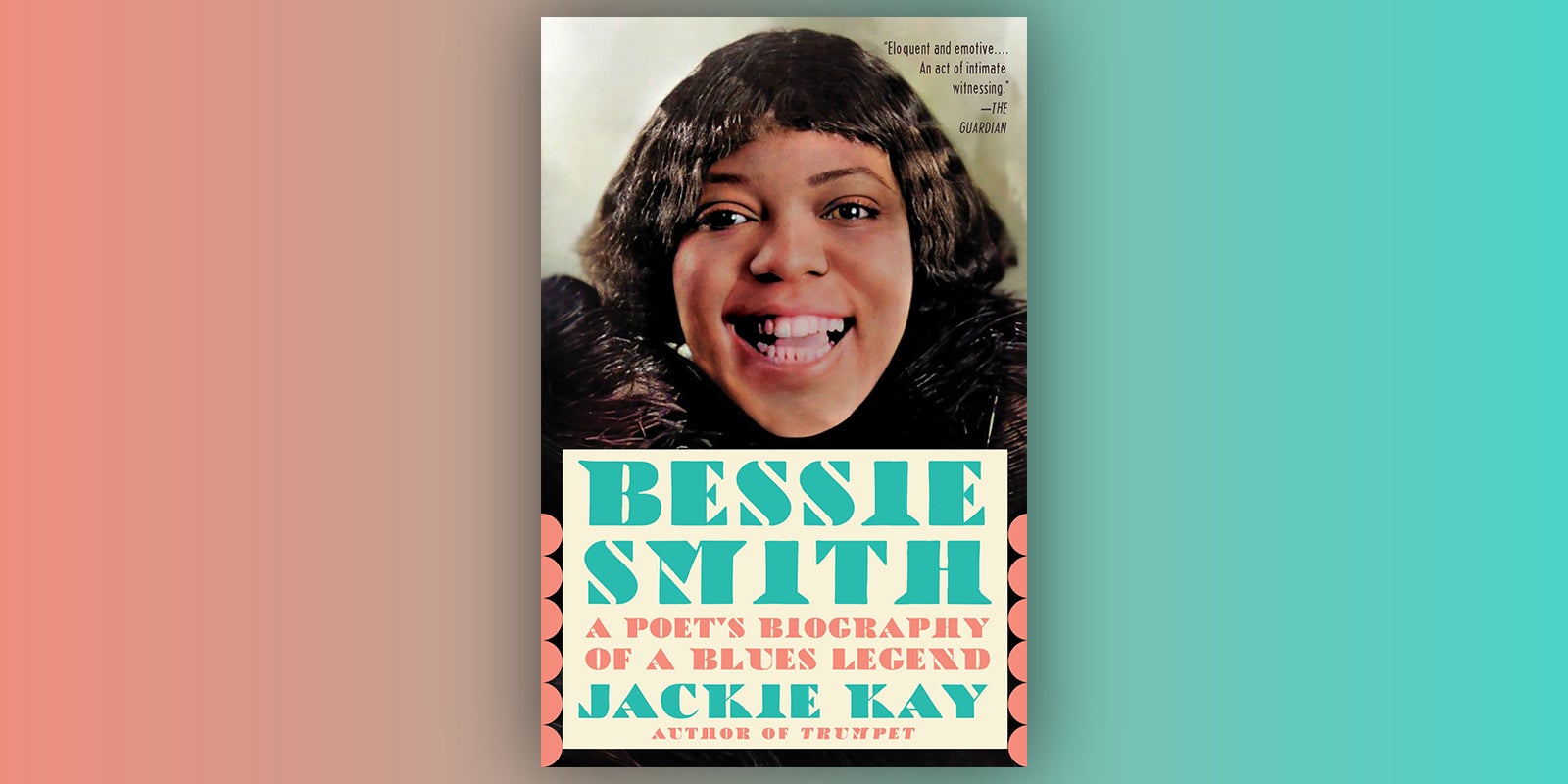

Bessie Smith: A Poet’s Biography of a Blues Legend is at once a vivid biography of a central figure in American music history and a personal story about one woman’s search for recognition. In this remarkable book, Jackie Kay combines history and personal narrative, poetry and prose to create an enthralling account of an extraordinary life, and to capture the soul of Bessie Smith.

