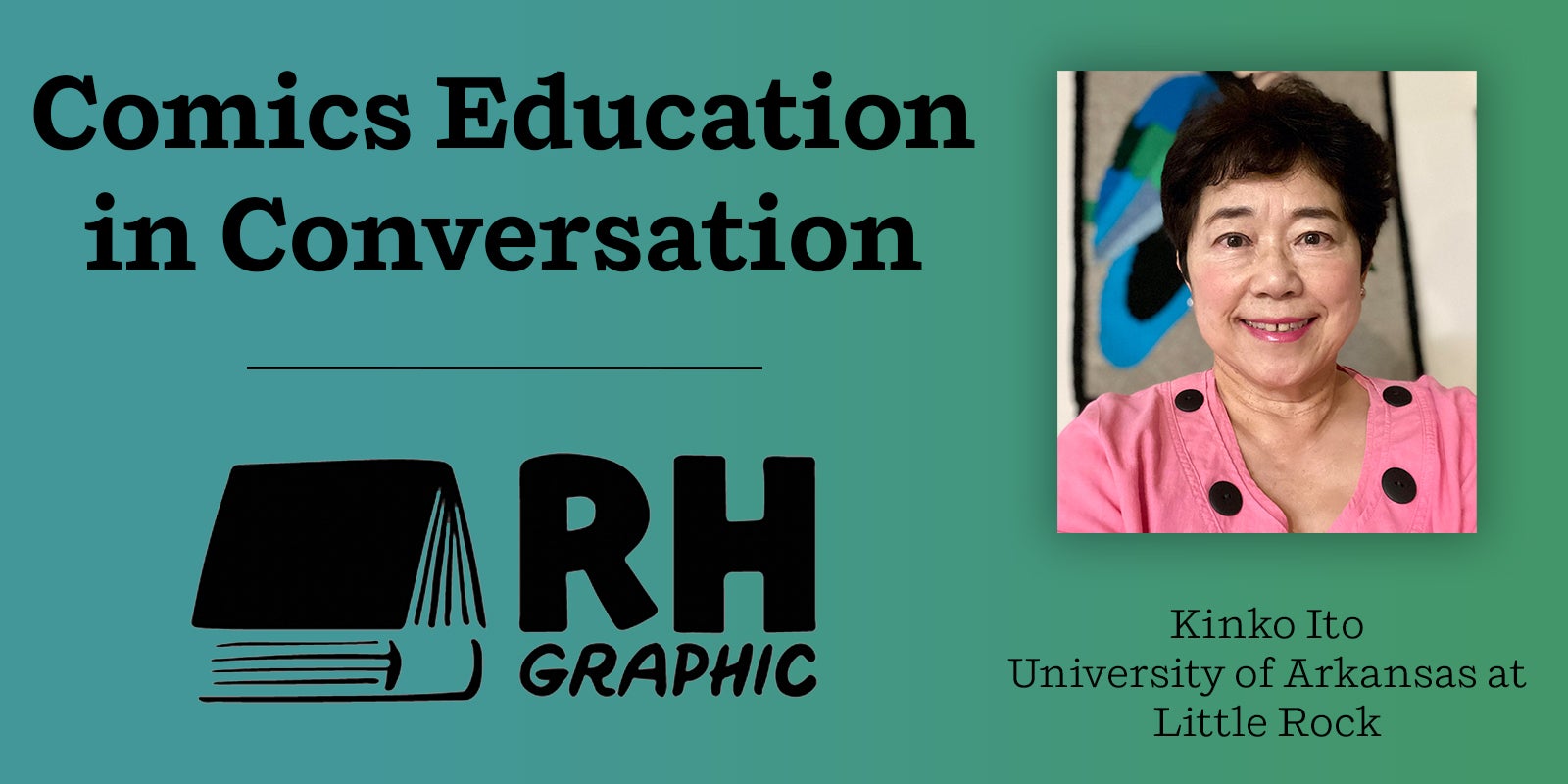

Kinko Ito received her Ph.D. in Sociology from The Ohio State University. She is Professor of Sociology at University of Arkansas at Little Rock where she teaches Introduction to Sociology, Classical Sociological Theory, Organizations, and Japanese Culture and Society. She published numerous articles and book chapters on manga (Japanese comics), anime (animation), and the Ainu (the indigenous people of Japan) in such journals as Japan Studies Review, Journal of Popular Culture, International Journal of Comic Art, and Gurōbaru Kyōiku (Global Education). She published A Sociology of Japanese Ladies’ Comics: Images of Life, Loves, and Sexual Fantasies of Adult Japanese Women (The Edwin Mellen Press) in 2011. Her documentary films “Have You Heard about the Ainu? Elders of Japan’s Indigenous People Speak” (2016) and “Have You Heard about the Ainu? Part 2 Toward a Better Understanding and World Peace” (2018) are available on YouTube. She also published two books in Japan and several Kindle books for general audiences about her world travels, family, grievance, and breast cancer with her pen name K.I. Peeler.

