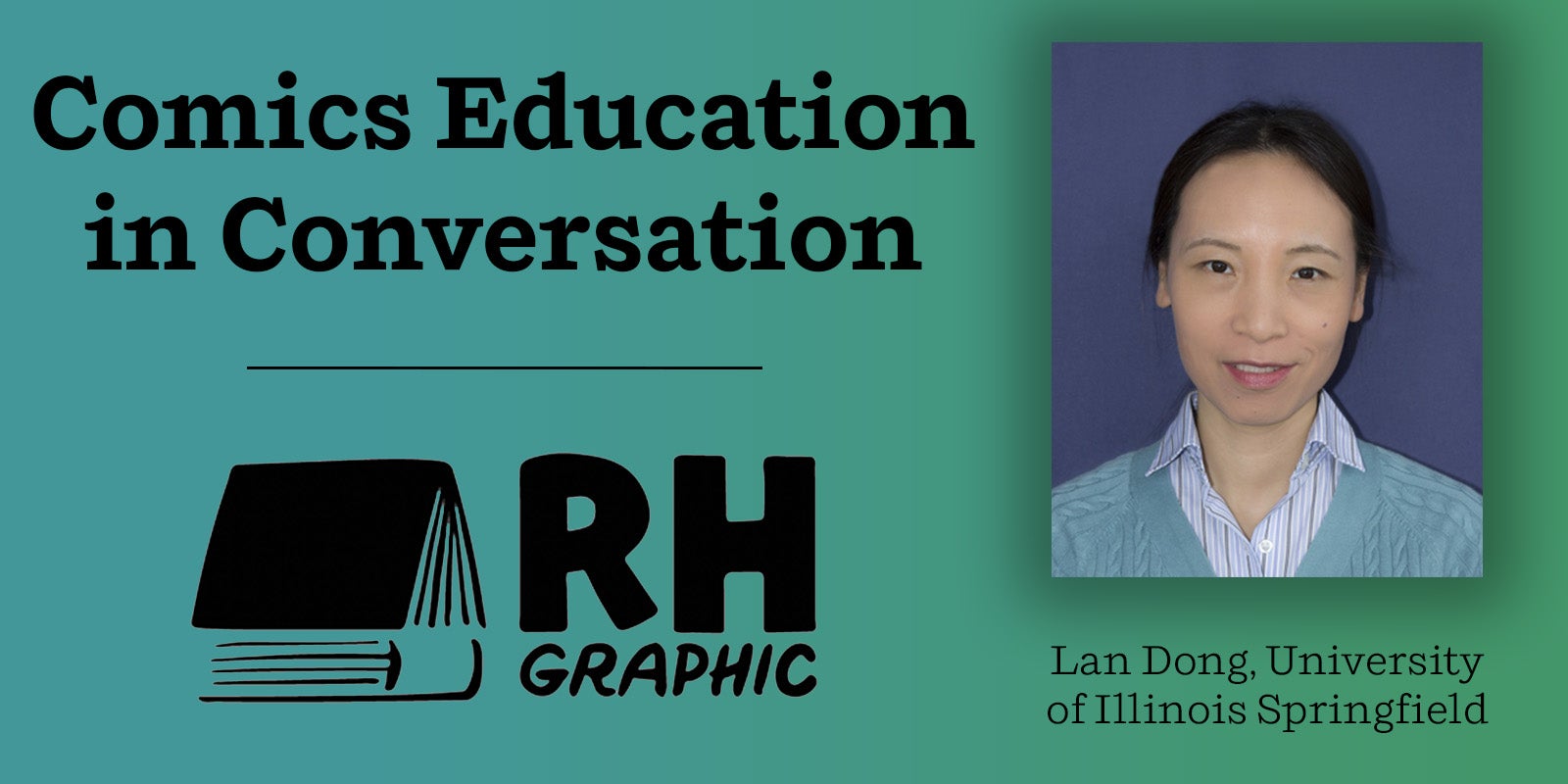

Lan Dong is the Louise Hartman and Karl Schewe Endowed Professor in Liberal Arts and Sciences and Professor of English at the University of Illinois Springfield. She teaches Asian American literature, world literature, comics and graphic narratives, and children’s and young adult literature, and has published numerous articles and essays in these areas. She is the author or editor of several books, including: Reading Amy Tan, Mulan’s Legend and Legacy in China and the United States, Transnationalism and the Asian American Heroine, Teaching Comics and Graphic Narratives, Asian American Culture: From Anime to Tiger Moms, and 25 Events That Shaped Asian American History.

