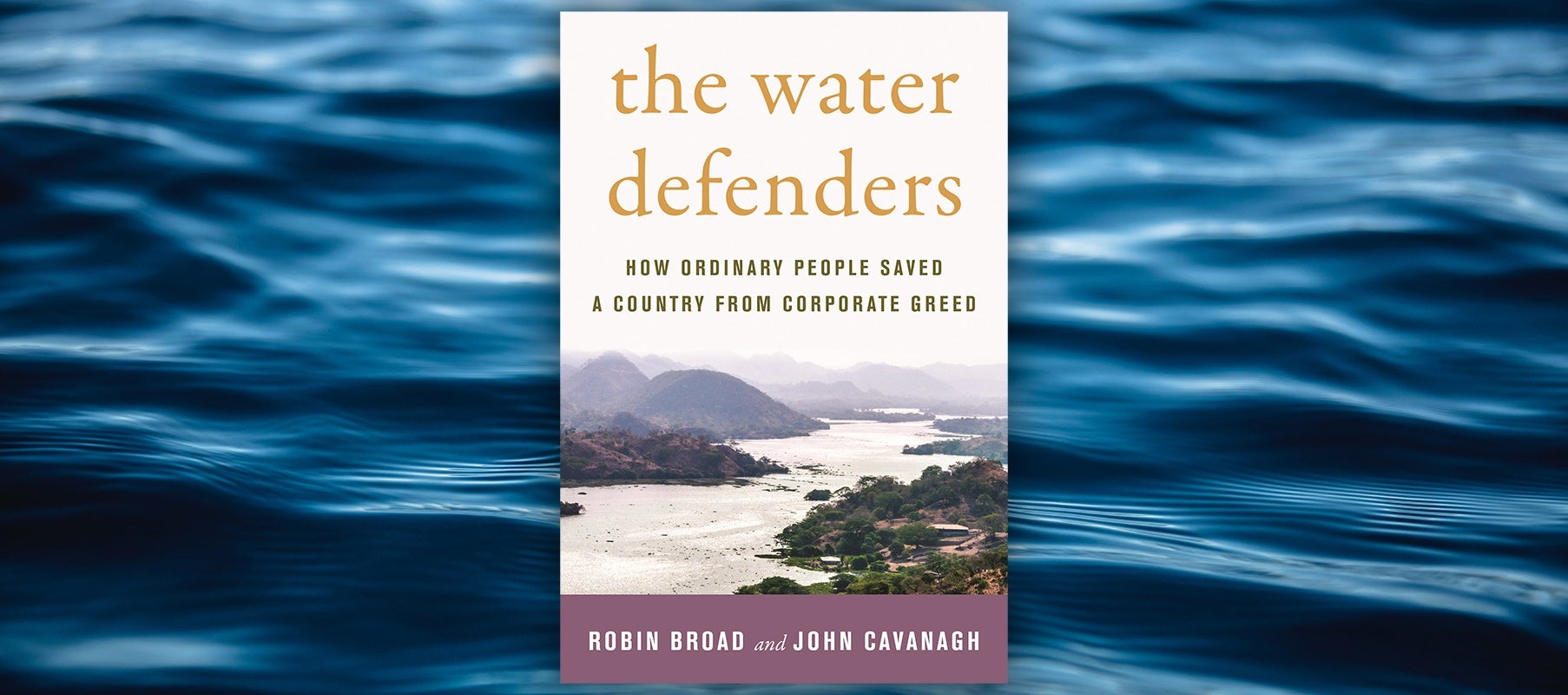

Left: Robin Broad; right: John Cavanagh

In the early 2000s, many people in El Salvador were at first excited by the prospect of jobs, progress, and prosperity that the Pacific Rim mining company promised. However, farmer Vidalina Morales, brothers Marcelo and Miguel Rivera, and others soon discovered that the river system supplying water to the majority of Salvadorans was in danger of catastrophic contamination. With a group of unlikely allies, local and global, they committed to stop the corporation and the destruction of their home.

Robin Broad and John Cavanagh tell their David-and-Goliath story of winning two history victories in the face of seemingly insurmountable odds in The Water Defenders: How Ordinary People Saved a Country from Corporate Greed. Beacon Broadside editor, Christian Coleman caught up with Broad and Cavanagh to ask them what inspired them to write the book and what its message holds for this year’s World Water Day.

Christian Coleman: What was the inspiration behind writing The Water Defenders?

Robin Broad and John Cavanagh: This book is about two of the most unlikely and inspiring victories that we’ve ever witnessed or had the privilege to be part of. That these wins take place in a poorer country, one that the United States and global corporations have exploited for decades, makes the wins even more remarkable. As we celebrated the victories, we realized that by sharing the story of these wins in a narrative nonfiction book, we could also share this sense of hope with readers, including readers who may have given up hope in these challenging times.

