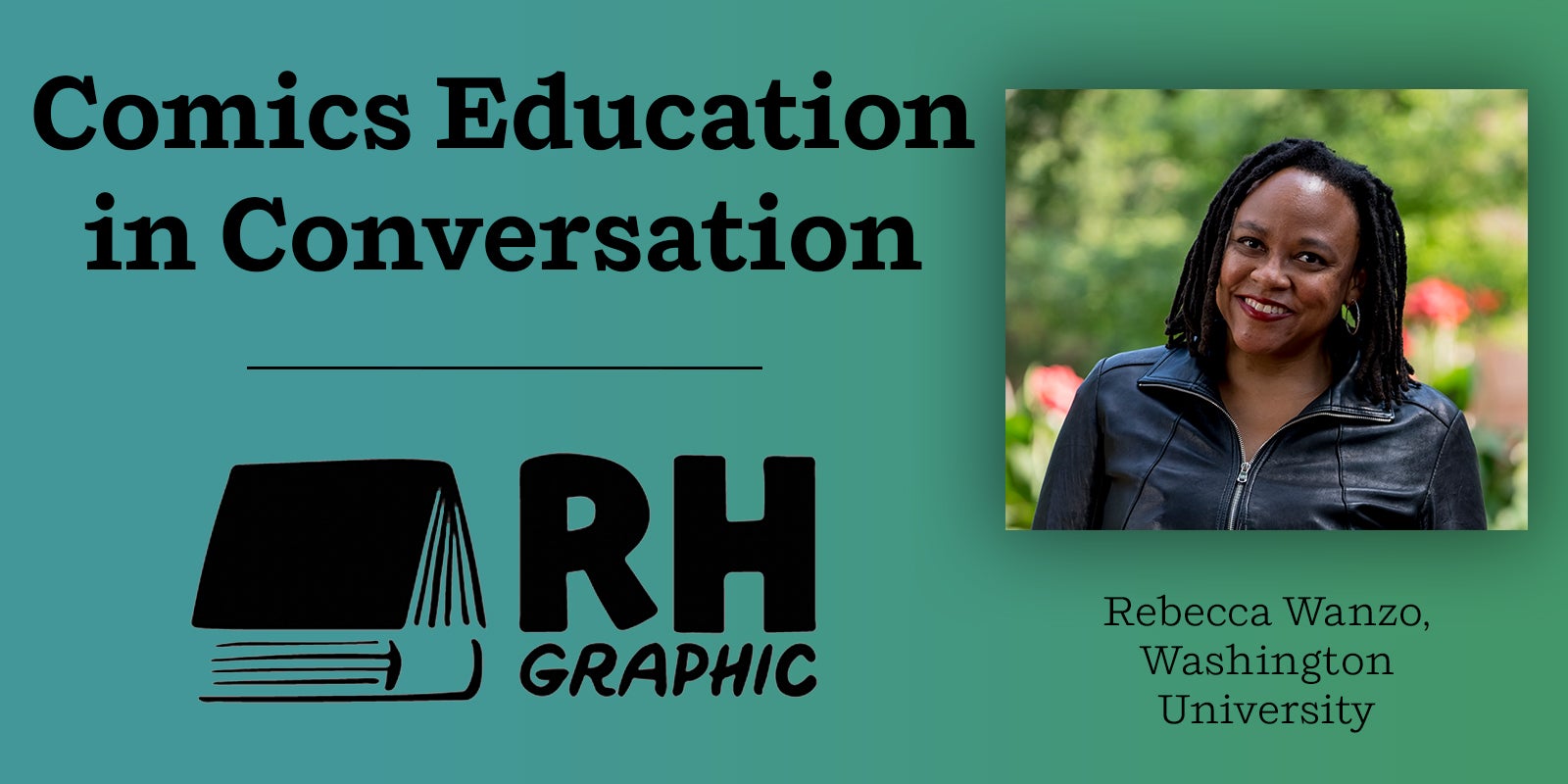

Rebecca Wanzo is a professor and chair of the Department of Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at Washington University in St. Louis. She is the author of The Suffering Will Not Be Televised: African American Women and Sentimental Political Storytelling (SUNY Press, 2009), which uses African American Women as a case study in exploring the kinds of storytelling conventions of people must adhere to for their suffering to be legible to various institutions in the United States. Her most recent book, The Content of Our Caricature: African American Comic Art and Political Belonging (NYU Press, 2020) examines how Black cartoonists have used racialized caricatures to criticize constructions of ideal citizenship, as well as the alienation of African Americans from such imaginaries.

Her research interests include African American literature and culture, critical race theory, fan studies, feminist theory, the history of popular fiction in the United States, cultural studies, theories of affect, and graphic storytelling. She has published in venues such as American Literature, Camera Obscura, differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies, Signs, Women and Performance, and numerous edited collections. She has also written essays for media outlets such as CNN, the LA Review of Books, Huffington Post, The Conversation, and the comic book Bitch Planet.

How did you get started reading comics?

I read comic strips like Bloom County as a kid but didn’t start reading comic books until I was in graduate school and wanted to read for pleasure but did not have as much time to read novels that were not related to my degree.

How did you get from your first comics-reading experience to doing academic work in the medium?

My first academic job was at Ohio State, home to (what is now called) the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum. It holds the largest collection of comics and cartoon related materials in the world. The archives there and scholars such as Jared Gardner who were in the field created a really nurturing environment for me to enter this community of scholars. My first article was about Truth: Red, White, and Black (Bob Morales and Kyle Baker), which I initially thought would be a one-off, but the archives and support at OSU led me to immerse myself in the field.

Have you seen a change in the academic or popular reception of comics and graphic novels over the course of your career?

Obviously, the field has been growing by leaps and bounds. Most academic presses have published books on comics or cartoon art, and the diversity of work that cartoonists are producing is astounding. Many writers are doing work in comics and bringing new readers. There is still a bias against it as non-substantive, which a bias that I experience as a scholar of popular media more broadly.

Your most recent book was The Content of Our Caricature: African American Comic Art and Political Belonging. What drew you to this topic?

I began with Truth, and as I read over time I realized there were some gaps in scholarship and our general understanding about the work of African American cartoonists. First, cartooning is often excluded from broader discussion of African American visual culture. While some people like Ollie Harrington and Aaron McGruder have received some attention, there are a wide range of people that no one knows. Looking at the work of Pittsburgh Courier cartoonist Sam Milai, for example, was a revelation for me. Second, I am always interested in popular representations of suffering and citizenship (that was the subject of my first book), and I started to see the ways in which many cartoonists are basically political theorist for the public sphere and felt people should engage with their thinking. And finally, I have become increasingly interested in debates about positive and negative representations of Black people, and I’m interested in when people might take unusual paths to comment on anti-Blackness—including caricature and stereotype.

Building on that, there’s long been a call for increased diversity in comics—and that’s only intensified this year. What are you seeing changing in this space today?

Well, obviously the field is much more diverse, with much more diversity in writers and creators. We still see substantial resistance to comics more inclusive of the world we live in, and I don’t think that’s going away any time soon. But I’m thrilled to see so much new work that it’s hard to keep up, and to see brilliant artists like Keith Knight get adaptations.

What are you working on now?

I just finished a draft of an essay about African American artists Charle White, Romare Bearden, Robert S. Pious, and Charles Alston and the need to consider their work as cartoonists as an important part of their work as artists. I’m doing some work on race and fan studies, and I hope this year to complete a draft of a short book about the first Black Panther film.

Favorite or new graphic novel recommendations?

There’s so much. But let me suggest that people check out the new Megascope imprint from Abrams.