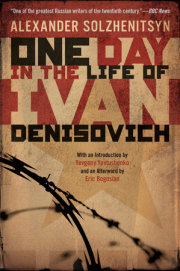

REVEILLE WAS sounded, as always, at 5 a.m.--a hammer pounding on a rail outside camp HQ. The ringing noise came faintly on and off through the windowpanes covered with ice more than an inch thick, and died away fast. It was cold and the warder didn't feel like going on banging.

The sound stopped and it was pitch black on the other side of the window, just like in the middle of the night when Shukhov had to get up to go to the latrine, only now three yellow beams fell on the window--from two lights on the perimeter and one inside the camp.

He didn't know why but nobody'd come to open up the barracks. And you couldn't hear the orderlies hoisting the latrine tank on the poles to carry it out.

Shukhov never slept through reveille but always got up at once. That gave him about an hour and a half to himself before the morning roll call, a time when anyone who knew what was what in the camps could always scrounge a little something on the side. He could sew someone a cover for his mittens out of a piece of old lining. He could bring one of the big gang bosses his dry felt boots while he was still in his bunk, to save him the trouble of hanging around the pile of boots in his bare feet and trying to find his own. Or he could run around to one of the supply rooms where there might be a little job, sweeping or carrying something. Or he could go to the mess hall to pick up bowls from the tables and take piles of them to the dishwashers. That was another way of getting food, but there were always too many other people with the same idea. And the worst thing was that if there was something left in a bowl you started to lick it. You couldn't help it. And Shukhov could still hear the words of his first gang boss, Kuzyomin--an old camp hand who'd already been inside for twelve years in 1943. Once, by a fire in a forest clearing, he'd said to a new batch of men just brought in from the front:

"It's the law of the jungle here, fellows. But even here you can live. The first to go is the guy who licks out bowls, puts his faith in the infirmary, or squeals to the screws."

He was dead right about this--though it didn't always work out that way with the fellows who squealed to the screws. They knew how to look after themselves. They got away with it and it was the other guys who suffered.

Shukhov always got up at reveille, but today he didn't. He'd been feeling lousy since the night before--with aches and pains and the shivers, and he just couldn't manage to keep warm that night. In his sleep he'd felt very sick and then again a little better. All the time he dreaded the morning.

But the morning came, as it always did.

Anyway, how could anyone get warm here, what with the ice piled up on the window and a white cobweb of frost running along the whole barracks where the walls joined the ceiling? And a hell of a barracks it was.

Shukhov stayed in bed. He was lying on the top bunk, with his blanket and overcoat over his head and both his feet tucked in the sleeve of his jacket. He couldn't see anything, but he could tell by the sounds what was going on in the barracks and in his own part of it. He could hear the orderlies tramping down the corridor with one of the twenty-gallon latrine tanks. This was supposed to be light work for people on the sick list--but it was no joke carrying the thing out without spilling it!

Then someone from Gang 75 dumped a pile of felt boots from the drying room on the floor. And now someone from his gang did the same (it was also their turn to use the drying room today). The gang boss and his assistant quickly put on their boots, and their bunk creaked. The assistant gang boss would now go and get the bread rations. And then the boss would take off for the Production Planning Section (PPS) at HQ.

But, Shukhov remembered, this wasn't just the same old daily visit to the PPS clerks. Today was the big day for them. They'd heard a lot of talk of switching their gang--104--from putting up workshops to a new job, building a new "Socialist Community Development." But so far it was nothing more than bare fields covered with snowdrifts, and before anything could be done there, holes had to be dug, posts put in, and barbed wire put up--by the prisoners for the prisoners, so they couldn't get out. And then they could start building.

You could bet your life that for a month there'd be no place where you could get warm--not even a hole in the ground. And you couldn't make a fire--what could you use for fuel? So your only hope was to work like hell.

The gang boss was worried and was going to try to fix things, try to palm the job off on some other gang, one that was a little slower on the uptake. Of course you couldn't go empty-handed. It would take a pound of fatback for the chief clerk. Or even two.

Maybe Shukhov would try to get himself on the sick list so he could have a day off. There was no harm in trying. His whole body was one big ache.

Then he wondered--which warder was on duty today?

He remembered that it was Big Ivan, a tall, scrawny sergeant with black eyes. The first time you saw him he scared the pants off you, but when you got to know him he was the easiest of all the duty warders--wouldn't put you in the can or drag you off to the disciplinary officer. So Shukhov could stay put till it was time for Barracks 9 to go to the mess hall.

The bunk rocked and shook as two men got up together--on the top Shukhov's neighbor, the Baptist Alyoshka, and down below Buynovsky, who'd been a captain in the navy.

When they'd carried out the two latrine tanks, the orderlies started quarreling about who'd go to get the hot water. They went on and on like two old women. The electric welder from Gang 20 barked at them:

"Hey, you old bastards!" And he threw a boot at them. "I'll make you shut up."

The boot thudded against a post. The orderlies shut up.

The assistant boss of the gang next to them grumbled in a low voice:

"Vasili Fyodorovich! The bastards pulled a fast one on me in the supply room. We always get four two-pound loaves, but today we only got three. Someone'll have to get the short end."

He spoke quietly, but of course the whole gang heard him and they all held their breath. Who was going to be shortchanged on rations this evening?

Shukhov stayed where he was, on the hard-packed sawdust of his mattress. If only it was one thing or another--either a high fever or an end to the pain. But this way he didn't know where he was.

While the Baptist was whispering his prayers, the Captain came back from the latrine and said to no one in particular, but sort of gloating:

"Brace yourselves, men! It's at least twenty below."

Shukhov made up his mind to go to the infirmary.

