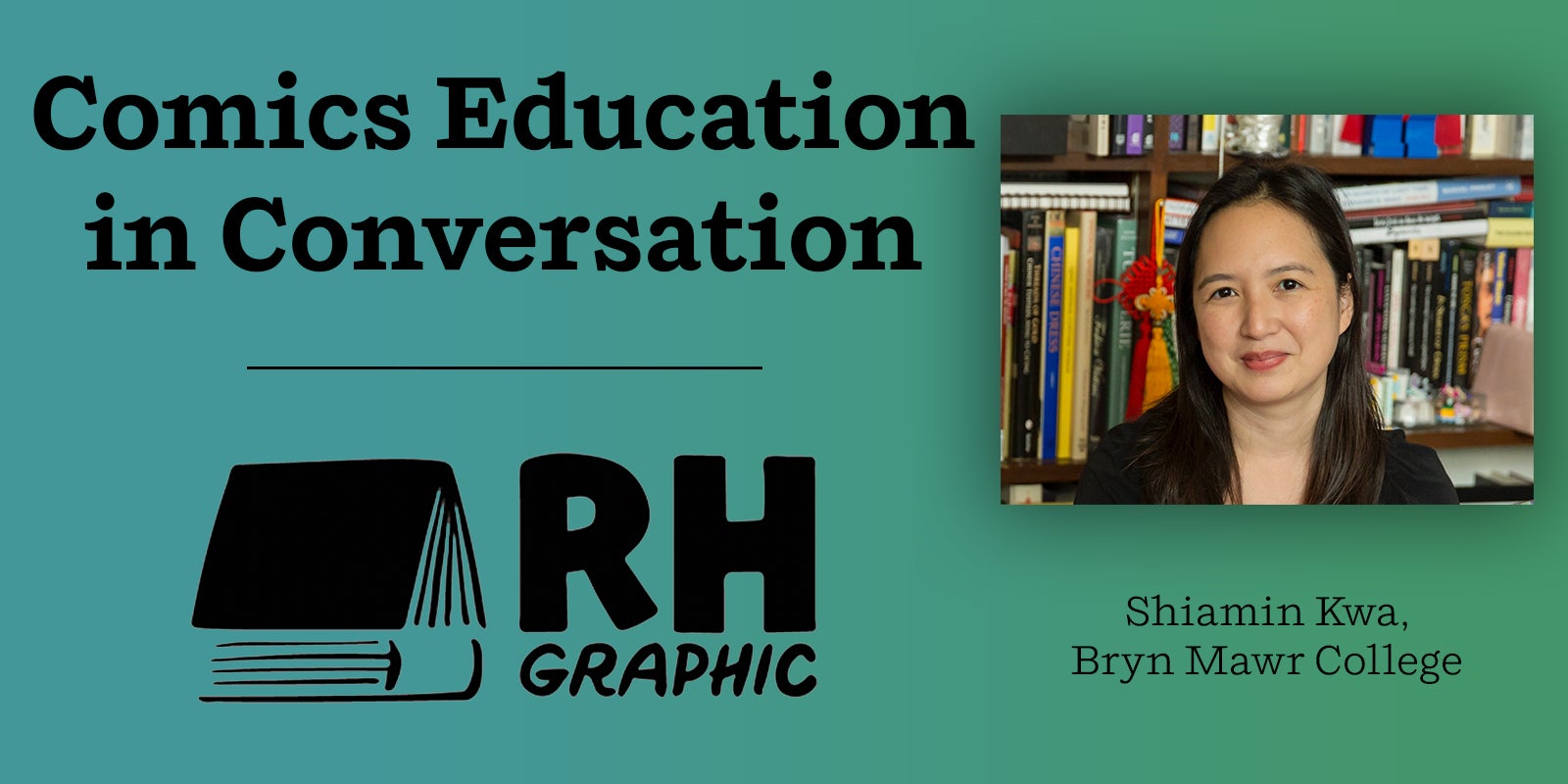

Shiamin Kwa is Associate Professor and Chair of East Asian Languages and Cultures and Comparative Literature at Bryn Mawr College. She received her M.A. and Ph.D. in Classical Chinese Literature from Harvard University and her B.A. in English Literature from Dartmouth College. She is the author of Regarding Frames: Thinking with Comics in the Twenty-First Century (RIT Press).

How did you get started reading comics?

I grew up in Malaysia. I would go to the corner store with my grandfather where he would go to get his newspaper. He would buy me comics and candy. I would get UK comics like The Beano and The Dandy, and also US comics like Richie Rich comics and Uncle Scrooge.

How did you get from your first comics-reading experience to doing academic work in the medium?

