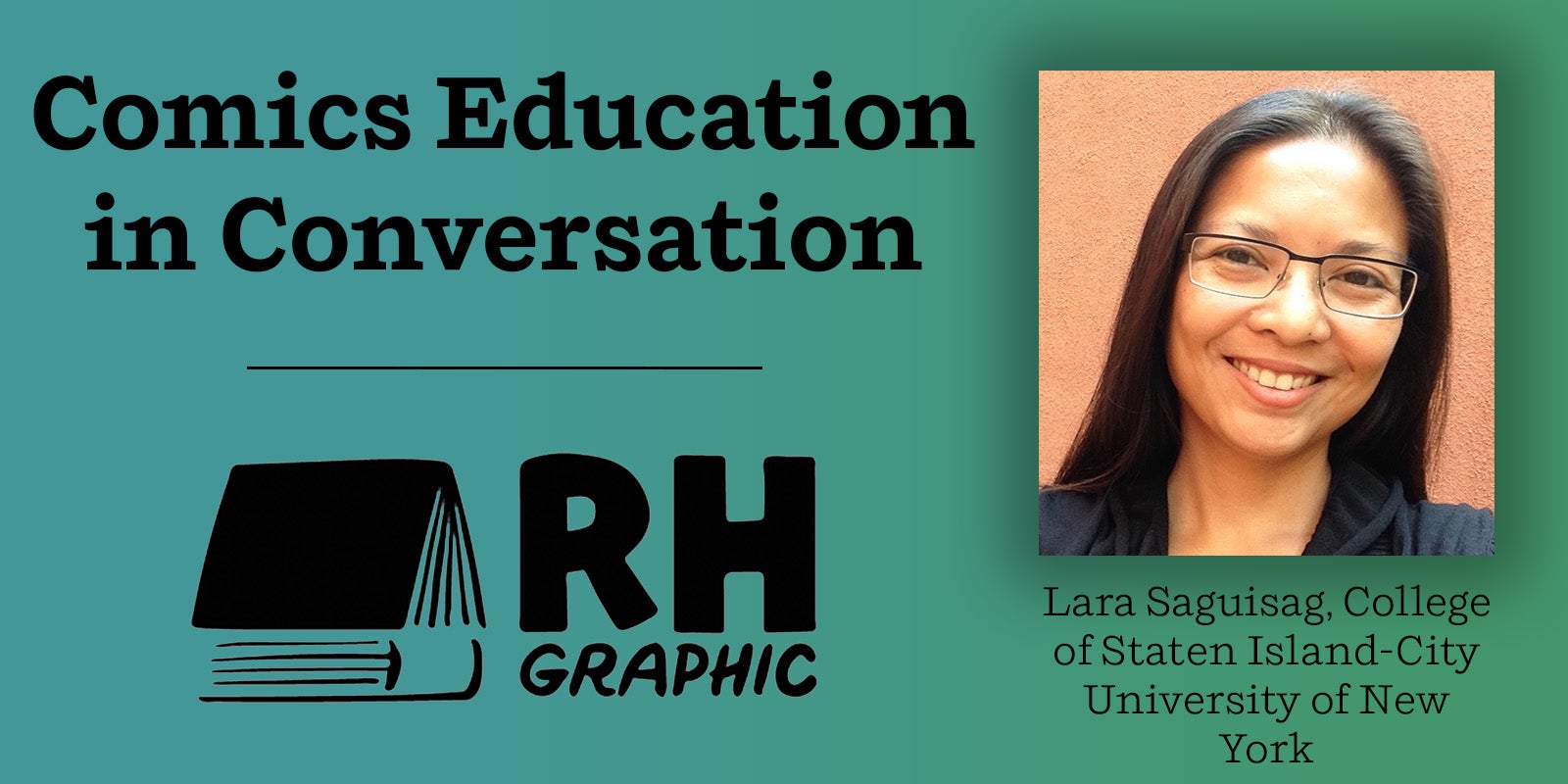

Lara Saguisag is Associate Professor of English at the College of Staten Island-City University of New York. Her book Incorrigibles and Innocents: Constructing Childhood and Citizenship in Progressive Era Comics (Rutgers UP, 2018) received the Charles Hatfield Book Prize from the Comics Studies Society, the Ray and Pat Browne Award from the Popular Culture Association/American Culture Association, and an Eisner nomination for Best Scholarly/Academic Work. Her current project examines representations and roles of fossil fuel energy in children’s literature. She is currently co-editing, with Marek Oziewicz, a special issue on Children’s Literature and Climate Change for The Lion and the Unicorn. She is also a member of the Board of Directors of the Children’s Literature Association.

