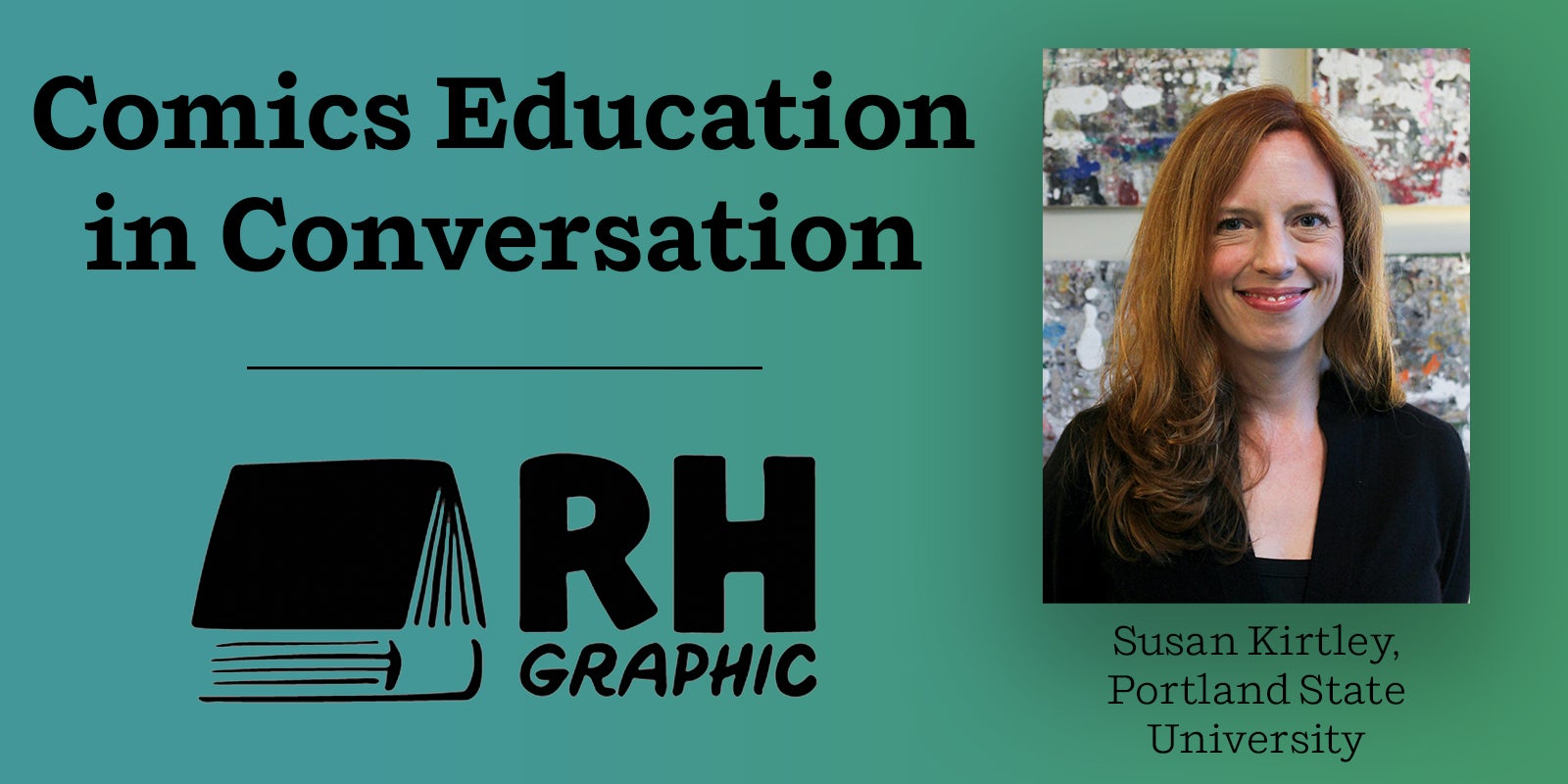

Susan Kirtley is a Professor of English, the Director of Rhetoric and Composition, and the Director of Comics Studies at Portland State University. Her research interests include visual rhetoric and graphic narratives, and she has published pieces on comics for the popular press and academic journals. Her book, Lynda Barry: Girlhood through the Looking Glass, was the 2013 Eisner winner for Best Educational/Academic work and she served as a judge for the 2015 Eisner Awards.

How did you get started reading comics?

I started reading comics because I was told that “girls don’t read comics” by a classmate in elementary school. I have a contrary personality, so if I’m told I can’t do something, I will pursue it with a passion. And that’s exactly what I did; I accompanied my mother to the grocery store and pulled a comic book off the spinner rack and I was hooked. I started reading superhero comics, which I loved because they were basically soap operas with lots of punching. Furthermore, at the time they were the only comics I could find. There are so many more options for kids now! I’d be jealous except I still read all kinds of comics—for adults and children. They are so good, why would I limit myself?

Then – how did you get from your first comics-reading experience to doing academic work about the medium?