How did you get started reading comics?

I was born and raised in central Japan where manga (Japanese comics) are the major and legitimate form of popular culture and entertainment along with film, theater, music, and sports. Manga as visual texts have a very long history, and they are actually a national obsession. I started reading comics when I was in the first grade.

My mother taught me how to read and write Japanese when I was about four years old using square wooden blocks that had letters on one side and pictures on the other. The Japanese language uses more than a few thousand Chinese characters in addition to hiragana and katakana (Japanese characters). Thanks to Ruby, hiragana written in small fonts next to difficult Chinese characters, children can read manga easily. Throughout my elementary school years, I had a subscription to an educational monthly magazine recommended by the teachers. It was specifically published for a specific grade and contained photographs, reading materials, and a few comic stories.

My mother was a principal at a municipal kindergarten then, and she was one of those people who believed that reading comics only was detrimental to my academic development. She prohibited me from purchasing them. I borrowed them from my friends in the neighborhood. My cousin subscribed to a weekly comic magazine for boys and youth, and he often purchased other brands’ magazines as well. I had a free access to his vast collection of comic magazines, each of which contained about a dozen serialized comic stories with themes like adventure, history, violence, sports, humor, and gag.

Various genres of Japanese comics are roughly divided by the sex and the age (children, youth, young adult men and women, mature women, etc.) as well as among different topics, special interests, hobbies, fetishes, and drawing styles. In my childhood, I was exposed to both girls’ and boys’ comics. Possibly, it is one of the reasons why I grew up to be androgynous. I loved reading about both girls’ and boys’ hopes, dreams, fears, adventures, psychology, and humor.

How did you get from your first comics-reading experience to doing academic work in the medium?

Manga have a very long history in Japan, and they include visual texts such as picture scrolls, graphic stories, and modern comic books and weekly and monthly comic magazines. Cartoons, pictures, and illustrations are also used as a legitimate means of disseminating information and as an effective pedagogical method. Visual images are utilized in manuals, signs, newspapers, magazines, and advertisements more often than in other nations. Comic books and magazines are sold in various stores, and they are available in both public and school libraries as well as at ramen noodle restaurants, cafés, and doctors’ waiting rooms. Basically, the Japanese in general are surrounded by the visual texts in their everyday life. Manga are truly popular entertainment of the masses in Japan and are not considered as low brow. They, however, became an interdisciplinary academic discipline only recently.

I read manga up to my freshman year at college when I switched to reading literature. I seldom read manga while I was an undergraduate student, but when I visited my friends’ homes, I borrowed their manga. When I was a graduate student at The Ohio State University, senior Japanese students in graduate and professional schools, who were mostly men, occasionally let me borrow their comic books which they brought from Japan or which were handed down to them. The comics were the must-read classics. I enjoyed reading them.

My first academic interest in comics took place when I was an assistant professor of Sociology and convener for the Gender Studies Program at University of Arkansas at Little Rock. I used to fly to Japan to visit my parents and friends a few times a year. I took a Shinkansen Express to Nagoya after visiting my friends in Tokyo one time. I think it was in December, 1989 or 1990. A few weekly comic magazines for men were left in the pockets on the back of the seats in front of me, and they got my attention. I was so absorbed in reading them that I arrived at Nagoya in no time.

The magazines I read belonged to a category of comics for young adult men, and I had not been familiar with this genre. I enjoyed reading them but was also surprised at the sexist nature of the certain comic stories. Female characters were generally depicted as a very minor role for the development of the stories. Many of them were in traditional pink-collar occupations and fit the gender stereotype of an ideal Japanese woman. On the other hand, totally different female characters were also portrayed – gorgeous, strong, shrewd, oversexed, and even violent. In some comic stories sexual harassment, kidnapping, rape, incest, lynching, and murder appeared as common scenarios. I must mention here that the “fantasies” in the comics rarely translate into reality. Some women were portrayed as feminine, adorable, and warm-hearted, especially when they were male protagonists’ loved one such as their mothers, sisters, grandmothers, and girlfriends. Other female protagonists were depicted as intelligent, powerful, masculine, responsible, and independent. They had a combination of both feminine and more androgynous psychological traits. I enjoyed reading the magazines, but I was perturbed by some elements of deep-seated sexism, patriarchal standards, and prejudice as well as derogatory depictions of women. I wrote several articles on various aspects of Japanese comics for men at the beginning, and then I expanded my research to adult women’s comics. I also analyzed the comics’ general functions in society: an agent of socialization, a trend setter, a bonding agent, formation of political ideologies, and providing psychological satisfaction and catharsis.