How did you get started reading comics?

I read a lot of komiks when I was growing up in Manila. Komiks were printed on pulp and often featured serialized fantasy/horror stories and gag strips. In my neighborhood, there was a sari-sari store (a small corner store that sold all sorts of goods) that rented out komiks for about 10 centavos an issue. The storeowners displayed the komiks by hanging them on a clothesline. I spent many weekend afternoons sitting on the bench set up outside the store, reading issue after issue.

My father was an anti-Marcos activist and he often brought home newspapers and magazines (printed by the alternative press) that featured cartoons and strips by Nonoy Marcelo. Marcelo’s comics were very critical of authoritarianism, militarism, and imperialism. So very early on, I learned that comics and cartoons had political utility.

On the other hand, it was also through my father that I learned comics can be risqué! I spent a lot of time nosing around his library, looking for stuff to read. He had dozens of paperbacks, but the ones that appealed to me most were the ones with pictures—which happened to be an anthology of Playboy cartoons and compilations of Andy Capp strips. The jokes about sex, marriage, and intoxication definitely went over my head, yet I read those books cover to cover, partly because I felt a thrill reading these “forbidden” texts.

The Adventures of Tintin and Asterix were the first comics that I owned. These two series made me realize that comics were not just stories; they were objects to collect, reread, and cherish. As an adult, I have a more ambivalent view of these comics, as they perpetuate injurious stereotypes. But I do remember how Tintin and Asterix were important to me because they gave me a sense of ownership. They also made me feel I was part of a community. For one, I bonded with my brothers, friends, and classmates because of our shared love of Captain Haddock and the puns in Asterix.

How did you get from your first comics-reading experience to doing academic work about the medium?

When I was an undergraduate student at the University of the Philippines, I befriended a few folks who were really into comics. They gave me a comics education: they introduced me to Maus, Raw, Watchmen and the work of Filipino and Filipino American cartoonists. A couple of these friends ended up teaching in U.P’s Department of English and Comparative Literature and they taught courses on comics. Because of their advocacy, I never questioned the place of comics in college classrooms.

I moved to the U.S. for graduate school. While I’ve encountered some resistance to the study of comics in U.S. institutions, I was fortunate enough to work with various mentors who enthusiastically supported my research on topics such as the history of Wonder Woman, race and childhood in Tintin, and representations of childhood in Progressive Era comics. They championed my work and encouraged me to look for nuances in the materials I was studying. I think if they raised their eyebrows when I proposed these topics, I might have ended up working with more “traditional” texts.

Have you seen a change in the field of comics studies over the course of your career?

The first time I attended a comics conference was in 2011, nearly ten years ago. I think I was one of two women of color in attendance. I felt so alienated and uncomfortable in that space—frankly, I felt I was surrounded by White men flexing and showing off their academic muscles. When I attended the inaugural Comics Studies Society conference in 2018, I braced myself, expecting to feel isolated and invisible all over again. But the conference organizers were so attentive to the design of the event. They worked to make sure the conference was diverse, inclusive, and accessible. I was also overjoyed to see that women were well-represented in CSS leadership.

There is definitely a lot of work that needs to be done in order for comics studies to become a more equitable and just field. It remains patriarchal and Eurocentric/U.S.-centric. But I’m really delighted to see more BIPOC, women, and queer scholars and students working in comics studies. Their work is energizing comics studies: they complicate histories and theories of comics, call attention to understudied texts and neglected cartoonists, and offer exciting new readings of well-known materials.

You’re on the Board of Directors of the Children’s Literature Association (ChLA). What’s the reception of comics like in that space?

A good number of ChLA members publish innovative research on comics for children and young adults. When I participate in syllabi exchanges at ChLA, I happily note that many instructors include graphic novels in their reading lists. There are children’s literature scholars—most notably, Gwen Athene Tarbox, Michelle Abate, and Joseph Michael Sommers—who publish consistently on comics. Research and writing on comics are encouraged in ChLA. This is quite noteworthy because, as Charles Hatfield points out, many children’s literature gatekeepers and researchers have, until quite recently, considered comics to be subliterary materials.

While research in children’s comics can certainly become more robust, it’s disappointing to hear folks say that scholars are ignoring children’s comics and the connections between comics and childhood. Such statements sweep aside the body of work produced by women in comics studies and children’s literature studies. I’m hoping comics researchers can be more mindful about acknowledging and engaging with the work of folks like Gwen and Michelle as well as Maaheen Ahmed, Lan Dong, Mel Gibson, Susan Honeyman, Anuja Madan, Julia Round, Carol Tilley, and Brittany Tullis.