Excerpted from Bessie Smith: A Poet’s Biography of a Blues Legend by Jackie Kay

There are some people whose voices ring out across the centuries, who, even after they have gone, possess a strange ability to still be effortlessly here. Bessie’s voice has that quality. Unsettled most of her life, she still unsettles. Try to imagine asking her about anything that is going on today, from the floods, to the climate crisis, to the coronavirus, to the Black Lives Matter movement, to the Me Too movement, to the refugee crisis, and you would find an answer in her rich and resonant blues narratives. We could match any of today’s troubles and anxieties to her music. The blues are not past. Bessie’s blues are current.

Her narratives are even eerily prescient—she sang about floods, about sexual abuse, about financial crashes, about sudden changes in circumstances, changes in love. There isn’t anything that life could currently throw at her that would surprise her. Her blues sought the truth—the truth in all its multiplicity; the hard truth, the strangest truth, the supernatural truth. The whole truth has a different ring to it in the world of Bessie’s blues. In these surreal times, where distinguishing the truth is a challenge, Bessie’s voice has a pure and true ring. She is telling it like it is. There’s nothing fake about her. And because she was not afraid to bear witness to her times, to rising racism and the Ku Klux Klan, to inequalities and class differences, to hypocrisy and the dangers of celebrity, she also manages to bear witness to our times. Pioneers don’t just lead the way in their own time; they continue to refract and reflect our time. Pioneers can perform the magic trick of being contemporary in any time.

For my twelfth birthday, my dad bought me my first double album. It was Bessie Smith’s Any Woman’s Blues. I was drawn to the two-sided picture of her on the cover, the smiling Bessie and the sorrowful one. It wasn’t long before I made her part of my extended imaginary black family, before I felt not just as if she belonged to me, but as if I belonged to her. She felt like kith and kin. She felt like kindred. There was something in her that seemed to recognize something in me. Well, that’s what we think with people whose writing or music or art we love—it is not so much that we see something in their work, but that we are deluded enough to imagine they might understand us, comprehend the complex workings of our minds. They feel like soul mates. We feel known, intimately known.

Now, more than twenty years since I first wrote about Bessie, that feeling is so ingrained in me that it feels a little awkward to state it. It feels like stating the obvious. I’m older now than she ever got to be, twenty years older, and yet trying to imagine her at fifty-seven or at seventy-seven is not all that difficult. Not difficult because the people you choose to accompany you don’t die, they hold up one of life’s oddly glinting mirrors. You’re not the young girl that loved Bessie Smith any more and danced to the blues in your living room. You are a fifty-seven-year-old woman whose odd reflection in the waiting mirror perhaps Bessie would catch? You’re not the same any more. You’ve changed physically, emotionally; you’ve learnt and unlearnt different things. But you still love Bessie. She is one of those folks you go to for comfort and understanding when the going gets rough, the rough gets going.

Bessie Smith is the perfect antidote to these times. She tells no lies. Her voice is still authentic. Her stories seem ever more urgent. She’s still troubled. Her eyebrows still furrowed. Loving her blues, the exact timbre of her voice, no longer even feels like taste or choice. It goes deeper than that. I don’t know what gave me the idea back in 1996 when I first wrote Bessie to write about my life and write about her life together. How odd to try and do both at the same time. I wasn’t interested in writing a standard kind of biography. I think I was interested in how much our interests and passions form part of our own identity—how we beg and borrow and become ourselves, how much of a big mixture we are. I was interested in the point of intersection.

