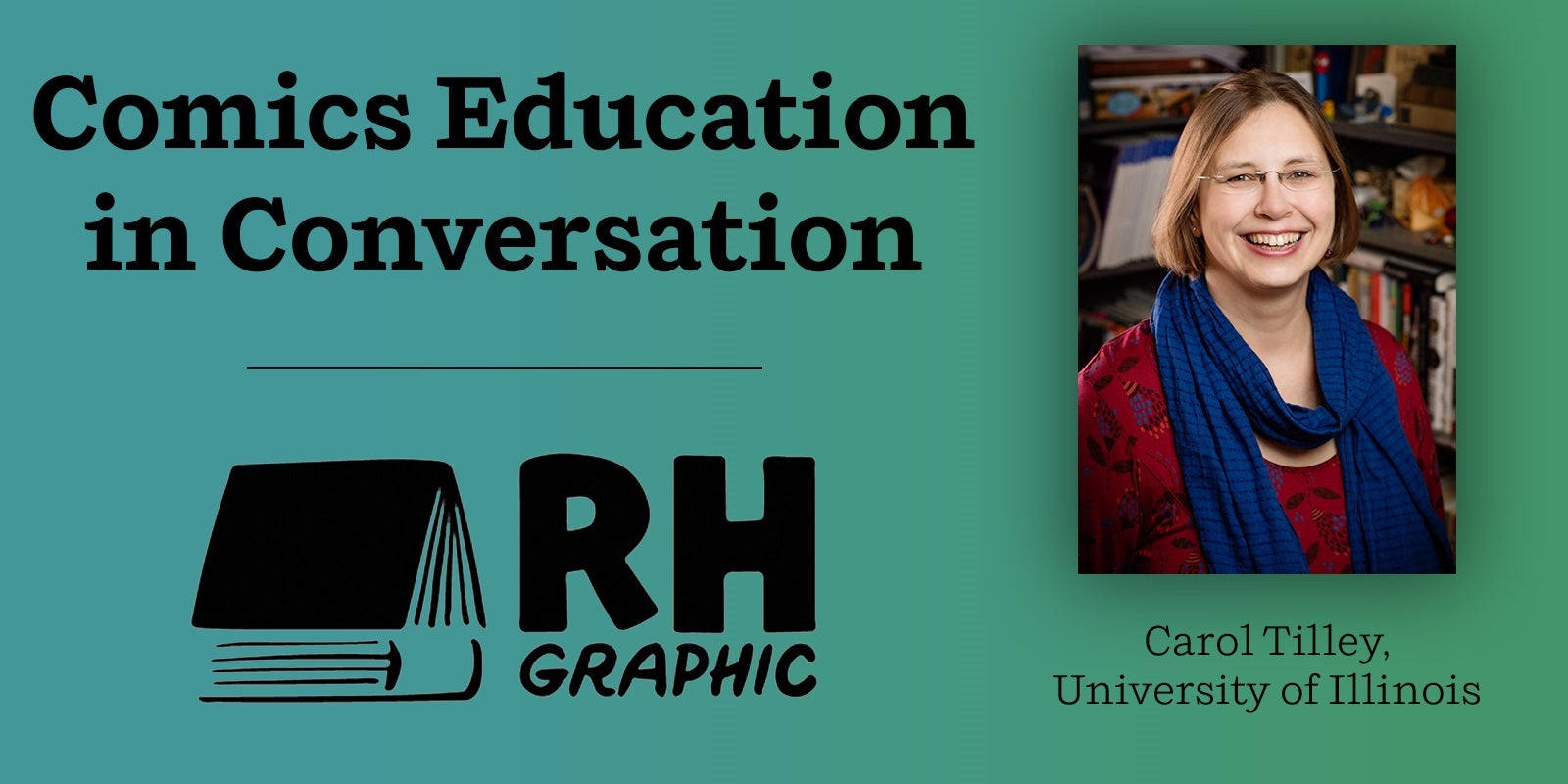

Carol Tilley (she/her), a former school librarian, is currently an associate professor in the School of Information Sciences at University of Illinois. Tilley’s comics scholarship focuses on young people’s comics readership, especially in the US during the mid-20th century. Her research on Fredric Wertham was featured in the New York Times and other media outlets. She is a founding member and past-president of the Comics Studies Society, as well as a former judge for the Eisner and Ringo Awards.

