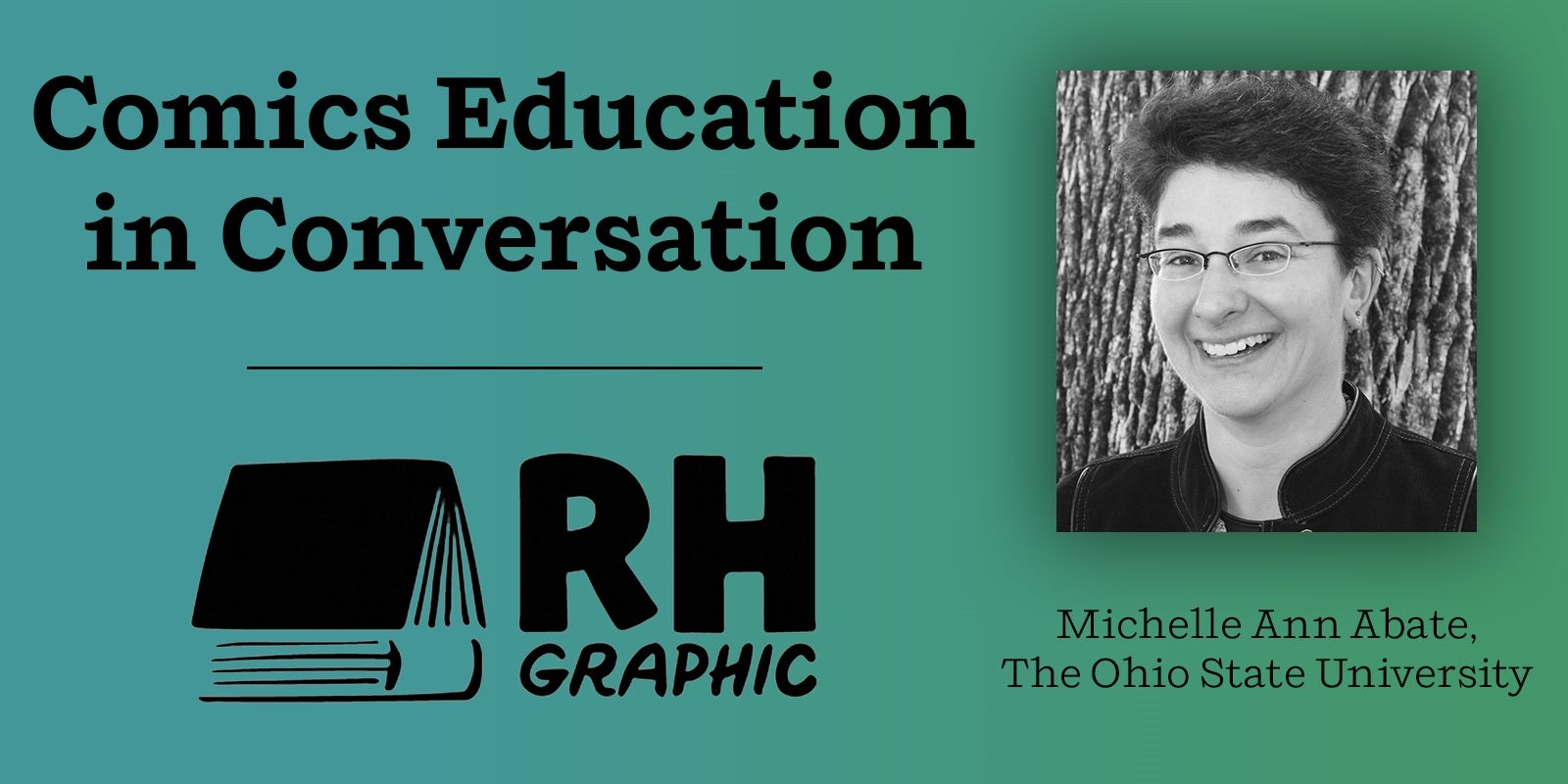

Michelle Ann Abate is Professor of Literature for Children and Young Adults at The Ohio State University. She is the author of six books of literary criticism, including Tomboys: A Literary and Cultural History (2008) which was nominated for a Lambda Literary Award. Her most recent book, No Kids Allowed: Children’s Literature for Adults, was released by Johns Hopkins University Press in 2020. Professor Abate has also published peer-reviewed journal articles about a wide array of topics, including Calvin & Hobbes, Nancy Drew, Garfield, Seinfeld, The Muppet Show, Where the Wild Things Are, The Hunger Games, Peanuts, The Far Side, and Disney’s Frozen. Additionally, Professor Abate is the co-editor of five collections of critical essays. Finally, she has written invited pieces for The New York Times, been a guest on NPR in Connecticut, and been interviewed for and quoted in articles in The Washington Post and The Boston Globe.

How did you get started reading comics?

I actually wasn’t a big reader as a young child; I was a tomboy who was always outside playing. But, I did love comics. I routinely read the strips in the newspaper, and I especially enjoyed the full-color editions on Sundays. I was fortunate to grow up during what many consider the final “golden age” of newspaper comics: the era of Calvin and Hobbes, The Far Side, The Boondocks, etc. Additionally, whenever I’d visit the local public library, I’d get paperback reprints of various strips. Charles M. Schulz’s Peanuts and Bil Keane’s The Family Circus were among my favorites. I’d borrow as many copies as the library would permit—or the spinner rack held.