Have you seen a change in the academic and/or popular reception of comics and graphic novels over the course of your career?

My answer is yes and no. There is more academic and social acceptance of the field of manga studies in recent years. For example, there are Japanese universities and colleges that have an undergraduate degree program in the Comics Studies. Specialized professional schools started offering courses on how to create and draw manga in the last 15 years or so. Academic associations were established in Japan and elsewhere and began publishing their research.

Certain genres of manga for adults that include the depiction of pornography, nakedness, violence, and sex are de jure off limits to those who are under 18 years old in certain municipalities. However, they are available to anyone including students because the adult family members, friends, or neighbors can purchase them, and the children might have an easy access with or without the adults’ knowledge. Those who are quite critical of manga think the overt sexual fantasies, expressions, and violence are detrimental to youth and children. They have appealed to the city, state, or national governments to ask the industry to control the contents and the sales.

Mr. Kazuji Kurihara, an ex-editor-in chief of Futabasha, one of the larger publishing houses in Tokyo, said that the traditional sex and age lines that divided different genres of manga have been merging lately. Many elementary, high school, and university students as well as adults of both sexes now read comics for boys and men. There are also young men and adult men who like to read Ladies’ Comics. Over all, manga have a legitimacy in Japan, and talented manga artists are recognized and awarded prestigious prizes by the Japanese government, newspaper companies, publishers, museums, and various communities each year.

Manga in general started to attract much academic interest and gained acceptance as a legitimate field of study in the 1990s when I started studying them. Manga were a totally new subject matter for me. A sociologist studies and analyzes the comics by using content analysis, and manga contain a gold mine of research topics for any sociological field such as family, socialization, sex and gender, economy, organizations, politics, religion, communication, roles, stratification, and environment.

I first met Dr. John Lent at one of the academic meetings in the early 1990s, which changed the course of my life as an academic. John is always generous, kind, supportive, and inspirational. He became my mentor and friend. John started a bi-annual academic journal called International Journal of Comic Art in 1999, and he became the editor-in-chief. Japan Society for Studies in Cartoon and Comics was established in 2001, and it publishes its academic journal Manga Studies.

You’re a sociologist! How do comics and sociology fit together?

I was in a Master’s program in Linguistics at OSU for a while, but I started to lose interests. Going back home without a degree was not my option. The department chair told me that I should check the Sociology program since I liked sociolinguistics.

One day, I saw Mr. Yamamoto, a Japanese Ph.D. student in Sociology, in a cafeteria. He said, “Sociology studies whatever is taking place in our society — people, social interactions, organizations, events, or institutions. Even a striptease theater can be a subject matter of Sociology.” The words “a striptease theater” got my attention. Mr. Yamamoto told me how sociologists would employ the methodology of participant observation, study, and analyze social interactions between the dancers and audience. He later gave me a few textbooks. I fell in love with Sociology.

Manga are visual texts, and the readers can enjoy visual arts (facial expressions, sceneries, objects, etc.) and texts (words, sentences, etc.) at the same time. I used a sociological methodology of content analysis in order to study and analyze encounters, events, and experiences of the protagonists of manga, and it was analogous to participant observation.

You specifically write about girls and women in manga. Can you talk about what drew you to those works?

I borrowed my friends’ girls manga collection when I was young, but I have no detailed recollection of how and where I started studying adult women’s comics. (The word “adult” here does not mean pornographic.) Ladies’ Comics (LC) started as a new genre of manga when the women who grew up reading girls’ manga became older and wanted comics appropriate for their age. They wanted something that entailed more than a school romance between a teenage girl and a boy. LC were established in the early 1980s when manga in general truly gained popularity and legitimacy as entertainment. One of the women editors-in-chief I interviewed in Tokyo said, “It was the time when publication of manga meant an instant huge profit.” The boom coincided with the high-flying “bubble economy” that boosted the people’s spending and allowed more than 85% of the Japanese to classify themselves as middle class. Many new LC magazines were established by publishers big and small at the time, and many girls’ manga artists started to draw for LC with different contents and themes.