If ordinary people can stand up to the economic and political power of global corporations in El Salvador and win not one, but two, improbable victories, imagine what people can do elsewhere. So too did we want to cull the lessons of these victories for fights in other countries that people are waging against the likes of Amazon, Walmart, ExxonMobil, Facebook, Pfizer, and Wells Fargo.

CC: You’ve been involved in the Salvadoran gold mining saga since 2009. Tell us about how you got involved?

RB and JC: Truly, it was serendipity. John’s organization, the Institute for Policy Studies, selected a national network of Salvadoran water defenders to win IPS’s prestigious annual human rights award in 2009. Five water defenders were to come to Washington, DC, in October 2009. But three months before the award ceremony, we received the shocking news that one of the five, teacher and cultural worker Marcelo Rivera, had been brutally assassinated. We were horrified.

Marcelo’s younger brother, Miguel, came to Washington, DC, in his place to accept the award. And after the ceremony, he respectfully asked for help. The mining corporation had initiated a legal case against El Salvador in a secretive tribunal at the World Bank Group in Washington, and the water defenders knew little about this venue. What began for us as a brief affirmative answer—a “yes, of course we’d be happy to do a bit of research”—on that balmy evening in October 2009 turned into a decade of the most rewarding work of our lives.

CC: You begin the book with Marcelo Rivera’s murder. He’s the first of several water defenders to be assassinated in the twenty-first-century fight over mining in northern El Salvador. Why did you choose to begin with his story?

RB and JC: We begin the book with Marcelo’s murder because we wanted the reader to begin where we began: with the horrifying realization that murder can be the cost of protecting the environment in other countries. We knew that people, disproportionately poor and people of color, are killed by the slow violence of chemical poisoning of the air, land, and water by global mining, agribusiness, and fossil fuel firms. Yet, in the United States, seldom do people get murdered for leading these fights for water, for environmental justice.

As the nonprofit, Global Witness, reminds us, hundreds of people around the world are assassinated each year simply because they are environmental defenders. Marcelo was one of these—and his death still haunts us. We dedicated this book to him and three other of the Salvadoran water defenders murdered for choosing water over gold.

We also began the book with the words of Honduran environmental martyr Berta Cáceres, killed five years ago this month: “I knew that we would triumph, the river told me so.”

CC: The book is the sum of over a decade of research and your roles as international allies of the community groups in El Salvador. Did you come across any surprises in your research or during your stays with the Salvadoran villagers?

RB and JC: As readers will discover, there are constant—and unexpected—twists and turns.

But as we contemplated writing a book about this, one of the big revelations for us—something that made writing this book possible—came when we fell into a treasure trove of emails and memos by the mining company executives. Yes, we knew that big corporations usually win because they have more money and they buy political influence. But as we scoured the documents, we were somewhat surprised that the big corporation made a lot of mistakes, often born of hubris and ignorance of the culture into which they were walking. More often than you’d imagine, the top executives underestimated the smarts and sophistication and moral cores of the people who lived in the frontline communities atop the gold. Moreover, the mining executives also inadvertently slighted some wealthier people who should have been their allies.

A final surprise: who knew that this story would lead half-way around the world to the Philippines, a country where we’ve lived and worked over the decades, to find a secret weapon in the final victory in El Salvador?

CC: And lastly, how do you see The Water Defenders connecting with this year’s World Water Day theme, “Valuing Water”?

RB and JC: Most people in richer countries, such as the United States, take clean water as a given. After all, for most of us, it comes with the flick of a wrist to turn on the faucet.

Writing this book reminded us what the people of Texas and Mississippi learned in the recent harsh winter freeze and what many who can’t pay their water bills know well—that most people in the world don’t take access to water as a given. Billions live in communities where water is scarce, and people must fight for the right to clean and affordable water.

In the US, the Poor People’s Campaign of Rev. William Barber is lifting up the voices of people from Flint, Michigan, to Alabama to the Apache sacred lands in Arizona, each of whom are fighting for the right to clean and affordable water. As we explain, their fight is linked to that of communities across El Salvador and the Global South and the lessons to be learned go in both directions.

The slogan of water defenders all over the world says it all: “Water is Life.” Water is indeed more precious than gold.

About the Authors

Robin Broad is an expert in international development and was awarded a prestigious Guggenheim fellowship for her work surrounding mining in El Salvador, as well as two previous MacArthur fellowships. A professor at American University, she served as an international economist in the US Treasury Department, in the US Congress, and at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Broad and her husband, John Cavanagh, have been involved in the Salvadoran gold mining saga since 2009. They helped build the network of international allies that spearheaded the global fight against mining in El Salvador. They have co-authored several previous books together.

John Cavanagh is director of the Washington, DC-based Institute for Policy Studies, an organization that collaborates with the Poor People’s Campaign and other dynamic social movements to turn ideas into action for peace, justice, and the environment. Previously, he worked with the United Nations to research corporate power.