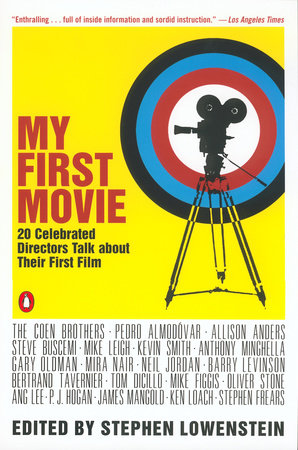

Chapter 1

Joel and Ethan Coen:

Blood SimpleWere you always passionate about movies? Did you see lots of movies when

you were kids?

JC: We always went to a lot of movies. But when we were kids it was

watching movies on TV. I guess our earliest film education came from a guy

called Mel Jazz who had a movie programme on during the days. He was an

eclectic programmer. So we were exposed to a lot of strange things-through

the eclectic programming genius of Mel Jazz. Ethan once kidded that he had

just about the whole of the Joe Levine catalogue because he'd have

812 one

day, you know, Fellini,

The Nights of Cabiria or something. And the next

day he'd have Sons of Hercules. So it was a mixture of European art films

and badly dubbed Italian muscle movies, essentially. I mean it was very

strong in that area. He also liked a lot of the golden age of late fifties,

early sixties studio comedy product. Doris Day, Rock Hudson movies. I'll

Take Sweden, you know. Bob Hope stuff.

EC: Later, bad Bob Hope.

JC: A little later on there was a film society at the University of

Minnesota that showed the kind of stuff that you wouldn't normally be

exposed to: Godard, and the Marx brothers-who were both kind of hip at the

time.

EC: I guess that doesn't exist any more. But for a period people would show

black and white 16 mm prints on some crappy projector in a basement in the

university building somewhere. I guess video ended that.

When you saw movies did you think, 'I want to do that'? I mean, you started

making films when you were kids, didn't you?

EC: Yeah. Super-8 things. But it didn't rise to the level of serious

ambition. It was another way of goofing off. I don't know when it got sort

of serious for me. Certainly later than Joel, since he went to film school

and I didn't. For me it was more an opportunity that presented itself

through Joel's work than any long-harboured ambition I'd had.

JC: But these things are sometimes just pursuing what might be a casual

interest in the path of least resistance. Even the decision to go to film

school. Something that strikes you at that moment as being a bit more

interesting than something else. It's not as if you really know what you're

going to do with it. Or if you're going to do anything with it.

EC: Yeah. There are other people you read about like Scorsese for whom it

seemed like a religion from an early age. It certainly wasn't that with

either of us.

Could you have imagined going off in a completely different direction?

EC: I never seriously thought about any career so I couldn't honestly say.

But, yeah, I suppose it could have happened.

Can you say a little about your experience of NYU film school?

JC: I think film schools are quite different now from when I went. First of

all, a lot of people on the undergraduate programme weren't really that

interested in movies. A lot of kids who had to go to college thought, this

might be fun. I'll go to film school. You know, taking the path of least

resistance. And it started that way for me. But it ended up being a fairly

interesting place to be. If you took advantage of the school's resources,

which were extremely limited but were at least something, you could go out

and make little movies and sort of screw around with it without essentially

having to pay for it beyond the tuition. I also met people there who we

ended up working with later.

What kind of films did you make there?

JC: It was just an extension of what we were doing with Super-8 cameras

when we were little kids. Just kind of screwing around. It was all pretty

crude. But even that stuff is kind of an interesting thing to have done.

When you think about people who are making a first movie, it's a little bit

different having had to look through the camera and frame a shot or imagine

how it's going to get cut together, than it is if you're coming to it from

a completely different discipline like a writer, who's never even made a

Super-8 movie and is having to figure it out intellectually. So I think it

does have some value even if what you're doing is a very crude exercise.

What happened once you got out of NYU?

JC: I started working as an assistant editor on low-budget splatter movies.