For my book A Sociology of Japanese Ladies’ Comics Images of the Life, Loves, and Sexual Fantasies of Adult Japanese Women (Edwin Mellen Press 2011), I read more than 10,000 pages of LC in order to analyze the content. LC have different genres of stories, and just about anything is possible in the stories! The categories include romance, love, family, compassion, suspense, home economics, medicine, professions, social problems, horror, and various types of sexual encounters and fantasies.

You’ve done academic work on manga! How does manga fit into the academic conversation about comics? Is it treated the same way as European or American comics?

I don’t know much about European or American comics, and thus I cannot really answer this question. I can say that in Japan, manga are more than just “comics” regarding their social functions and popularity. The Japanese love visual texts, and they are definitely a part of prestigious national tradition as art, literature, and entertainment. Manga studies have been recognized as a legitimate discipline, and various organizations including the Japanese government award manga artists prestigious awards year after year.

Teaching manga in the US would seem to mean that there’s always some level of translation in the conversation – both with language and with cultural elements in the text. How do you tackle that in your work and with students?

I teach Japanese Culture and Society course, and manga and anime are used to learn some elements of Japanese culture and society. I always have avid fans of manga and anime in the class, and they are very happy at the end of the semester. They all agree that their favorite manga and anime now make a lot more sense thanks to the class.

You’ve also done documentary film work! Do you find that there’s a crossover in the visual elements in both those spaces?

Traditionally, sociologists, just like any other academicians, published their research in academic journals, monographs, and magazines for general readers. Sociologists have depended on verbal and written data for their research. Only in the last few decades have sociologists started to utilize visual information such as advertisements, photographs, documentary images, and videos for their analysis. They give us new ways of conceptualizing aspects of our society. With this new dimension of Sociology in mind, I have used multimedia to present my ethnographic data and to analyze how elderly Ainu live in contemporary Japan. The audience can learn about the indigenous group not only from my presentation of the basic information but also they can see and hear the elders talk about their own experiences. Japan has what an American anthropologist Edward Hall termed a high context culture in which non-verbal cues play a very important role in communication. Smile, silence, grunts, eye movement, gestures, tone of voice, and other non-verbal communication is only possible in the multimedia presentation. The audience can easily see human emotions such as joy, happiness, sadness, anger, or resentment. This is the same in manga. There may not be any bubbles with words and sentences in a particular scene, but the visual images of the facial expression and body postures of the characters often speak about their emotions and much more.

There’s long been a call for increased diversity in comics – and that’s only gotten more prominent. What are you seeing changing in this space today?

Japanese manga indeed cover various aspects of the social reality – the people, their lives, adventures, dreams, fantasies, occupations, etc. Certain manga protagonists and their stories have been quite influential in Japanese society over the years. Manga are also educational as they teach values, history, philosophy, morals, and knowledge and information. Inclusion and equality are part of the most important recent social issues in today’s Japan. Japan is a modern nation, but much prejudice and discrimination still take place in everyday life of the people. One of the most recent phenomena is the recognition and more acceptance of LGBTQ+ people and their movement. Social and psychological issues surrounding these people often appear in newspaper and magazine articles, on TV, and other places.

Favorite or new graphic novel recommendations?

My Brother’s Husband by Gengoroh Tagame is a Japanese comics that has gotten much attention worldwide recently. The manga was originally serialized in Gekkan Manga Akushon (Monthly Manga Action) which is published by Futabasha in Tokyo. Interestingly enough, the manga in the United States are published by the Pantheon Books, which is a subsidiary of Random House.

My Brother’s Husband is a heart-warming and a bit sentimental story about a family in Japan. It has humor that everyone can enjoy and appreciate, too. The protagonist is Yaichi Origuchi, a divorced, stay-home single father, who has a young daughter in the 3rd grade. The story starts with a visit by a Canadian named Mike who married Ryoji, the twin brother of Yaichi. Ryoji passed away and Mike decides to go to Japan in search of his memories with Ryoji and his past before he left for Canada. The manga artist depicts general prejudice and discrimination (both overt and subtle) against the LGBTQ+ people in Japan as well as the protagonist’s own negative perception of the people. The themes include people’s reaction to gay marriage, a youth who had a problem coming out, and the meaning and significance of “marriage” and family. Gengoroh Tagame was given several awards for this manga, and as a sociologist I highly recommend this manga to all people.

SOCIAL MEDIA

Twitter: @KIPeeler