You wrote ‘Incorrigibles and Innocents: Constructing Childhood and Citizenship in Progressive Era Comics.’ What drew you to these comics, and this topic?

I read a lot of comics histories in college and graduate school, and I repeatedly encountered references to the Yellow Kid, Buster Brown, the Katzenjammer Kids, and Little Nemo. But I never really had a chance to read the various series in which these characters appeared. So Incorrigibles and Innocents was my attempt to engage more deliberately with these materials.

My work was certainly cut out for me. I spent hours and hours going through newspaper archives and had to read hundreds of comic strip episodes. I also had to train myself to understand jokes that were more than a hundred years old. More troublingly, I had to deal with strips and cartoons that had racist and sexist content. I had to learn how to patiently dissect these texts while also making sure that I did not become inured to the cruelty of the images and jokes that I encountered.

The project began as my dissertation. But it was more than a “thing I have to finish to earn my PhD.” It was quite urgent and personal for me. I’m an immigrant, and so researching and writing Incorrigibles and Innocents became a way for me to understand the complex and painful history of my adopted country. Writing it helped me understand the problematic way U.S. citizenship is defined—it is a definition built on exclusion and derision, that seeks to draw a line between “us” and “them.” The project also helped me recognize that early 20th century notions of citizenship still endure in the 21st century. When I was revising the manuscript in 2016, I was shaken by the fact that the vile rhetoric deployed in Progressive Era comics against Black Americans and immigrants was echoed in the Trump administration’s policies and agenda.

Tying into that, kids comics have been on the rise recently. What are you seeing changing in that space today from the era you wrote your book on?

The newspaper comics I studied were mostly produced by White men and idealized White, middle-class, heteronormative childhoods. It is exciting to see that many comics today represent diverse childhoods and are being produced by women, BIPOC, and queer, trans, and non-binary cartoonists.

Some U.S. Americans of the Progressive Era found newspaper comics to be incredibly suspect. Decades before Fredric Wertham published Seduction of the Innocent (1954), educators and reformers denounced newspaper comics as “garish” and “low-class,” arguing that newspaper comics were corrupting White, middle-class children. So it is quite interesting to see that a century later, children’s comics are prominently displayed in bookstores, nominated for high-profile awards, and featured in schools’ and libraries’ recommended reading lists. While educators in the early 20th century argued that comics reading would render children illiterate, many educators today argue that comics can help children develop their visual literacies, which are seen as essential in the digital age.

While I am thrilled that adult institutions have embraced comics, I do wonder how the “blessing” of adults has changed children’s perceptions of and encounters with comics. I imagine in the previous century, many young readers were drawn to comics because its aura of illicitness. I wonder how young people today approach comics, given that these texts, generally speaking, have received adults’ seal of approval. Maybe this means comics reading will become more of a shared experience between children and adults and less an activity that children do surreptitiously, hiding under the covers with a flashlight.

What are you working on now?

I’m currently working on a project that examines the relationship between children’s narratives and fossil fuels. In this project, I think about how nonrenewable fuels (and their industries) are represented in children’s books, comics, and media. I am also hoping to track how fossil fuels, particularly oil, figures in the production, distribution, and consumption of children’s narratives.

While majority of U.S. Americans acknowledge climate change and appear to support a shift to renewable forms of energy, we still go about business as usual. We still imagine economic growth to be infinite, boundless, and lacking in consequence. I’m hoping that my research will help show how children’s cultural forms have been used to naturalize and promote dependence on fossil fuels. These narratives that suggest that “oil is inevitable” are incompatible with the stories that young climate strikers around the world are telling.

Favorite or new graphic novel recommendations?

I love Dav Pilkey, especially his Super Diaper Baby books. I guess I enjoy toilet humor! I do find Pilkey’s work to be incredibly clever and genuinely funny. I just love the subversive energy of his books. I also love that he breaks the fourth wall and includes instructions on how to draw in his books—he looks at his young readers as active participants and even co-creators. But the best thing about being a Dav Pilkey fan is that is earns me “cool aunt” points. My seven-year-old nephew thinks highly of me because I can talk to him about Captain Underpants and Dog Man.

I’m also reading a lot of narratives about superstorms and climate catastrophe, and I’m deeply affected by Josh Neufeld’s A.D.: New Orleans after the Deluge; Don Brown’s Drowned City: Hurricane Katrina and New Orleans; and Philippe Squarzoni’s Climate Changed.