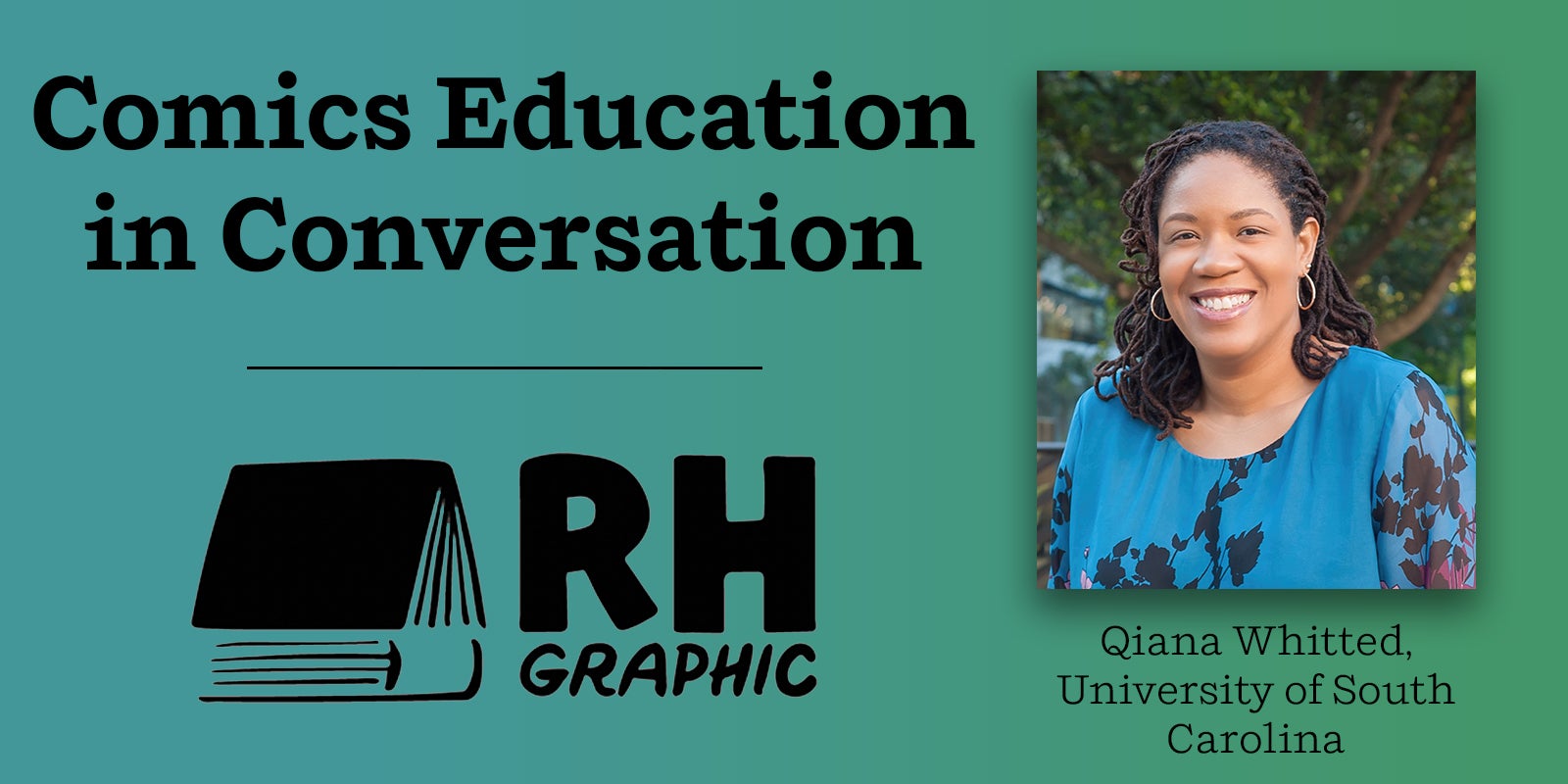

This week we kick off a new series ‘Comics Education in Conversation,’ in which Gina Gagliano, the Publishing Director of Random House Graphic, Random House Children’s Books’ dedicated kids and YA graphic novel publisher, shines a spotlight on comics in academia and education. Each month, this series will feature an interview with a different academic or educator, speaking about their work in the field. Comics belong in the classroom – in every classroom from kindergarten to college – and this series explores the work being done to get them there, alongside how they’re used once they’re there.

Qiana Whitted is a Professor of English and African American Studies at the University of South Carolina, as well as the Director of the USC African American Studies Program. She is the Editor of Inks: The Journal of the Comics Studies Society and Chair of the International Comic Arts Forum. A graduate of Hampton University with a PhD from Yale, her research focuses on African American literary and cultural studies as well as American comic books. She is author of the monograph, “A God of Justice?”: The Problem of Evil in Twentieth-Century Black Literature and co-editor of the collection, Comics and the U.S. South.

How did you get started reading comics?

My earliest encounters with comics as a kid were mostly Garfield and other funny newspaper strips, Archie, and MAD magazine. Anything that was as silly or as gross as Garbage Pail Kids trading cards pretty much got my attention. It wasn’t until I was a freshman in college at Hampton University that I was brave enough to venture into Bender’s Books and Cards, the local store near campus that sold comics. I was into horror and fantasy by then, so it didn’t take me long to find my way to Spawn and Vertigo titles like Sandman and Hellblazer.