Ethan and I were both living in New York at that point and we started

writing together. We would get these writing jobs from producers who had

these low-budget movies and sometimes wanted stuff written or rewritten. We

got some writing jobs together that way at that point and that led to us

writing something to do ourselves-which was

Blood Simple.

How did the idea of writing

Blood Simple come about?

JC: We wrote a little thing for Frank LaLoggia, one of the directors I was

working for as an assistant editor; we wrote a screenplay with Sam Raimi.

So we just sat down and thought what kind of movie could we make that was

sort of producible on a really small budget like these horror movies, but

that isn't necessarily a horror film.

EC: The inspiration was these movies that Joel had been working on which

had been done mostly by young people like us who didn't have any

credentials or credibility in the mainstream movie industry. But they'd

gone out and raised money underground for their little exploitation movies,

got the movies made and subsequently wandered into the place where Joel was

working to have them cut. It was that evidence that it could be done that

led us to try it ourselves: notably Sam's movie,

The Evil Dead, because Sam

was the most forthcoming in sharing all his experience with us.

You said you chose the particular kind of story because it was manageable

at a certain budget. Was it also because you loved noir movies?

JC: On the one hand, we were both interested in and had read a lot of pulp

fiction like Cain and Hammett-and Cain especially when you think about

movies that involve murder triangles. On the other hand, as Ethan said, the

sort of financial model for the film was also, to a certain extent, a

creative influence on it. So it was kind of a mix of those two things.

EC: Also, there were a couple of notorious Texas domestic murder stories

that had just happened in the early eighties. I'm sure that figured.

Did you write from beginning to end, or did you write particular scenes

down as they came to you?

JC: We start at the beginning and work through to the end. On

Blood Simplethat was definitely the case. It was just a scene by scene accretion,

wasn't it?

EC: Right. We don't outline and we don't really know where we're going. We

might have some vague feeling that we're going to arrive at some point in

the future but it's the vaguest sort of feeling till we actually write

ourselves to that point.

But

Blood Simple's plot is so intricate, so exquisitely crafted. Is it

really just an organic process by which you arrive at such a complex

structure?

JC: Yeah. Sometimes writing yourself into a corner means that there is no

way out and you just have to bag the whole thing. But sometimes writing

yourself into a corner means that you have to think of a way out of the

corner. If you read the whole thing, you might think 'Oh this is very

intricately plotted out.' But just because, by putting yourself into a box

you figured a way out of the box, doesn't mean it was all premeditated.

Blood Simple started something else that we've done pretty much on every

subsequent movie, which was that we've always written parts for specific

actors. And as we've made more and more movies and got to know more and

more actors, they're frequently people we know personally from one place or

another or that we've worked with in the past. In

Blood Simple, we wrote

the part that Emmet Walsh played for Emmet just because we knew his work.

The other parts were written without knowing who would play them.

What's the starting point for a story like

Blood Simple? Is it a situation,

a kind of equation: a man wants his wife killed and gets killed himself? Or

a character: a slippery private eye like the character played by M Emmet

Walsh? Or is the dichotomy between plot and character a false one?

JC: It is, inasmuch as who does what to whom has to be consistent to some

sort of idea of who the characters are, even if they're rather crude. But

in this one the balance probably tips more towards the story than the

characters. I guess this one was conceived more as a thriller. I remember

that it was an early idea in

Blood Simple that someone would fake the

murder, and then do another murder that made more sense. That was there as

an equation, as you say, at some point fairly early in the writing-earlier

than the point that we got to that scene. Our initial thinking about it was

probably more about plot than about the people in it. But maybe it's just

something you just assume after the facts, since the characters in it now

seem pretty crude.

What were you doing while you were writing Blood Simple to make a living?

And how long did it take to write?

EC: I was working as a temporary clerical typist. It took a long time

because it was an evening and weekend type proposition. Months.

What did you do once you had a screenplay? You were still not 'the Coen

Brothers' as you are today.

JC: Cro-Magnon Coen brothers dragging our knuckles across the floor!

