From the Introduction:

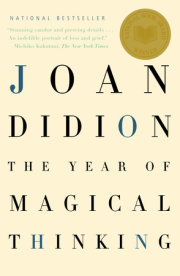

“My only advantage as a reporter,” Joan Didion explained in

Slouching Towards Bethlehem, “is that I am so physically small, so temperamentally unobtrusive, and so neurotically inarticulate that people tend to forget that my presence runs counter to their best interests.” For awhile there back in the bliss of acid and guitars, she was practically counterrevolutionary, a poster girl for anomie, wearing a bikini but also a migraine to the bon- fires of the zeitgeist. Then as the essays and novels and screenplays proliferated, she turned into a desert lioness of the style pages, part sybilline icon and part Stanford seismograph, alert on the faultlines of the culture to every tremor of tectonic fashion plate. She seemed sometimes so sensitive that whole decades hurt her feelings, and the prose on the page suggested Valéry’s “shiverings of an effaced leaf,” as if her next trick might be evaporation. But always anterior to the shiverings and effacements, the staccatos and crescendos in an echo chamber of blank uneasiness, there was a pessimism she appeared to have been born to, a hard-wired chill. Of the glum T. S. Eliot, Randall Jarrell once said that he’d have written

The Waste Land about the Garden of Eden. Likewise it was possible to imagine Didion bee-stung by blue meanies even at Walden Pond.

Still, just because Eliot felt bad most of the time doesn’t mean he didn’t get it exactly right about water, rock and the Unreal City. So was Didion on pure Zen target.

We were neophytes together in Manhattan during the late-Fifties Ike Snooze, both published by William F. Buckley Jr. in

National Review alongside such equally unlikely beginning writers as Garry Wills, Renata Adler, and Arlene Croce, back when Buckley hired the unknown young just because he liked our zippy lip and figured he would take care of our politics with the charismatic science of his own personality. Later, ruefully, he would call us “the apostates.” So I have been reading Didion ever since she started doing it for money, have known her well enough to nod at for almost as long, have reviewed most of her books since her second novel,

Play It As Lays, even published a couple of her essays when I edited the

New York Times Book Review in the early 1970s, and cannot pretend to objectivity. While I might have taken furious exception to something she said—about Joan Baez, for instance: ‘‘So now the girl whose life is a crystal teardrop has her own place, a place where the sun shines and the ambiguities can be set aside a little while longer’’; or such condescension as ‘‘the kind of jazz people used to have on their record players when everyone who believed in the Family of Man bought Scandinavian stainless-steel flatware and voted for Adai Stevenson’’— I remain a partisan. To some degree, this is because she is a fellow Westerner, like Pauline Kael, and we have to stick together against the provincialism of the East. But in larger part it is because I have been trying forever to figure out why her sentences are better than mine or yours . . . something about cadence. They come at you, if not from ambush, then in gnomic haikus, icepick laser beams, or waves. Even the space on the page around these sentences is more interesting than it ought to be, as if to square a sandbox for a Sphinx.

And looking back, it seems to me that

The Year of Magical Thinking should not have come as a surprise. All these years, Didion has been writing about loss. All these years, she has been rehearsing death. Her whole career has been a disenchantment from which pages fall like brilliant autumn leaves and arrange themselves as sermons in the stones.

*

The most terrifying verse I know: merrily merrily merrily life is but a dream. —The Last Thing He Wanted

As early as

The White Album she had her doubts about California, but did her best to blame time instead of space, as in this much-quoted passage:

Quite often during the past several years I have felt myself a sleepwalker, moving through the world unconscious of the moment’s high issues, oblivious to its data, alert only to the stuff of bad dreams, the children burning in the locked car in the supermarket parking lot, the bike boys stripping down stolen cars on the captive cripple’s ranch, the freeway sniper who feels ‘‘real bad’’ about picking off the family of five, the hustlers, the insane, the cunning Okie faces that turn up in military investigations, the sullen lurking in doorways, the lost children, all the ignorant armies jostling in the night.

But if this geomancer of deracination can be said to have any roots at all, they are here at the edge, on the cliff. She is usually, if not more forgiving, then at least bemused. “Love and death in the golden land” has been one of her themes. Los Angeles she has described as “a city not only largely conceived as a series of real estate promotions but largely supported by a series of confidence games, a city currently afloat on motion pictures and junk bonds and the B-2 Stealth bomber.” In Hollywood, “as in all cultures in which gambling is the central activity,” she would find “a lowered sexual energy, an inability to devote more than token attention to the preoccupations of the society outside.” And there is so much everywhere else: lemon groves and Thriftimarts; tumbleweeds and cyclotrons; Big Sur and Death Valley; Scientologists, Maharishis, and babysitters who see death in your aura; where “a boom mentality and a sense of Chekhovian loss meet in uneasy suspension; in which the mind is troubled by some buried but ineradicable suspicion that things had better work here, because here, beneath that immense bleached sky, is where we ran out of continent.”

Then look what happened when she returned to these roots in

Where I Was From, a book of lamentations entirely devoted to California dreamtime—to crossing stories and origin myths like the Donner Party and the Dust Bowl; to railroads, oil companies, agribiz and aerospace; to water rights, defense contracts, absentee owners and immigration; to such novelists as Jack London and Frank Norris, such philosophers as Josiah Royce, and such painters as Thomas Kinkade; to freeways, strip malls, meth labs, San Francisco’s Bohemian Club, Lakewood’s Spur Posse, and a state legislature that spends more money on California’s prisons than it does on its colleges. Didions have lived in California, with a ranchero sense of entitlement, since the middle of the nineteenth century, when Joan’s great-great-great grandmother brought a cornbread recipe and a potato masher across the plains from Arkansas to the Sierras. As a nine-year-old girl scout Joan sang songs in the sunroom of the Sacramento insane asylum. As a trapped teen, she spent summers reading Eugene O’Neill and dreaming about Bennington (although she would graduate instead from Berkeley just like her melancholy father). As a first novelist with

Run River in 1963, she blamed outsiders and newcomers for paving her childhood paradise to make freeways and parking lots. But eleven books and forty years later, she decides that selling their future to the highest bidder had been a habit among the earliest Californians, including her own family. If the whole state has turned into “an entirely dependent colony of the invisible empire” of corporate and political greed, the Didions are complicit.

As usual, of course, this bad news is fun to read, in a prose that moseys from sinew to schadenfreude to incantation, with some liturgical/fatidic tendencies toward the enigmatic and oracular, seasoned sarcastically. When

Where I Was From was published in 2003, my only gripe as a reviewer was that it omitted so much she’d written about California elsewhere. Ideally, I said, there ought to be a Library of America Golden State Didion, including everything she had ever said about Alcatraz and mall culture, poker parlors and Malibu—

where horses caught fire and were shot on the beach, where birds exploded in the air—all the bloody butter on her crust of dread.

Everyman answers that plea with this omnibus. And so we see that Didion is now skeptical not only about her home state, but, like her anthropologist in

A Book of Common Prayer, about everything she thought she knew:

I studied under Kroeber at California and worked with Levi-Strauss at Sao Paulo, classified several societies, catalogued their rites and attitudes on occasions of birth, copulation, initiation and death; did extensive and well-regarded studies on the rearing of female children in the Mato Grosso and along certain tributaries of the Rio Xingu, and still I did not know why any one of these female children did or did not do anything at all.

Let me go further.

I did not know why I did or did not do anything at all.

*

Copyright © 2006 by Joan Didion. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.