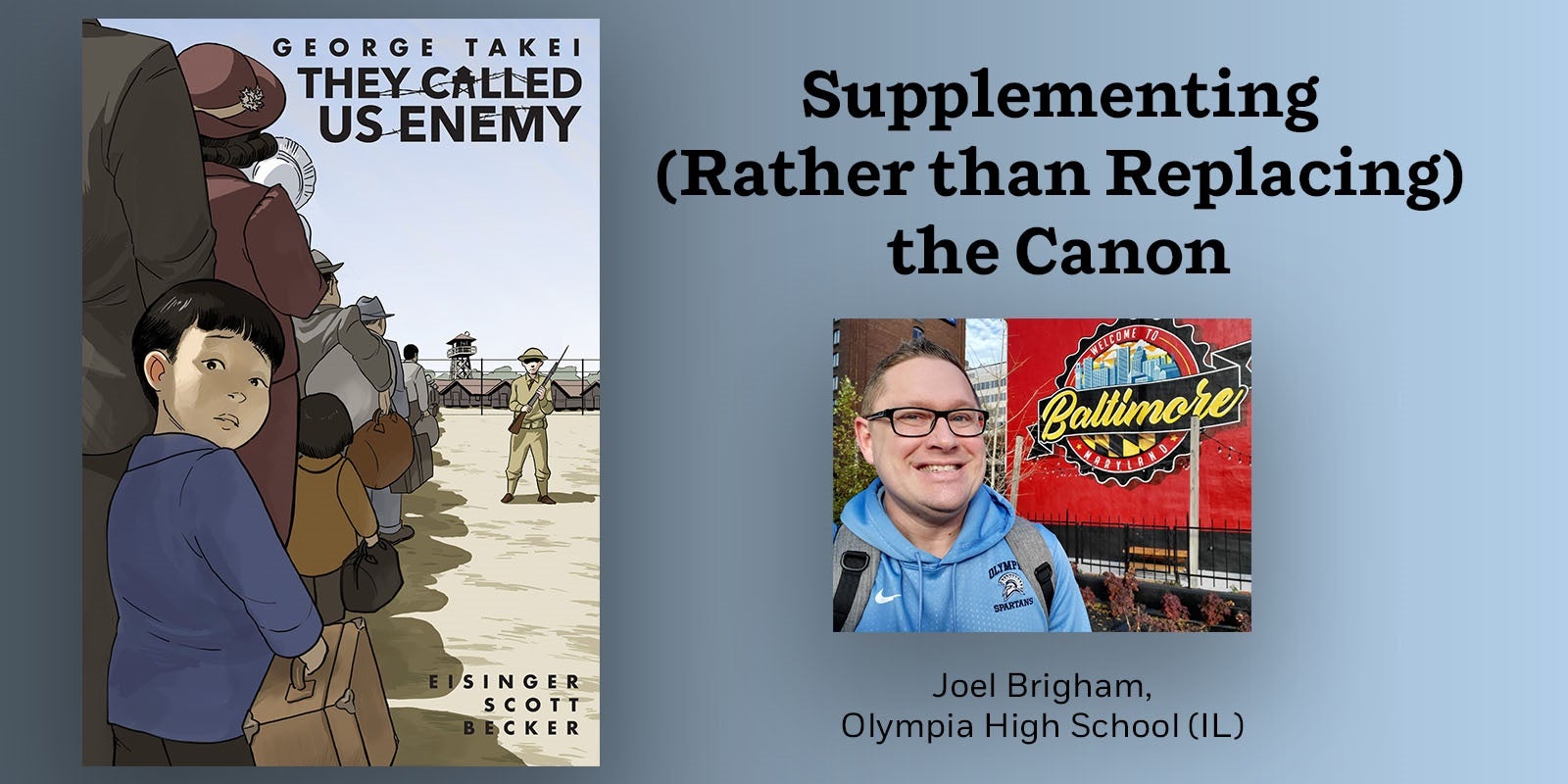

By Joel Brigham

I have taught American Literature for 16 years, and for most of my career, that has meant doing what has always been done. I’ve taught Ralph Waldo Emerson and Mark Twain and F. Scott Fitzgerald and Ernest Hemingway, just like any other self-respecting American Lit teacher in this country, but it was until recently that I realized a couple of very important things:

- The concept of “The Canon” is arbitrary, and,

- American Literature is a whole lot more than a bunch of old, dead, white dudes.

I’m lucky to work for a principal who believes in adding more diverse texts to classrooms, even though I teach in a mostly-white, rural district in Central Illinois, so when offered the opportunity to add a couple of new books to my American Lit curriculum, I pounced on it with the joy of a child being offered a bag of lollipops. New books? Absolutely. Yes, please.

Supplementing (Rather than Replacing) the Canon

One of the texts I purchased with this found money was George Takei’s, The Called Us Enemy, an autobiographical graphic novel about Takei’s childhood experience as a Japanese-American forced to live in an internment camp following the bombing of Pearl Harbor.