I’ve been reading comics since childhood, but it wasn’t until much later that my interest in comics entered into my academic life. I studied language and literature and eventually received a Ph.D. in Rhetoric and Composition, all while continuing to read comics. I was teaching an undergraduate memoir class and decided to read Lynda Barry’s One Hundred Demons with the class. The response from the students was tremendous and inspired really important conversations about gender, race, and class, and from that point on, I started to realize the power of comic art in education. I wanted to learn more and set out to study comics from an academic perspective, bringing my training, education, and passion for comics together. These days I feel incredibly lucky that I get to teach, read, and study comics as part of my job!

Have you seen a change in the academic (and/or popular) reception of comics and graphic novels over the course of your career?

Over the past twenty years or so, the academy has truly started to embrace comics, as evidenced by the flourishing field of comics studies. There are numerous academic conferences, journals, and scholarly societies devoted to comics, not to mention scholarly books devoted to the field. It is exciting to be a part of this truly interdisciplinary field from the beginning. And when I visit K-12 schools and libraries I’m delighted to find librarians and educators promoting and reading comics with students. Unfortunately, I’ll still occasionally come across critics and doubters, most of whom have never even picked up a comic! I want to tell them to read just one of the great comics available now. There really is a comic for everyone!

Aside from comics, you also teach rhetoric and composition. Is there an overlap between those three areas?

I’ve found my training in rhetoric and composition to be very helpful in teaching and thinking about graphic narratives. As a compositionist, I’m interested in the creator’s process in crafting comics, and I encourage my students to create their own graphic narratives as a way of communicating differently and of thinking through ideas. Some students are visual learners, and this technique can be especially liberating. My rhetorical training encourages me to think about the ways in which comics make an argument to an audience. Does the comic use the repetition of images to emphasize an idea? Is the comic using pathos and playing on our emotions? Comic art is actually incredibly complex, and rhetoric gives me tools for analysis.

You’ve done some of your academic work on Lynda Barry. What inspired you to write about her?

My adventure teaching comics started with Lynda Barry, and as a compulsive researcher and someone who tends to prepare obsessively for class, I like to read everything written by and about every author I teach. Lynda Barry is a huge figure in the world of comics, and, for that matter, is also an amazing novelist, painter, essayist, teacher, and playwright, and I was shocked when I discovered that there was very little scholarly attention to her work. My book about Barry was an effort to begin to fill this gap, providing a resource and encouraging others to write about this important creator. I find it exciting and sometimes intimidating that, as a new field there is so much work yet to be done in comics studies.

We’ve been seeing an increase in women in comics over the past decades. How has that been reflected in the books you’re seeing, an in academia?

I started reading comics because I was told that “No girls were allowed,” and for many years I found myself the only female in the comics shop. I think that has been changing, both in scholarly circles and in the larger comics community. There are more and more diverse scholars and it is really changing the conversation in significant ways. I think this trend will only continue.

Your latest book was on comics pedagogy. What’s happening in that space, and has how it changed over the years?

People are coming to understand that comics and graphic novels do not necessarily mean superheroes. That’s nothing against superheroes, but comics are a medium and not a genre, and you can tell any kind of story in a comic. To that end, comics are becoming more mainstream in schools from kindergarten through graduate programs, and comics pedagogy is an area that is really flourishing. I’ve noticed that comics are being taught as a way of introducing content in classes across disciplines. For example, you might find Maus by Art Spiegelman or March by John Lewis, Andrew Aydin, and Nate Powell in a history class. And some classes focus exclusively on comics as the subject, with courses on Comics History and Autobiographical Comics taught at various universities. I’m also excited about classes in all areas that are incorporating comics as a way of communicating and of thinking through ideas. I will sometimes ask students to do a short comic summary of a novel, an activity that encourages students to really focus and figure out the most important ideas in a text-based book. I was also thrilled to see a middle-school science teacher inviting students to draw a comic about scientific concepts. Comics have a long history as educational tools, and I believe this area will only grow in the future.

What are you working on now?

I’m completing a new book called Typical Girls: The Rhetoric of Womanhood in Comic Strips from Ohio State University Press, which explores a sampling of female-created comic strips from 1976 to the present through a rhetorical framework, filling a gap in current scholarship and giving these works extended scholarly examination, focusing on defining and exploring the ramifications of this multifarious expression of women’s roles at a time of great change in history and in comic art. While that sounds really fancy, this was really an opportunity for me to read some great comic strips like For Better or For Worse, Sylvia, Cathy, and Where I’m Coming From, just to name a few. It’s been a fascinating project to look back at these comic strips from forty years ago and see how incredibly relevant they remain.

Favorite or new graphic novel recommendations?

This is an incredibly hard question, since I read everything I can, and my favorite is generally my current read. I love superheroes and non-fiction and mysteries and books aimed for children and adults. I thoroughly enjoyed Cardboard Kingdom and the 5 Worlds series. I’m a big fan of Ms. Marvel and Thor. And I recently re-read March in honor of John Lewis and it’s gotten me thinking about the notion of “good trouble” in the best possible way