(Laughs.) We followed the example of Sam Raimi. Sam had done this trailer,

almost like a full-length version of

The Evil Dead, but on Super-8. He

raised sixty or ninety thousand dollars that way, essentially by taking it

around to people's homes to find investors. He financed the movie using a

common thing that people making exploitation movies had used, which was a

limited partnership. This was a business model taken from Broadway shows

where the general partners were the people who were producing or making the

movie and the limited partners were just individual investors who were

putting in a certain amount of money and buying equity in the product. So,

Sam also told us how to set that up and we did that in conjunction with a

lawyer here and then went out and shot a two-minute trailer in 35 mm.

Can you describe the trailer?

EC: Well, it was rather abstract, as it had to be. We didn't have the

actors: we didn't know who the actors would be, of course. Actually, what

we also borrowed from Sam and the other models was that it was presented

more as an action-exploitation type movie than it ended up being, and in

fact than we knew it would be. It was pretty much of its time. In the early

eighties there was a real vogue for these low-budget horror movies, some of

which did really well commercially and made their investors lots of money.

So we were passing ourselves off as one of those-which to a certain extent

we were, of course; but to a certain extent we were not. And we just

ignored the respects in which we were different.

JC: The trailer emphasized the action, the blood and guts in the movie. It

was very short. We had a very effective soundtrack, which is very cheap to

do. And we schlepped that around for about a year to people's homes and

projected it in their living rooms and then got them to give us money to

make the movie.

EC: The thing is when you're trying to attract someone who might invest,

you have this legal prospectus which is really dry. It's worse than

dry-it's a document that's basically warning them off the investment,

presenting all the risks. You have to be able to show them something that's

a little more intriguing than the legal document that they're eventually

going to have to sign. Which was Sam's rationale for doing his little

featurette.

JC: There were two or three people that we knew or who were connected to

our family somehow. But beyond that, they were all people we'd never met

before in our lives. If you call people up and you say, 'Can you give me

ten minutes so I can present an opportunity to invest in a movie?', they're

going to say, 'No, I don't need this', and hang up the phone. But it's

slightly different if you call up and say, 'Can I come over and take ten

minutes and show you a piece of film?' All of a sudden that intrigues them

and gets your foot in the door. That's something Sam made us wise to which

was invaluable in terms of being able to raise the kind of money we were

trying to raise, which was essentially much more money than Sam had. He'd

raised about ninety grand initially and we were trying to raise a threshold

of five hundred and fifty and up to seven hundred and fifty.

How much did you raise?

EC: Seven hundred and fifty ultimately. We started actually working on the

movie once we'd raised the five hundred and fifty.

This was all going on in New York?

JC: New York, Minneapolis and Texas.

Because you were going to shoot in Texas?

JC: Right. And because we knew some people. I think there ended up being

about sixty-five investors in the movie, most of them in five- or

ten-thousand-dollar increments. I think sixty to seventy per cent of them

were from Minneapolis.

EC: The good thing about Minneapolis is those horrible phone calls you have

to make to people you don't know-you've just got their names from whoever.

They're too polite to hang up.

JC: That's absolutely true. In New York, they'd just go, 'Yeah, yeah', and

hang up; because the dangerous thing with any salesman is to keep talking

to them. (Laughs.)

EC: But people actually put up with us! We'd walk into their living room

with our projector and before they'd even offered us to sit down we'd be

like finding the outlet, sticking the cord in, setting the projector up and

opening up the screen. (Laughs.) There was one investor we went to and we

hit his car, parking. And we had this big debate out on the driveway

whether we should tell him we hit his car before the sales pitch or after

the sales pitch. We decided that we wouldn't tell him until we showed him

the movie and made the sales pitch.

JC: Obviously he didn't end up investing in the movie!

What kind of people did end up investing in the movie?