The book is great. But when I added it to my curriculum, I didn’t do so without a plan. Rather than boot canon entirely, I pitched this addition as a way to supplement canon with more recent books written by more diverse authors.

In this case, my plan was to pair TCUE with Arthur Miller’s The Crucible, an allegorical play from the 1950s set in Salem, Massachusetts during their infamous witch trials. Getting kids to read The Crucible has never been a tough sell. They can’t get enough of the Salem Witch Trials. I also didn’t think it would be especially tough to get them to invest in a graphic novel. Even big kids like stories with pictures.

The link between these two works is the concept of using fear to drive persecution. Again, I teach in a rural, mostly-white district, and what I ultimately wanted to do was build empathy in them for the people affected by President Trump’s Muslim ban, as well his border policies that have left many children separated from their parents. I knew that together, these books could help me achieve that.

So we read The Crucible the same way we always had, giving the students plenty of time to gripe about how nasty Abigail is and how unfairly the Puritan court system treats the accused. They get angry. They get invested.

Then I move them into the history of McCarthyism in the 1950s. Miller, the playwright of The Crucible, intended his story about a hapless witch hunt to serve as an allegory for what was happening in the United States during that decade. Again, it is not hard to inspire indignance in students as they wrap their heads around the unfair treatment of suspected Communists by Joseph McCarthy and his House Un-American Activities Committee.

After all that, we come TCUE. When I attended the National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE) conference in the fall of 2019, I was given the opportunity to meet George Takei and chat briefly with him about my plans to pair his graphic novel with Arthur Miller’s play. A huge smile spread across his face when I mentioned my idea. “That’s perfect,” he said. “Absolutely perfect.”

And he would know, since he went through a crucible of his own in the 1940s.

In the wake of WWII and the Pearl Harbor bombing specifically, many Americans were so afraid of anyone who looked even remotely Japanese, the sat back as the government rounded up everyone with any association to their enemy and locked them in literal internment camps. It didn’t matter if Takei and his brother were born in America. It didn’t matter that his immigrant parents were legal American citizens. Off they all went, along with thousands of other Japanese-Americans to camps. These people lost everything they owned, from homes to businesses, all so the majority of Americans didn’t have to feel scared.

It’s the same reason the courts in Salem put scores of people in jail and executed 19 innocent people. It’s the same reason McCarthy made sure innocent people lost their jobs and were ostracized by their communities.

It’s also the same reason Trump campaigned on a border wall meant to keep immigrants away, and it’s the same reason he instituted a travel ban on Muslims almost immediately after he took office.

And that’s the endgame of a unit pairing The Crucible with They Called Us Enemy: getting students from Salem to World War II to McCarthyism to Trump. I couldn’t start this unit with the Muslim ban and the kids in cages, but I did end there, and what I’ve found is that teens’ empathy for these people increases as they get a sense of what it means to be on the wrong end of that kind of discrimination. Reading books like Takei’s They Called Us Enemy is a great way to get that point across, and it’s why I teach it in my American Lit class alongside canon.

Frankly, I can’t wait to integrate more diverse texts into this curriculum, not as a means of eliminating valued canonical curriculum, but by supplementing it.

More Practical Takeaways

At the beginning of this unit, I suggest telling students what the summative assignment is going to be, which in this case could be a comparative thematic analysis of The Crucible and They Called Us Enemy. What I did with my 11th graders was provide the prompt and the themes I wanted them to find while reading. While you can do anything you want with these texts from day-to-day, it’s nice to have a big, overarching goal for reading, as it prevents students from merely glossing over pages.

In this case, I give them the following list of themes (though for a larger challenge, you certainly could have the students locate the themes themselves), and I ask them to take notes any time they find a quote or a plot point that seems as though it shows those themes in action.

Here’s a list of themes that show up in both texts:

- The negative impacts of hysteria

- The loss of one’s reputation

- Overcoming judgment

- The loss of (or fight over) property

- Social status’s role in being cast as “other”

- Ultimately finding justice

- Offering forgiveness (even when it isn’t necessarily deserved)

- Those in power embracing what is morally wrong

- The strength of women during hardship

- How humans deal with guilt

For the summative assessment, I have the students write comparative analyses of any three of those themes they’d like.

Specifically, I have them:

- Use textual evidence to show how the selected theme manifests itself in The Crucible.

- Use textual evidence to show how the selected theme manifests itself in They Called Us Enemy.

- Explain the similarities and/or differences between how these themes are treated in the two texts.

In terms of skills, I assess them for the following:

Reading Comprehension

- Student can identify a theme from a novel, play, or work of narrative nonfiction.

- Student can include textual evidence of that theme.

- Student can explain the relevance of the found textual evidence.

Informative Writing

- Student can draw evidence from literary texts to support an analysis.

- Student can compare two texts that treat similar themes or topics.

To conclude, these texts provide great fodder for daily conversations and debates throughout the unit, including with current events, but there’s also plenty of academic value in using the texts for deeper, text-focused analysis.

The bottom line: canon literature is great, but there are countless Penguin Random House titles that can supplement “The Classics” to help get your students excited to read new things and find new and more diverse characters through which to see the world.