Then – how did you get from your first comics-reading experience to doing academic work about the medium?

After I started working at the University of South Carolina, I was offered the chance to teach an accelerated summer class on a special topic. I proposed a course on “Neil Gaiman’s Sandman and the Hero’s Journey” in 2005, and although it didn’t fall within my main area of specialization in African American literature, my department’s undergraduate director was curious and encouraging. In the process of exploring materials to help with my instruction, I realized that there was an entire field of study devoted to comics scholarship. I began to read the work of Will Eisner, Scott McCloud, and Thierry Groensteen, and over time my academic research on African American culture and southern studies began to intersect with the kinds of comics that I was reading and teaching. A year after I published my first academic book on literary criticism, I traveled to Chicago for my first comics studies conference to present a paper on slavery and Swamp Thing. Even more exciting was getting to know and eventually collaborate with other scholars like Brannon Costello, Rebecca Wanzo, Brian Cremins, and John Jennings who share the same crazy mix of personal and professional interests in comics and issues such as race, history, genre, and southern studies.

Have you seen a change in the academic (and/or popular) reception of comics and graphic novels over the course of your career?

Yes, although the roots of comics studies go back quite a few decades, I’ve seen the field grow much wider over the last ten years in terms of the kinds of interdisciplinary approaches and methods used. More women and scholars of color are also making their academic home in comics studies and many of them are doing so earlier in their careers. It is exciting to see graduate students in English, history, media studies, art, and library science making comics the center of their research – instead of coming to the field later, as I did. And I’m looking forward to a time when every campus will treat comics studies scholars as a necessary part of their faculty. At the same time, like most popular culture studies, misconceptions about the value of comics scholarship still persist: that comics are just for kids (or only for adults), that superheroes are the only comics genre that matters (or that only graphic memoirs can be taken seriously), that critical scrutiny somehow drains comics of their joy. It’s much easier to dispel these myths than it used to be!

You’re the president of the International Comics Art Forum. What does ICAF do, and should academics and educators interested in comics get involved?

ICAF is a symposium that brings together comics studies scholars and creators from around the world each year. When it started 25 years ago, the gathering was one of a kind, with only a few presentations and roundtables. Today the event attracts several dozen scholars over three days and the executive committee works hard to maintain its character as a close and affirming space for academics of every rank to discuss their research, learn directly from comics writers and artists about their process, and build community. Our activities will be virtual this year due to concerns about COVID-19, but our next conference is scheduled to take place at the Savannah College of Art & Design in early 2022. Academics can stay in touch with us through our website, where we have a mailing list and links to our social media: http://www.internationalcomicartsforum.org/

Your latest book was EC Comics: Race, Shock, and Social Protest. What drew you to these comics, and to this topic?

My love of Golden Age horror comics like Tales from the Crypt first drew me to EC (which stands for “Entertaining Comics”) and of course, I’ve been a fan of MAD since I was a kid. But it wasn’t until much later that I learned that this post-World War II comic book company was also known for producing shock comics that directly engaged social and political messages for readers in the U.S. These comics were called the “preachies” – short morality tales that used some of the same tropes and visual techniques from EC’s infamous horror, crime, and science fiction comics to address racism, anti-Semitism, Cold War-era red-baiting, and other forms of social discrimination. My book takes a closer look at the strategies behind these stories and considers their impact on readers during the period. The preachies are an important part of understanding the development of the comic book industry, particularly considering how some of the more controversial titles made their way into the debates over juvenile delinquency in the 1950s.

Tying into that, there’s been an ongoing discussion about the importance of diverse representation in comics, and diverse authors creating comics. Is that something you see in your work as well?

Despite a long and troubling history of racist caricature in comics, there have always been voices demanding something different. That is what I hope my work helps to make clear. As early as 1901, editorial writers for The Colored American newspaper were calling for Black cartoonists. Teenagers were petitioning comics publishers in the 1940s to set aside racial stereotypes, while Black writers and artists were working hard to create their own comic books. I think that taking this long view helps us to ask questions not only about what we see on the page, but about access to resources and about the people in positions of authority who make decisions. Obviously there are still a lot more stories to be told. But readers interested in diverse representation have always been a part of comics and it is thrilling to see these interests now reflected in crowdfunding and small press titles on up to acquisition editors and new imprints at large publishing companies.

What are you working on now?

This is my second year as editor of Inks: The Journal of the Comics Studies Society, a journal that publishes scholarly research on all forms of sequential art, graphic narrative, and cartooning. I really enjoy reading the submissions and getting a sense of new work in the field, even if it is produced by academics who don’t necessarily call themselves comics scholars. I’m also editing a collection of essays on blackness in early American comics. While my book on EC focuses on a single publisher’s efforts, this new collection will take a broader look at what representations of race can help us to understand about the growth and development of the comics industry from the turn of the century through the 1950s. I also recently published two short essays: a post about the Brazilian graphic novel, Angola Janga: Kingdom of Runaway Slaves by Marcelo D’Salete, and a review essay on the Eisner Award-winning comics collection, Hot Comb by Ebony Flowers.

Favorite or new [book] recommendations?

Three of my most recent favorites are: The Content of Our Caricature: African American Comic Art and Political Belonging by Rebecca Wanzo, Graphic Memories of the Civil Rights Movement by Jorge Santos, and Incorrigibles and Innocents: Constructing Childhood and Citizenship in Progressive Era Comics by Lara Saguisag.