JC: Not professional people, by and large. They weren't doctors and lawyers

and dentists and that sort of thing. They were small business people,

entrepreneurs who had started a small business themselves twenty years

earlier with very little money and had made a lot of money doing it and

related to the entrepreneurial aspect of it. They liked the show business

thing but that was actually secondary. It was more that they related to the

enterprise of just going out and trying to start a business that way. And

that's where most of the money came from. These people owned little

businesses. You know-I've got a business that supplies hair driers to

beauty salons or I've got a scrap-metal yard or I've got fifteen bowling

alleys or something like that. It's those kind of people.

EC: Fargo was based around our fascination with the Minneapolis business

community.

JC: Right. It was raising money for Blood Simple that we met all these

business guys who could wear the suits, get bundled up in the park and slog

out in the snow and meet us in these, like, coffee shops. We came back to

that whole thing in Fargo, the car salesman, the guy who owns the bowling

alley, you know, whatever. That was very much part of it.

And your family helped you out?

EC: They put in fifteen. I don't know why. I don't know why anyone did at

the end of the day.

Did the investors make their money back?

JC: Oh yeah. It took a while though.

EC: In fact it took so long that they might have done almost as well

putting the same amount of money in the bank and collecting bank interest.

But you know, they certainly did fine. And most of them were quite pleased

because it is an interesting thing to follow if you're not in the movie

business.

Did you try to raise money from any distribution companies?

JC: We went to certain people after we'd raised a certain amount of money

hoping to bring in a partner who could basically end the agony of having to

go out and find all that money-because it just took for ever. Each time

they either wanted too much or it seemed they'd be interfering and

controlling and at the end of the day it would be better to struggle on and

control it all ourselves than it would be to relinquish any control to

these groups. They all wanted to talk about the script. I'm sure they would

have taken us to the cleaners. Not that that was such an issue at that

point.

EC: It would have been complicated since we already had investors who'd

signed up under terms which forbade us being taken to the cleaners.

How long did it take between finishing the script and raising the money?

JC: It must have been at least a year and half.

Did you ever think you weren't going to make it?

JC: Oh yeah. Until we had raised the threshold amount that we needed to

start the production, neither of us thought that it was anything but a long

shot, that we'd actually succeed in doing it. I think we thought there was

a good chance it wouldn't work out.

Do you think first-time film-makers have to have a kind of crazy faith in

what they're doing because if they looked rationally at the odds they'd

never try?

JC: That's definitely true. All the things we didn't know are what enabled

us to do it and be successful. If we knew what we know now or even what we

knew when we finished the process we probably wouldn't have attempted to do

it or at least attempted it that way. The odds of succeeding at it are very

slim and the process is very difficult. That's why it's kind of hard to

recommend it to people.

EC: Right. There is something a little unhealthy about the monomaniacal

frame of mind you have to put yourself in. Right after we got it done we

kidded that the reason we got it done was because we got ourselves so

deeply in debt that the only way to pay back the money was to make the

movie.

JC: We ended up getting dangerously in debt just to live and to keep the

operation going. There was absolutely no way we could have made good on

that money without actually making the movie and have the movie make money

and pay off. So it's all a little crazy. It's all something that's a lot

easier for people who were in our position than it is for people who are a

little bit older or have financial responsibilities. We didn't have kids.

We were just kids. We didn't have any commitments so we could gamble that

way. People who are making a lot of money doing commercials or videos or

that sort of thing, a year or a year and a half into the process that we

went through, they're factoring in all the income they've lost, thinking

'Jesus!' We weren't doing that.

EC: It's an irony that even back then some of our peers were actually

making serious money at serious movie industry jobs. They wouldn't have

done what we did because they did have something to lose. They would have

to relinquish something in order to embark on something like that.

Once you'd raised the money, how did you begin to prepare for the filming?

JC: The first thing we did was hire Mark Silverman who we'd gone to school

with and I'd been to NYU with.

EC: Mark actually did have a little experience. He'd done a couple of

really low-budget horror movies.

What was his role?

JC: He was the line-producer. And he was really the one who put the movie

together from a nuts and bolts point of view, who really helped us organize

it at a professional level.