How did you get started reading comics?

I’ve been reading comics as long as I could read and even before that I stared at the images. I started off with comic strips in the daily and Sunday newspapers, fighting my dad over who got to read them first. My favorites as a young kid were Peanuts, Blondie, and Family Circus. As a teen and young adult, I grooved on Bloom County, Calvin and Hobbes, and a Speed Bump precursor Dave Coverly created for the student newspaper at Indiana University, while he was getting a graduate degree.

My grandparents bought me mountains of second-hand vintage Archie comic books at various flea markets and I enjoyed visiting my small town drug store as a kid to spend my quarters on Richie Rich, Sad Sack, and a bunch of 1970s Harvey, Charlton, and Gold Key titles.

Through college and a little beyond I was sustained mostly through comic strips. As I was in the process of coming out as lesbian in my early 20s, I found sustenance and guidance in strips like Alison Bechdel’s Dykes to Watch Out For, Diane DiMassa’s Hothead Paisan: Homicidal Lesbian Terrorist, and many of the wonderful cartoonists featured in Roz Warren’s edited collection Dyke Strippers: Lesbian Cartoonists from A to Z.

How did you get from your first comics-reading experience to doing academic work in the medium?

After finishing my undergrad degree, I completed a masters in library science and then worked as a high school librarian for a few years. I had an epiphany early on as a librarian about the disjuncture in my own childhood experience of being an avid library user and reader, but still having to go to the drug store to buy comics since there were none in the library. In the early and mid-1990s when I was a librarian that was still the case in most libraries: no comics. I started to question why that was as well as to purchase a few titles for my library’s collection.

When I went back to school to start my PhD in information science, I tried to do more conventional sorts of research, but for various reasons, I kept getting stuck. And I kept coming back to comics. In my program, doing historical work wasn’t something the school’s dean really approved of. He wasn’t really fond of anything associated—even marginally—with children. My advisor told me to go talk to him and get his blessing. I was terrified, but I was also tired of being stuck and those questions I had about comics and libraries were a way forward.

The dean turned out to be more supportive than any of us guessed. I ended up completing a dissertation that examining how librarians perceived comics in the years 1938 to 1955. Those are great years for bookmarking the ‘Golden Age’ of comic books in the US and the peak of their popularity, but they’re also important years for considering the concept of intellectual freedom as a core value of librarianship. I appreciated the overlap.

As well as a historian, you’re also a librarian educator. How are your students responding to comics?

Around 1997—early in my much-too-prolonged time as a doctoral student—I was invited to speak to a class of library and information science students who were learning about resources for young adults. I focused my time with them on comics, zines, and alternative periodicals. What struck me was how absolutely alien most of the students found this stuff.

Since 2011, I teach an annual (sometimes more frequent) course I developed on reader’s advisory for comics. Every time it’s been offered, the class fills. Although some of the students are comics novices who remain genuinely curious what all the fuss is about, many of them are avid comics readers in their own right. Webcomics and manga are their most common entry points.

It’s been really rewarding to watch so many students I’ve taught or worked with go on not only to embrace comics as a rewarding part of our cultural heritage, but also become leaders in librarianship’s continuing acceptance of comics.

Have you seen a change in the academic, library, or popular reception of comics and graphic novels over the course of your career?

Enormous changes! As I was really starting to dive into reading and thinking about academic work on comics in the 1990s, comics studies in the US was driven by a lot of white guys, some of whom were peripheral to academia. A lot of that early-ish scholarship by folks like Tom Inge, Rusty Witek, Charles Hatfield, Tom Andrae, and John Lent remains integral to comics studies and I have great admiration for it. In 2018 when I was president of the Comics Studies Society (an organization I couldn’t have dreamed of even a decade earlier), I helped host its first conference. There were still white guys from literature departments in attendance, but we had equal numbers of women and nonbinary folks, queer, Black, brown and Asian scholars. Plus the disciplinary representation included folks from fields like philosophy, religion, art history, disability studies, queer studies, biology, and design. Even better, we had librarians, archivists, clinicians, and cartoonists there too! Our 2019 conference in Toronto, co-hosted by Candida Rifkind and Andrew O’Malley, was even more spectacularly diverse.

