By: Ronell Whitaker

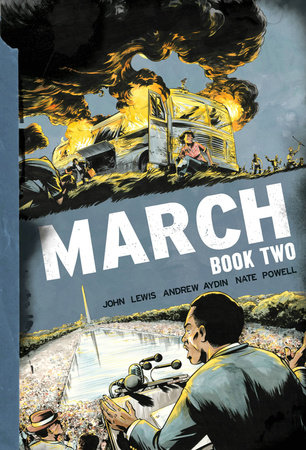

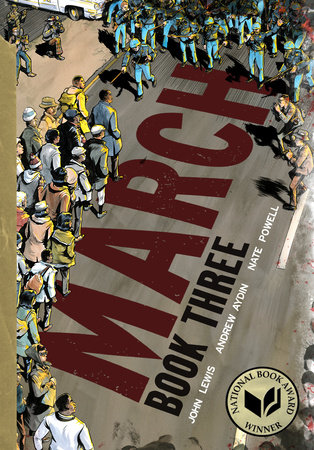

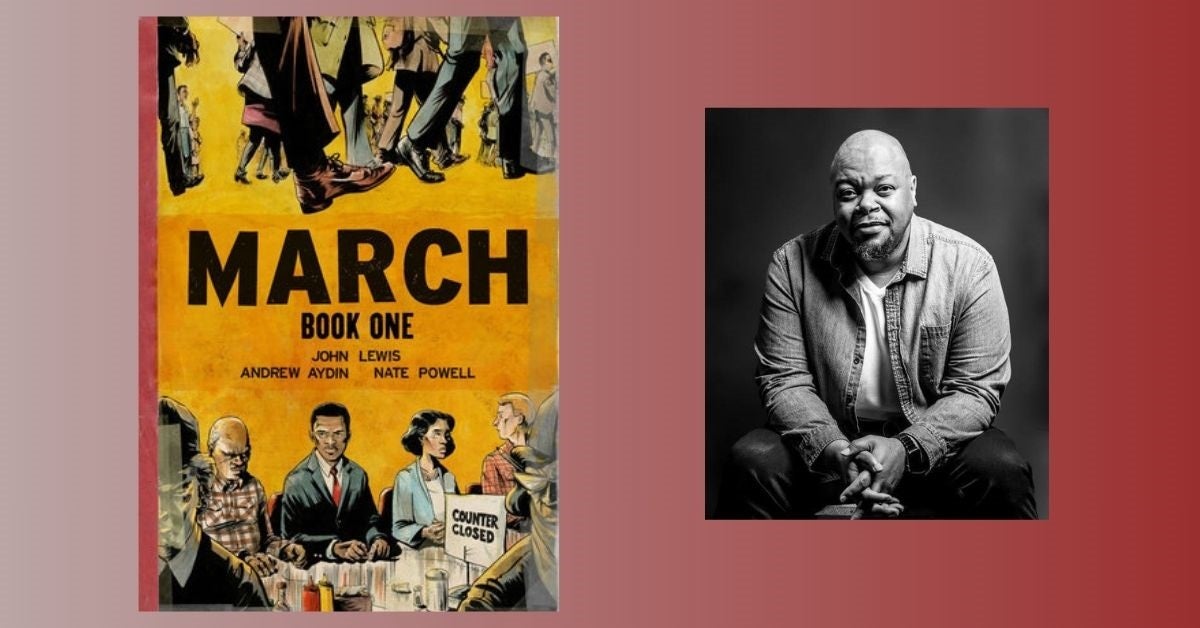

If you ask your students who Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was, you can be confident that they will spit out facts about his involvement in the Montgomery bus boycotts, or how he was a civil rights leader. Some kids may even be familiar with his “I Have A Dream” speech or “Letters From a Birmingham Jail.” Ask who Rosa Parks was, and many of your students may say she helped start the Montgomery bus boycotts by refusing to give up her seat at the front of the bus. However, if you ask your students who Bayard Rustin, Fannie Lou Hamer, Ella Baker, or John Lewis is, chances are you might get more than a few quizzical looks. When John Lewis decided to tell his story ten years ago, and to tell it in graphic novel form, he took the first step towards making sure he left an indelible mark on the world. He told his story in an accessible way to both young and old audiences and in a way that changed the world.

The biggest takeaway my students get from March is the power of telling your story, and more importantly, using that power to affect change. Since design thinking and problem-based learning has become more prominent in education, students are hungry for learning experiences that will afford them the chance to grapple with real-world problems and give them an opportunity to make a positive impact on the world around them. Using John Lewis’ early childhood as a model, students can identify and address problems in their school, community, city, or even the world, and come up with actions, no matter how small.

There is a section early on in March when Mr. Lewis’ parents intone a variation of the phrase “don’t get in trouble and stay out of the way.” This sentiment is repeated throughout Mr. Lewis childhood as the best way for Black folks to get by in America. Early on, Mr. Lewis was taught that there was no way to change how Black people were treated. That the problem was too big. That he should just stay out of the way and not get in trouble.

As his story in March unfolds we get to see Mr. Lewis journey from a young aspiring preacher (and compassionate chicken farmer) to the civil rights and legislative hero we know today. We see young John face the inequalities of growing up in a system that is designed to subjugate him, and we see him grapple with how to change that system. We are along for the ride as John takes his first steps into activism and peaceful protest, and we witness the dangers along with the triumphs. We see why it was imperative that John put himself in the way and got into the kind of trouble that could move mountains.

It’s moments like those that make it more evident why comics are the best medium for telling stories like that of the Civil Rights Movement. Beyond the visual nature of the medium, March also capitalizes on some of the hallmarks we tend to associate with comics in general. There’s bravery to be found in abundance with every day people depicted fighting for what’s right. There’s the Herculean strength and resolve of protestors standing up in the face of bodily harm. And all too often, there’s the self-sacrifice in service of others from the countless people who lost their lives in the struggle. If you’ve ever read a superhero comic, you recognize the parallels between the heroism of the capes and tights crowd and the heroic actions of the folks in the Civil Rights Movement as they are portrayed in this book.

As we celebrate the ten-year anniversary publication of March, there’s an even bigger reason why comics are the best medium for telling this extraordinary story. We don’t read comics just to be entertained by superhuman acts of daring and action-packed fights. The real reason we read comics is to see the best of what humanity can be, and to aspire to that height ourselves. John Lewis is a hero we can emulate, and dare I hope, be even better than. It’s at this junction of superhero sensibilities and reality that we see Mr. Lewis presenting a mirror version of Dr. King’s famous quote: if first we March, then someday we may even fly.

Ronell Whitaker is a high school English curriculum director in Chicago, IL with over fifteen years of experience and is a champion for comics in the classroom. He is a founding member of the Lit-X teacher cohort and a contributing creator of the

Ronell Whitaker is a high school English curriculum director in Chicago, IL with over fifteen years of experience and is a champion for comics in the classroom. He is a founding member of the Lit-X teacher cohort and a contributing creator of the