How did you get from your first comics-reading experience to doing academic work in the medium?

My academic work has always involved visual narratives—film, television, art. That said, I began working with comics more consistently and seriously while I was writing my second book. I had a chapter about a series of texts that marketed themselves as a picture books, but were really political cartoons. (The first narrative was titled Help! Mom! There are Liberals Under My Bed! . . . I’m not joking.). Working on these texts got me thinking about the areas of convergence and divergence between sequential art and illustration art. It also got me back involved with comics.

Have you seen a change in the academic and/or popular reception of comics and graphic novels over the course of your career?

Absolutely. I read Art Spiegelman’s Maus in college. While the book was well-respected, it was framed as an anomaly, something rare and unusual.

Today, graphic narratives—as novels, memoirs, or works of nonfiction—are common. Moreover, they constitute some of the most commercially successful and critically acclaimed titles for young readers. From the work of cartoonists like Jerry Craft, Raina Telgemeier, and Gene Luen Yang to popularity of book series such as Amulet, Babymouse, and Dog Man, comics have wholly revamped books for young readers—a shift that I both embrace and celebrate.

You’ve done academic work with comics for kids. Can you tell us a little more about kids comics, and why they’re interesting?

Young people drive the culture in many ways. Although books, films, music, and television programs intended for kids are commonly dismissed as “childish,” they exert a tremendous influence on an era and the people who live in it—including adults. The same is true for children’s comics. When we think about the characters, plots, and titles from sequential art over the decades that have most shaped American life, it is those that were largely intended for young people: comic book superheroes like Superman, newspaper comic strips like Calvin and Hobbes, graphic novels like Smile. Kids comics are interesting for the same reason that youth culture is interesting: it is fresh, innovative, and usually iconoclastic in some way.

You’ve also written specifically on comics for girls – can you tell us a little about that?

In 2019, I published my fifth book of literary criticism. Titled Funny Girls: Guffaws, Guts, and Gender in Classic American Comics, it was the first full-length critical study to examine the important cadre of young female protagonists that permeated U.S. newspapers strips and comics books during the first half of the twentieth century. Many of the earliest, most successful, and most influential titles from this era featured elementary-aged girls as their central characters: Little Lulu, Little Orphan Annie, Nancy. My book revisits and reexamines these Funny Girls who played such a significant role in the popular appeal and commercial success of American comics during the first half of the twentieth century. In so doing, it challenges longstanding perceptions about the gender dynamics operating during this era. At the same time, remembering these feisty female figures changes our perspective on the growing presence of girls in comics during the twenty-first century. The bulk of discussions about the tremendous success of graphic novels featuring young girl protagonists like Ben Hatke’s Zita the Spacegirl, Vera Brosgol’s Anya’s Ghost, or Mariko Tamaki and Jilian Tamaki’s This One Summer cast them as a wholly new development in the field. However, these figures have strong literary antecedents. My book recoups this history and changes our understanding about our current historical moment in comics and graphic novels.

You also write about prose children’s books – is there an overlap between that and your comics work?

Without a doubt. First and foremost, young people commonly read both comics and conventional prose texts. Additionally, of course, narratives for young people have always contained visual elements as core features: picture books, board books, illustrated novels, etc. That said, the line separating comics and prose-based texts has been blurring rapidly in the past few decades. Diary of Wimpy Kid was just one of many titles that challenged such classifications: is it a graphic novel or is it prose narrative that contains lots of drawings? Indeed, Jeff Kinney created a new literary category for his work. The subtitle to Diary of a Wimpy Kid is “A Novel in Cartoons,” which—I’d argue—is not the same as a graphic novel. In the years since the release of Kinney’s series (and in large measure due to the popularity of it), a myriad of other authors and texts have likewise sought to challenge, defy, and even recreate existing literary categories.

There’s long been a call for increased diversity in comics – and that’s only gotten more prominent. What are you seeing changing in this space today? How do kids comics play into that?

Comics for young people have been at the forefront of this shift in many ways. From graphic novels like Gene Luen Yang’s American Born Chinese, Cece Bell’s El Deafo, and Jerry Craft’s New Kid to comics series such as Ms. Marvel, Lumberjanes, and Moon Girl and the Devil Dinosaur, works of sequential art for young readers have featured greater diversity than many other literary schools, styles, or formats. In many ways, in fact, I would argue that youth comics have served not simply as an important pioneer of, but powerful advocate for, this change, both in the realm of comics for adult readers and prose-based narratives for young people. The commercial success as well as critical acclaim that titles with characters who are not white, heterosexual, able-bodied, middle class, cisgendered, and Christian (to name just a few vectors of identity) have demonstrated the richness, importance, and necessity of telling different stories about different individuals who lead different lives and have different experiences and different worldviews than what has historically been the case. While the children’s book industry still has a great distance to go to cease being what librarian Nancy Larrick aptly termed the “All-White World of Children’s Literature” back in the mid-1960s, important strides have been made in the past few decades, and many of them have occurred in the realm of comics.

Favorite or new graphic novel recommendations?

I just started reading Séance Tea Party, by Reimena Yee, and I am enjoying it.