And then some strong hand stripped his jacket and blanket off him. Shukhov jerked his quilted overcoat off his face and raised himself up a bit. Below him, his head level with the top of the bunk, stood the Thin Tartar.

So this bastard had come on duty and sneaked up on them.

"S-854!" the Tartar read from the white patch on the back of the black coat. "Three days in the can with work as usual."

The minute they heard his funny muffled voice everyone in the entire barracks--which was pretty dark (not all the lights were on) and where two hundred men slept in fifty bug-ridden bunks--came to life all of a sudden. Those who hadn't yet gotten up began to dress in a hurry.

"But what for, Comrade Warder?" Shukhov asked, and he made his voice sound more pitiful than he really felt.

The can was only half as bad if you were given normal work. You got hot food and there was no time to brood. Not being let out to work--that was real punishment.

"Why weren't you up yet? Let's go to the Commandant's office," the Tartar drawled--he and

Shukhov and everyone else knew what he was getting the can for.

There was a blank look on the Tartar's hairless, crumpled face. He turned around and looked for somebody else to pick on, but everyone--whether in the dark or under a light, whether on a bottom bunk or a top one--was shoving his legs into the black, padded trousers with numbers on the left knee. Or they were already dressed and were wrapping themselves up and hurrying for the door to wait outside till the Tartar left.

If Shukhov had been sent to the can for something he deserved he wouldn't have been so upset. What made him mad was that he was always one of the first to get up. But there wasn't a chance of getting out of it with the Tartar. So he went on asking to be let off just for the hell of it, but meantime pulled on his padded trousers (they too had a worn, dirty piece of cloth sewed above the left knee, with the number S-854 painted on it in black and already faded), put on his jacket (this had two numbers, one on the chest and one on the back), took his boots from the pile on the floor, put on his cap (with the same number in front), and went out after the Tartar.

The whole Gang 104 saw Shukhov being taken off, but no one said a word. It wouldn't help, and what could you say? The gang boss might have stood up for him, but he'd left already. And Shukhov himself said nothing to anyone. He didn't want to aggravate the Tartar. They'd keep his breakfast for him and didn't have to be told.

The two of them went out.

It was freezing cold, with a fog that caught your breath. Two large searchlights were crisscrossing over the compound from the watchtowers at the far corners. The lights on the perimeter and the lights inside the camp were on full force. There were so many of them that they blotted out the stars.

With their felt boots crunching on the snow, prisoners were rushing past on their business--to the latrines, to the supply rooms, to the package room, or to the kitchen to get their groats cooked. Their shoulders were hunched and their coats buttoned up, and they all felt cold, not so much because of the freezing weather as because they knew they'd have to be out in it all day. But the Tartar in his old overcoat with shabby blue tabs walked steadily on and the cold didn't seem to bother him at all.

They went past the high wooden fence around the punishment block (the stone prison inside the camp), past the barbed-wire fence that guarded the bakery from the prisoners, past the corner of the HQ where a length of frost-covered rail was fastened to a post with heavy wire, and past another post where--in a sheltered spot to keep the readings from being too low--the thermometer hung, caked over with ice. Shukhov gave a hopeful sidelong glance at the milk-white tube. If it went down to forty-two below zero they weren't supposed to be marched out to work. But today the thermometer wasn't pushing forty or anything like it.

They went into HQ--straight into the warders' room. There it turned out--as Shukhov had already had a hunch on the way--that they never meant to put him in the can but simply that the floor in the warders' room needed scrubbing. Sure enough, the Tartar now told Shukhov that he was letting him off and ordered him to mop the floor.

Mopping the floor in the warders' room was the job of a special prisoner--the HQ orderly, who never worked outside the camp. But a long time ago he'd set himself up in HQ and now had a free run of the rooms where the Major, the disciplinary officer, and the security chief worked. He waited on them all the time and sometimes got to hear things even the warders didn't know. And for some time he'd figured that to scrub floors for ordinary warders was a little beneath him. They called for him once or twice, then got wise and began pulling in ordinary prisoners to do the job.

The stove in the warders' room was blazing away. A couple of warders who'd undressed down to their dirty shirts were playing checkers, and a third who'd left on his belted sheepskin coat and felt boots was sleeping on a narrow bench. There was a bucket and rag in the corner.

Shukhov was real pleased and thanked the Tartar for letting him off:

"Thank you, Comrade Warder. I'll never get up late again."

The rule here was simple--finish your job and get out. Now that Shukhov had been given some work, his pains seemed to have stopped. He took the bucket and went to the well without his mittens, which he'd forgotten and left under his pillow in the rush.

The gang bosses reporting at the PPS had formed a small group near the post, and one of the younger ones, who was once a Hero of the Soviet Union, climbed up and wiped the thermometer.

The others were shouting up to him: "Don't breathe on it or it'll go up."

"Go up . . . the hell it will . . . it won't make a fucking bit of difference anyway."

Tyurin--the boss of Shukhov's work gang--was not there. Shukhov put down the bucket and dug his hands into his sleeves. He wanted to see what was going on.

The fellow up the post said in a hoarse voice: "Seventeen and a half below--shit!"

And after another look just to make sure, he jumped down.

"Anyway, it's always wrong--it's a damned liar," someone said. "They'd never put in one that works here."

The gang bosses scattered. Shukhov ran to the well. Under the flaps of his cap, which he'd lowered but hadn't tied, his ears ached with the cold.

The top of the well was covered by a thick of ice so that the bucket would hardly go through the hole. And the rope was stiff as a board.

Shukhov's hands were frozen, so when he got back to the warders' room with the steaming bucket he shoved them in the water. He felt warmer.

Copyright © 1984 by Alexander Solzhenitsyn. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.