head and running in circles. Not that I can get into a bar. Shit, I’m seventeen.

In Indiana kids my age vape with nothing in it but flavor. Might as well eat candy fog. I’m not the biggest fan of getting fucked up, but if I’m doing something, I’m doing it for real. None of the Mexicans I knew in Texas vaped and I never chilled with whites before moving to Indiana. They’re fine. I’m one of them. But I’m not gross. I don’t sit around eating food-stamp Frosted Flakes while ragging on black folks because they’re looking for handouts. I don’t scream “Build the Wall” every time I hear a language other than English.

Whites aren’t supposed to talk race, and I didn’t realize that until I came here. Back home, almost everyone’s Mexican American or Mexican Mexican, so we’d talk about being white all the time, because my non-white friends were curious, and mostly back home when you talked about being white, you’d talk about how mean white people’s parents are. Mexican kids never get told to leave home. They can live in converted garages until they’re seventy-five years old and not a single soul would judge them.

If you’re nineteen and white and not paying a grand a month for an apartment, you’re a piece of shit. Whites can’t keep long in their parents’ nests. Gobbling up their parents’ food. Watching cartoons on their parents’ cable.

White folks also get bad sunburns, and that was the other thing my friends would ask about. I’d show up with pink cheeks on some Monday and they’d ask if I was wearing makeup.

Maybe I didn’t belong in South Texas. It’s a place mean with heat, but Mexicans seemed at home there, standing on that thorny land with their backs to the sun. Singing hymns to Quetzalcoatl in nearly lost native languages. Hoping for rain. Healing off medicine made from plants. Rubbing eggs over babies’ bellies to cure them of fever.

Indiana is mean with cold, but whites go wrong here too. They get too doughy. They get that Mountain Dew mouth. Like they brush their teeth with candy. Like the only time their hearts race is when they’re screaming at news channels. Popping pills to catch boners. Popping other pills to get their dicks back to soft. And when I saw these white boys in Indiana vaping nothing but flavor, it about made me sick. Might as well boil some water, huff the steam and then chew gum. Jesus, take control of your dick and be somebody.

All that said—Texas is the greatest country on the planet and Indiana is the greatest state in the nation. Honestly, in some ways these Hoosiers are just Mexicans with white skin. They love cars and America and guns and the military, and that’s just like Mexicans. And both old whites and old Mexicans are racists too.

Here’s a story: I had an across-the-street neighbor back in McAllen, Texas, who used to mow lawns. He was ninety-four years old. I swear to God. He’d been in the military and he was as skinny as a suit on a coat hanger, and one day he came to my house and knocked on my door. I can’t remember his name but it might’ve been Emilio. We talked all the time, but I only called him “Sir.”

He was at my door and it was like this: “Hey, Riggle.”

That’s my name, and I was like, “Hey, Sir.”

“Look,” he told me. He unbuttoned his shirt and widened his eyes. They were like gray fried eggs. A few different lifetimes swam in the color of them.

“What’s that?”

He had a bandage on his chest that he pulled back and it sort of flapped open like a hanging white tongue to reveal a stapled-shut stretch of Sir’s newly shaved chest. “Open heart surgery,” he said.

“What the hell?”

“Touch it,” he told me. It was like a dare. Like if I didn’t I could never be a man, and he gazed away into some distant and masculine abyss. I laid my hand on the bumpy scar. “Quadruple bypass,” he said, and my hand seemed to absorb some of the energy from his healing. “Do you have any beer?” He licked his lips and buttoned his shirt back. “The wife won’t let me buy any, ever, since the operation.”

My hand was still sort of tingling as I processed the request. “Should you be drinking?”

His mouth tightened. “Are you a doctor?”

I sniffed my hand. “Nah.”

“Then do you have any beer?”

I always had beer. My guardian would buy cases of Lone Star and I’d pinch a few whenever, and hide them

at the back of the vegetable drawer because my guardian was a fat ass. “Meet me out back.”

I lived backed up to an alley, and we stood out there on the asphalt in the heat of September sipping beers and he told me his tales as we both sweated in the sun.

“When I was about your age,” he said, “I joined the army. I was stationed in El Paso.” When he said the words El Paso, it was like the ghost of every Mexican Christmas Past came dancing a hat dance from out his throat. A tumbleweed drifted across a desert highway. Somewhere, a whip cracked. “There was a movie theater there,” Sir said. “Me and all the boys would go.” He took a long swig of his beer. Swallowed. Looked down the alley. “We were Mexican. Had to sit in the balcony. Can you imagine? Had to sit up there in our US Army uniforms just because our skin was brown.”

There was terrific silence in the heat of the alley. You could smell the asphalt roads turning back into tar.

“That’s terrible, Sir, I’m sorry.”

