INTRODUCTION

María del Carmen Ariet García

Che Guevara Studies Center, Havana

The publication in this book of such well-known and at the same time such unique works by Ernesto Che Guevara has not been done solely for literary interest but in order to bring together his ideas, reflecting certain common themes and objectives. We also wanted to demonstrate the continuity between these works and earlier writings — many of which were conceived in different contexts but which nevertheless follow a similar line — and to indicate how Che was able to merge philosophy, politics and economics in his all encompassing, coherent revolutionary vision.

A detailed reading of these works reveals the scope of Che’s decisive theoretical contribution in the historical period leading up to what could be described as his international phase. These works are, above all, the culmination of a method of work in which theory was used to solve concrete problems, a process that is not apologetic or dogmatic but rather marked by a revolutionary ethic that is both humanist and Marxist. Che Guevara was clearly “ahead of his time” as his ideas and his struggle strike a chord in the current search for global justice.

Che was a Marxist thinker who emphasized practical action. He set out to generalize his revolutionary experience, using the example of the Cuban Revolution and his experiences as a leader of that revolution to inspire other revolutionaries, especially those in the Third World. Che’s legacy of speeches, conference papers, essays, articles, televised talks, interviews and letters truly express the relationship between his daily actions and his final objectives, and show how he transformed theory into a viable instrument for the revolutionary movement that would ultimately help bring about the full emancipation of humankind.

The study of the development of Che’s thought cannot be divorced from the historical context in which many of his ideas first emerged — a unique and significant period. The 1960s have been labeled as “the transcendental rebellion between two existing powers of domination” and by the force and prevalence with which rebellious struggles emerged. Possibly the most significant of these struggles took place in the Third World, best symbolized by the Cuban Revolution and the influence it had on the revolutionary movement of that time.

The impact of Che’s death in October 1967, and its repercussions for an entire generation of people fighting for social change, is highlighted by the Nobel Prize winner José Saramago, who recalls:

The clandestine portrait of Ernesto Che Guevara came to the unhappy Portugal of Salazar and Caetano. His image was the most celebrated of all, a portrait in striking tones of red and black. It became the universal image for the revolutionary dreams of the world. In spite of the historic setback of the collapse of the socialist bloc, Che’s thinking and example have been revived as a way of reestablishing continuity with genuine revolutionary socialism, which strives for full national liberation as part of a project of social change.

By focusing on a particular historical epoch, it is possible to gloss over important facts. Without losing perspective, the negative and positive aspects of that period need to be assessed.

In understanding the past, we can see the objective need for such a sharp speech as that given in Algeria on February 24, 1965, at the Afro-Asia Economic Seminar, a speech which Che’s detractors have said showed his break from the Cuban Revolution. In reality, this speech included nothing that Che had not previously said about the nature of capitalism and the revolutionary struggle that would open the way for a new, socialist society.

In “Socialism and Man in Cuba,” the letter sent to the Uruguayan journalist Aníbal Quijano, director of the weekly publication Marcha, Che felt the need, among other things, to summarize his analysis of the Cuban Revolution, its experiences and its important lessons for other countries embarking on similar struggles in the future. This historic letter — written just days after the speech in Algeria and on the eve of his incorporation into the revolutionary struggle in the Congo — discussed the question of profound social change and why certain faults and inconsistencies occurring within the socialist countries would affect the process of constructing socialism.

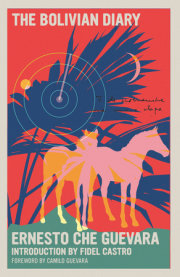

“Message to the Tricontinental” is one of Che’s more well-known works, published for the first time on April 16, 1967, in very different circumstances from the other pieces included in this book. By this time Che was already fighting in Bolivia. It is included here to illustrate the continuity of Che’s principles. Written in the context of struggle, he presented an analysis that responded to the issues being debated in a world full of contradictions and inconsistencies. In great detail, he outlined the tactics and strategies that should be followed in revolutionary struggle in the Third World.

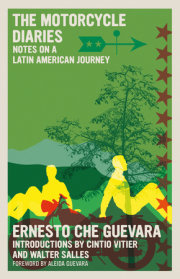

Detailed study of each of the texts included in this book shows that they form the basis of Che’s philosophical, economic and political strategy for a tricontinental revolution. There is an historical vision that goes beyond the immediate and under which lie the foundations of a larger project. For Che, this process began with his individual experience as a young activist that later led him to become part of a collective fight when he decided to join the revolutionary struggle in Cuba; this would later extend to his participation in the struggles of other lands.

It is essential, as part of this analysis, to emphasize that Che’s intellectual development was concretized through a political practice that flowed from his ideals. Central to Che’s thought and actions was a deep-seated humanism, which guided his Latin Americanism and which led him to a deeper sense of Marxism, along with a sharp anti-imperialism. This was what brought him into the Cuban Revolution and later shaped his ideas about revolutionary struggle in the Third World, guided by a revolutionary ethic as a weapon of combat and the spiritual striving for the liberation of humankind.

It is this underlying ethic reflected in Che’s theory and practice that is the basis for the widespread acceptance and support of his ideals in the modern world. It makes his vision for global justice far reaching and proves that — in terms of theory — Che was ahead of his time…

Copyright © 2024 by Ernesto Che Guevara. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.