At Harvard I studied fiction and drama from China’s late imperial period (14th-19th-Century), Italian and French opera, and literary theory. But what interested me about Chinese and European opera was the way that different art forms like poetry and music tell stories, and how they tell them together. Comics are another instance where words and image are working together and sometimes working apart, and I am really interested in the moments where a reader really feels that tension. When I started reading Michael DeForge’s comics, I felt like I was witnessing something extraordinary and I was so excited about it. As an academic, my instinct is always to see what other people have to say, to see if I can find my people. I searched and found reviews, but nothing academic, so I decided to write the article I wanted to read, which I did for Word & Image. Once I did that, I just could not stop!

Have you seen a change in the academic and/or popular reception of comics and graphic novels over the course of your career?

Yes, definitely. Just yesterday, one of my dear colleagues, a scholar of Spanish literature, announced at a student and faculty gathering that Sabrina by Nick Drnaso is her favorite graphic novel. That would have been inconceivable to me to hear in the late 90’s when I was beginning graduate school. It also makes total sense to me: people who love to read, who appreciate art in all its forms, and who spend their time thinking about big questions would be really missing out on a huge chunk of our current culture if they did not pay attention to comics.

You’ve done academic work on close readings of graphic novels – can you tell us more about that?

I believe very strongly that one of the most basic human impulses is to try to understand other people: why do they do the things they do, what do they mean when they say something this way, or do something that way? I think that we turn to art to try to make sense of our world, whether as makers or as consumers of art. I truly believe that paying attention to literature, music, and the visual arts teaches us how to be better humans. I think it teaches us to appreciate beauty and it encourages us to seek it out; and, because we are interacting with this product of another mind, it also teaches us how to appreciate other people. The teachers, theorists and critics that I admire the most are close readers. To me the practice of close reading, and to try to share that process with others through my criticism, is one small way of trying to walk other people through that process so that it is not only an appreciation of the work that I am exploring but also an opportunity for my reader to develop those same habits of seeking and understanding. I come to texts first as a reader, the act of interpretation that is based in close reading is my way of of trying to express why a given text is worth that time and attention.

Reading a graphic novel is an exhilarating challenge because it is engaging with language that is textual and visual, and I think it is a crucial skill for all of us to develop and cultivate this particular reading skill. So much of our communication is delivered in word-image form, from social media to infographics in international spaces, and it is important to keep on our toes about how to read carefully, scrupulously and critically.

There are a few specific comics creators you’ve focused on in your work – including Gabrielle Bell, Michael DeForge, Kevin Huizenga, and Laura Park. What draws you to these particular authors?

I think I was attracted to each of them for very different reasons, but the one thing that they share is an absolute clarity of vision. You just know when you see the work of one of these artists, their style is so well-developed and fully their own; they each possess a gift of making the reader feel close to the work, that there is this very particular and unique person who has made this thing in your hands. Part of the joy of writing the book was to then approach it from a position of: okay, how do terms like scale, rhythm, repetition, or perspective, play out in these works? What theoretical apparatus can help me explain what is going on in this work—I borrow from theories of music, poetry, and philosophy, anything that gets me closer to expressing the magical thing that makes me keep going back to them.

You’ve also written about digital comics! Can you tell us about what you’re finding interesting about that space?

I’m always interested in the way that artists do interesting things with form. It is always exciting to see someone taking advantage of a medium to express something that could not be done any other way. So, for example, a comic book can take advantage of the page turn to draw the reader’s attention to a shift or a surprise. The webcomic may be able to draw attention to movements that we take for granted in our daily interactions with screens—whether it is through animations or through directing how we scroll or swipe our ways through a narrative.

There’s long been a call for increased diversity in comics – and that’s only gotten more prominent. What are you seeing changing in this space today?

I am seeing lots of people—artists, publishers, and scholars—trying to make and to be the changes they want to see in the world, and lots of readers welcoming them with open arms. Seeing books like My Favorite Thing is Monsters and Joel Christian Gill’s Fights on so many “Best of” lists, and Emma Hunsinger’s “How to Draw a Horse” in The New Yorker is so exciting and, at the same time, so obvious. This is penetrating, beautiful work that speaks to everyone, as it delivers a specific, original, and beautifully rendered point of view.

Favorite or new graphic novel recommendations?

Favorites: Apart from the folks I have written about in my book and articles, I also love John Porcellino’s Perfect Example. Marlys, Maybonne and Freddie are my favorite characters (Lynda Barry): I don’t just feel like I know them, I feel like they know and understand me! Everything made by Hartley Lin. And I still love Uncle Scrooge.

New favorites: The brilliant Ben Passmore’s Sports is Hell really speaks to our times. I’m blown away by the lyrical and haunting work of E.A. Bethea. Gareth Brookes (most recently The Dancing Plague) is constantly trying out new media and finding the stories that emerge from the forms—he is a real inspiration. For kids and adults alike, I just loved Trung Le Nguyen’s The Magic Fish and Shing Yin Khor’s The Legend of Auntie Po, which are both books about immigration, reinvention, and the power (and adaptability!) of shared stories.

You can find more about Shiamin Kwa at shiaminkwa.org or @shiamin_kwa on Instagram