“You think we’ll ever have a Mexican president?” he asked. “In my lifetime?”

“Dunno. I hope so. Maybe. Women ones too.” This was back when Obama was still president, before we knew Trump would be next.

“Hm,” he said. “Just makes me mad we had a monkey before a Mexican.” He drained his beer in one final and dramatic chug, and he chucked the empty can at the asphalt and it tipped and tapped down the way a bit until it came to a rest, glinting in the September sun. “Thanks for the drink,” he told me. He pounded his chest with a fist. “I gotta mow some lawns.”

He walked off and I drank the rest of my beer and kicked at weeds that grew through the cracked-open asphalt and thought to myself: Did Sir really call Obama a monkey? And in the context of that story? Like, in that theater in El Paso, where would Sir have had Obama sit?

Here is something that should shock you: in Indiana, there are Confederate flags everywhere. I mean, that’s an exaggeration, but there are more than in Texas. And that is not an exaggeration. These corn growers fly the bars and stars all over. Two blocks away, this old dude’s got a truck that has

Heritage Not Hatred painted on his tailgate above a rendition of Old Dixie, and that shit just eats me up. Whose heritage, struggler?

When I was growing up in Texas, I was always under the impression that the Confederate flag was something white Texans should be ashamed of. I mean, rednecks flew them, but rednecks would sneak into goat fields on moonlit nights to sex the doe goats. Call that losing your hick virginity. I always wondered what that smelled like. Out there in pasture. Your Wranglers tucked into your

Red Wings. Thrusting back and forth as the messy she-thing bleated in the dew-wet grass.

These Hoosiers fly them bars and stars like they’re paying homage to their forefathers. Their forefathers were heroes. My forefathers were Twilight Zoners. They wanted black men to pick their cotton and black women to swallow their seed, and they wanted to repay that work and humiliation with more work and humiliation. Why would you take up a thing I’m ashamed of from my past and claim it as your own?

I think it’s a trick. It’s like someone said, “So long as you fly this flag, the worst thing you’ll ever be is a sharecropper.” But I don’t buy it. You can’t get less slave. You can get less rich and you can get less poor, but you are a slave or you are not.

Right now I’m staying at my uncle’s place. My last guardian, my dead father’s cousin, got tired of me stealing his beer, and that’s why I’m in Indiana, and that’s why I’ve seen snow. Hell, some’s falling right now. It drops like goose feathers and lands like white scabs on the skin of the world. The first few times I saw it, I got excited. Now it makes me depressed. The days have been gray for months. Schools across the country keep getting shot up by angry boys who can’t get their dicks wet, and the president’s always tweeting nonsense, and my uncle’s girlfriend, Peggy, drives me crazy. In the sex way.

My uncle’s been gone a few weeks, and Peggy is in the living room singing along to Brandi Carlile. I’m seventeen. I’m from Texas. I’m a struggler. Peggy is like, “Wherever is your heart I call home,” and I’m like—my heart is in my chest and I’m in the next room yearning and last she talked to my uncle, he was off to binge-snort meth or drop low on Oxy. Off to hunch somewhere and wait for the firemen to hit him with Naloxone or maybe go out to chop down trees to cure his meth boredom. Meth heads will do it. Meth heads will do all kinds of weird meth shit. Hell, if we could just get honest, America could be the cleanest place on earth. You could have hordes of roving tweakers turning in sacks of litter they found on the highways for lines of meth. You could drop them in the ocean with snorkels to pick plastic off sea turtles’ snouts. Surfacing every so often to smile their rotten teeth and hand over garbage and get more crank.

Peggy’s the type of woman who falls in love for pain. Women do it. I know that around the country right now women are trying to change things, and I get it. Hell, a time or two I should’ve kicked my uncle’s ass just on account of how he treated Peggy. But those times he was on meth. If he’d have been on painkillers, I might have thrown hands at him. But you can’t fight someone who’s on meth. They don’t feel a thing. If you’re on painkillers you can get your ass kicked. If you’re on meth you’re invincible.

But women like Peggy aren’t always like the women on the internet. I’ve got 174 Twitter followers, which isn’t much but I don’t have unlimited data, and I read my feed and I see what the people I follow post. But girls still date boys who are mean to them. Maybe not the honors girls or athletes or cheerleaders. The regular girls. The ones who are just there. And I guess all of that is fine. Do what you want. But don’t be surprised when illogical shit leads to illogical shit.

Peggy will say she wants to be treated good, but she gave her heart away to a druggie.

I don’t want to tell you the name of the town I’m in, so we’ll call it Opioid, Indiana, and it’s near Indianapolis, and I suppose it’s home to me.

Copyright © 2019 by Brian Allen Carr. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.