For librarianship, we have the wonderful Graphic Novels and Comics Roundtable via the American Library Association, regularly comics programming at conferences, and professional journals that review comics and graphic novels. It’s only going to get better.

You’ve done academic work on Frederic Wertham and the discrepancies between his research and what he reported. Can you talk a little more about this work, and what drew you to it?

I can’t say that I was drawn to Wertham. When the Library of Congress opened his archival materials to the public in 2010, I made a trip to view some of the 200+ boxes there. His anti-comics work in the 1940s and 1950s is an inescapable part of the broader narrative of comics history in the US and, to some extent, globally. Various passages in his 1954 Seduction of the Innocent note correspondence with librarians and teachers and that was what I went seeking. Within the first few hours of my time in the collection, I began to realize that there were these weird discrepancies in what children told him about their comics reading experiences and how he reported it in his book.

In 2010 and 2011, I made several trips to look at the collection, photographing, scanning, and copying materials. I was intrigued by the voices of these quite real kids: that is what got me hooked. And because the kids drew me in, I finally realized I needed to help tell their sides of the Wertham story. Many of these kids were his psychiatric patients and for me, the discrepancies in the record amounted to an abuse of trust and power. After more than 50 years, they needed to be heard.

Wertham didn’t lie or invent everything he wrote. He did, however, embellish and distort a lot of the underlying cases; alternately, he was skilled at omission. Frequently he changed ages by a year or more, altered the names of comics or types of comics kids read, left out key context. For instance, Wertham might present a child as an 11-year old patient at his clinic, whose crime comics reading led him to beat up a playmate indiscriminately. In reality, this child may have been a couple of years older and known to Wertham only via a brief report shared by an acquaintance of a colleague. Wertham might fail to note anything about the segregated and impoverished circumstances in which the child lived or the medical conditions he had or that he most enjoyed reading comics like Superman because the superheroes helped catch the bad guys.

You’re now studying young people’s comics readership and participation in fan culture. Can you tell us a little more about this? I know it’s still in progress.

Comics were more popular among kids and teens during the 1940s and 1950s than video games are among today’s young people. Comics readership surveys during these decades found that more than 95% of all elementary school-aged children read comic books and comic strips regularly. More than 80% of teens read comics regularly and many adults did as well. There was little difference in readership based on gender, race, intellect, or socioeconomic levels. More than 80% of teens read comics regularly and many adults did as well. The combined readership pushed sales of comics to more than one billion new issues annually in the US alone by the early 1950s and made comics in newspapers the most popular section.

But the cool thing is that a lot of kids were doing more than just ‘reading’ comics. They were using comics as ways of building social networks, developing writing and cartooning avocations, challenging the social status quo, and so much more. Through lots of deep archival work, dives in old newspapers, and even some interviews, I’ve begun assembling what I think is a really incredible story about how young people took used and subverted these accessible, abundant cultural commodities we think of as comics to create their own vibrant youth-focused print culture. I’ve been able to share some of these stories in papers and conference talks, but I look forward to sharing these stories in book form.

Favorite or new graphic novel recommendations?

I’m an avid reader, so I spend (maybe) too much time reading and thinking about comics, making it hard to pick only a few.

- Necessary subscription: The Nib’s quarterly comics magazine.

- Memoir for teens and older: Joel Christian Gill’s Fights: One Boy’s Triumphs Over Violence.

- Biography: Isabel Quintero and Zeke Peña’s Photographic: The Life of Graciela Iturbide.

- Makes me smile: Laura Knetzger’s Bug Boys.

- Escape: Rob Guillory’s Farmhand

- I might have cried: Tom Haugomat’s Through a Life

SOCIAL MEDIA

Twitter: @anuncivilphd

Website: www.caroltilley.net

Media Profile: https://www.womensmediacenter.com/shesource/expert/carol-l-tilley-phd

Facebook Page I We Need Diverse Comics: https://www.facebook.com/WeNeedDiverseComics