How did you get started reading comics?

I remember reading Herge’s The Adventures of Tintin, Zhang Leping’s The Adventures of Sanmao the Waif, and a lot of pocket-sized Chinese picture-story books (“Lian huan hua”) as a child. When I started graduate school in the US, I began reading Art Spiegelman, Marjane Satrapi, Lynda Barry, Neil Gaiman, Allan Moore, Joe Sacco, Osamu Tezuka, Hayao Miyasaki, political cartoons about immigration and exclusion, and other comics and graphic narratives.

Then – how did you get from your first comics-reading experience to doing academic work about the medium?

That transition has a lot to do with teaching. The first graphic narrative I adopted for a class was Art Spiegelman’s Maus A Survivor’s Tale. I taught it in a Comparative Literature course when I was a graduate student instructor at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst. Since then I have used a variety of comics, manga, and graphic narratives in different courses when I can. After I started working at the University of Illinois Springfield, some of my students asked me to develop a course on graphic narratives. So I did, and that course has a focus on global awareness. Preparing for teaching and exploring various materials and theories together with students led me to the field of comics studies.

Have you seen a change in the academic (and/or popular) reception of comics and graphic novels over the course of your career?

Yes, I have seen a change in both the academic and popular reception of comics and graphic narratives. More instructors use comics and graphic narratives in their classes across different disciplines and interdisciplinary fields; graduate students choose comics and graphic narratives as the center for their thesis projects; comics-related presentations, panels, and roundtables become fairly common at various conferences; publishers establish series and programs focusing on publishing graphic narratives and comics studies. We have seen an increasing number of publication in terms of comics and graphic narratives for various age groups as well as scholarly studies in journals and books.

You’ve done academic work specifically focused on kids and YA graphic novels. What’s exciting about that space?

That space is suitable for different age groups, not only for children and young adults but also for educators, librarians, parents, scholars, etc. It is a rich area for us to explore the importance of visual literacy and critical thinking, the educational values of comics, the different ways of engaging readers through multimodal texts, and the similarities and differences between comics and other media that embrace visual elements. Like comics, children’s and young adult literature has also been marginalized and undervalued historically. Things have changed but there is still a lot of work to do.

You’ve edited a book about teaching comics. What have you found about how people are teaching (and learning) about comics?

The collection Teaching Comics and Graphic Narratives began with my curiosity to find out why and how other people teach comics and graphic narratives, particularly in college and university courses. It started with a panel for the Modern Language Association’s annual convention more than a decade ago and morphed into a project bigger than I had planned, partly because I found a group of like-minded people. I learned a lot about different practices, pedagogies, and strategies of teaching comics in a wide range of disciplines from a diverse group of instructors in the US and other countries.

There’s been an ongoing discussion about the importance of diverse representation in comics, and diverse authors creating comics. How is that reflected in your work on Asian American creators?

I am glad to see more diverse representation in comics and the increasing number of scholarly publication on the underrepresented and the marginalized in recent years. Comics production and studies in the US have made progress towards inclusion, but there is still a long way to go. A lot of the work I have done in comics studies connects historical representations of Asian immigrants and Asian Americans with contemporary work by Asian American artists and writers, reminding the reader the importance of representation and the complexity of stereotyping.

What are you working on now?

One project I am working on examines how comics can disrupt the superhero genre through humor and exaggeration, how visual markers such as costumes, insignias, and skin color bear witness to the industry’s gradual progress in representations of racialized superheroes in the US, and how comics can empower Asian American communities and become an expression of Asian American history and culture. Another project I am working on looks at how graphic narratives at the intersection of personal stories and the socio-political history of Vietnam, France, and the United States can draw a collective memory without erasing each individual’s unique experience.

Favorite or new graphic novel recommendations?

There are many! A few recent graphic narratives I would recommend include: Vivian Chong and Georgia Webber’s Dancing after TEN, Lisa Wool-Rim Sjoblom’s Palimpsest Documents from A Korean Adoption, Thi Bui’s The Best We Could Do, and Mariko Tamaki’s Laura Dean Keeps Breaking Up with Me.