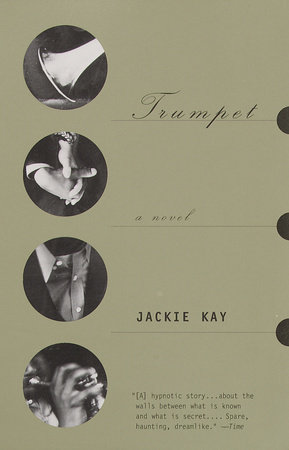

I was working on my novel Trumpet at the time when Nick Drake asked me if I would put on hold what I was writing and choose a gay icon to write about instead. It was strange. I was having trouble with Trumpet in trying to find the right tone to tell the story—and, strangely, returning to the blues and immersing myself in Bessie and in her contemporaries clarified the voice of Trumpet. I started to see the style of the book as a piece of music. The whole called ‘Music’ in Trumpet was directly inspired by thinking about how the blues journeyed into jazz. I was trying to find a metaphor for that fluidity in our own gendered identities. I was thinking about how we imagine states of identity to be static when they are in fact fluid. I had arrived at the conclusion that my hero, Joss Moody, would be called ‘he’ after he made the decision to present himself to the world as a man, and that to refer to him as ‘she’ would be a kind of an affront. Writing about Bessie and her blues, about her very fluid identity, how she was as at home in pearls and plumes as in a man’s suit, allowed me to create Joss Moody. The two books seem twinned. Writing about Bessie unleashed something and Trumpet kind of sprang to life.

Twenty-odd years on it is amazing how much has changed in a relatively short period of time. The shift in attitudes to gay and trans people has probably been the biggest social change of our lifetime. It is not to say that prejudice does not still exist—but still it would have been impossible to imagine all the terms that have so quickly become part of our new vocabulary; we have walked into a changing language about ourselves, which is still shifting, still open to question, still partly greeted with derision in places, but which none the less has reshaped the gendered landscape that we lived in just twenty years ago. I want every bit of it, Bessie sang. I can see my dad, who died last year, sitting in his armchair singing ‘Nobody Knows You When You’re Down Out’.

I can see him relishing the words—the notion that people are fickle and that capitalism is a sham. I can see the enjoyment of the philosophy that is in the blues. There is something egalitarian and equalising about the blues. There are salutary lessons to be found. There’s a terrible reckoning in the space between ‘once I lived’ and now—and there’s nobody to save you. Falling so low is something that might have been predicted. No place to go. It seemed to me, in the way that my dad sang Bessie, that everyone who had ever been poor without ever being rich could yet understand the falling from grace, and could empathize. Everyone might intuit the shallowness of the well-to-do. Might sympathise with the trauma of being left on your tod to cope with whatever after having had ‘friends’. The story of the blues—Bessie’s blues, going from something to nothing, from having happiness to being wretched, from having love to losing it, from being feted to being ignored—those terrible trajectories were all around us. They were real life. The reason that I loved the blues was because they didn’t appear to me to be made up in any way. They sprang from life’s source, life’s true well and, well, they tapped into the well of loneliness on the way, allowed for a kind of transformation, a becoming. If you can recognise the other in you, the other side, then perhaps your life can be meaningful in some way you hadn’t yet imagined.

Blues led the way. It’s hard to think of so much music—jazz, rap, house—without the blues coming first. We can trace the etymology of the blues, the brilliant blues’ bloodline and find it riveting, fascinating, like going onto a genealogy site and finding ancestors. The blues singers are the ancestral voice, the one that can be heard still—those hauntings, those defiant mournful calls. Bessie’s blues are bang up to the minute. She calls and, across the years and miles, we respond.

About the author

JACKIE KAY is the author of the memoir Red Dust Road as well as several critically acclaimed poetry collections—including The Adoption Papers (winner of the Scottish Arts Council Book Award), Off Colour (shortlisted for the T. S. Eliot Prize), and Life Mask (a Poetry Book Society Recommendation)—almost all of which were collected in Darling: New & Selected Poems. Her first novel, Trumpet, won the Guardian Fiction Prize and was shortlisted for International Dublin Literary Award. A former National Poet of Scotland, she has also written several plays and children’s books. She lives in Manchester, England.

JACKIE KAY is the author of the memoir Red Dust Road as well as several critically acclaimed poetry collections—including The Adoption Papers (winner of the Scottish Arts Council Book Award), Off Colour (shortlisted for the T. S. Eliot Prize), and Life Mask (a Poetry Book Society Recommendation)—almost all of which were collected in Darling: New & Selected Poems. Her first novel, Trumpet, won the Guardian Fiction Prize and was shortlisted for International Dublin Literary Award. A former National Poet of Scotland, she has also written several plays and children’s books. She lives in Manchester, England.

© Mary McCartney