How long was your shooting schedule?

EC: It was October to November. Eight weeks, I guess.

That sounds quite long for an independent movie. How did you manage that?

JC: We didn't pay anybody anything. Well, we paid them the minimum. That's

the one thing I always say when people ask about this type of thing: it

makes more sense to find people who don't necessarily have the experience

doing what you want to do, but who you think are ready to do it and shoot

for longer, than it does trying to find some four thousand dollars a week

DP who you think is going to save you time and allow you to shoot for a

week less. It doesn't work like that. That was something Mark helped us

achieve and appreciate. That was the philosophy that he brought into the

movie and it was really helpful for us. The other thing we did, which I

think in retrospect was really smart, was we gave ourselves a very long

pre-production, too. Because we were dealing with very limited resources we

gave ourselves a really exhaustive pre-production and that ended up paying

off.

EC: Yeah, we storyboarded extensively, pretty much everything.

Did you work on that together?

JC: On

Blood Simple we did it together and then we worked with some

storyboard artists down in Texas.

How did you end up working with Barry Sonnenfeld?

EC: We met him through a mutual friend. He was in fact the person who

introduced us to Mark Silverman.

What had he done at this time?

EC: Odd things here and there. You know, 16 mm industrial type things. But

he hadn't shot a feature before. In fact I think he hadn't shot anything on

35 mm before.

JC: There was almost nobody on

Blood Simple, ourselves included obviously,

who had ever done a feature film before. Certainly not in the jobs that we

had hired them to do.

How did you work with Barry in terms of the look of the film? I thought

some of the scenes looked almost colour-coded. Blue when Marty is sitting

out on the back step looking at the incinerator or when the private eye is

breaking into John's house; red for Marty's bar and back office.

JC: Some of these things were conscious. But you may be reading more

calculation into it than actually happened. As most of these things are, it

was half by calculation and design and half just because that's what there

is. There was a conscious effort to make it crisp. Use hard sources and

make it cold.

EC: The thing you mention, looking at it again, I actually think we went

too far. We wouldn't have gone quite that far if we were doing it now. But

that probably came from talking to Barry about single light sources.

There's a blue bug zapper in that scene. There's a lot of neon in the bar.

How did you go about finding your key locations?

JC: Some of the actual locations in the movie were places that we were

aware of when we were writing the movie. Beyond that, I think we did it

just the way we normally do it. We hired a location manager who started

looking for places and showed us different options when we went down there.

I don't think it was any different in that respect from the other things

we've done subsequently.

EC: It's funny you ask about that. Looking for locations is always weird.

It's always surprising how specific you can get in your descriptions of

what you want and how you realize when you get shown things, how much

you've left out: what you really need. Everything superficially matches

what you're asking for but it's all basically kind of wrong. It's funny.

That never changes.

JC: So at the end of the day, you have to find these places yourself or go

out with whoever's looking.

EC: We would frequently choose things out of ignorance. The house that we

shot in, for instance, was so ridiculously small that when the AD came down

-

JC:-she told us we were crazy, that we'd never be able to get the crew in,

the lights and blah blah blah. It ended up actually working out okay but

she was right.

EC: We really made life difficult for ourselves out of ignorance.

I understand you had to vacate the bar at the weekend?

EC: That's right. It was empty during the week, then the swingers came in

at the weekend. They said, we got to keep it going at the weekend. So we

had to get out of there.

Let's talk about the casting. What made you think of M Emmet Walsh for the

part of the private eye? Did you know of him already?

JC: We hadn't met him. He was a Los Angeles guy. We knew him only from his

work, notably from a movie he did called

Straight Time in which he was

really good. It's an interesting movie in which Dustin Hoffman is a parolee

and M Emmet is his parole officer. M Emmet's character was sort of sleazy.

Actually it was a more interesting character than what we came up with in

Blood Simple inasmuch as it was more ambiguous. So, yeah, that was the

notable thing that we'd seen him in. We had our casting director send him a

script not in the expectation but in the hope that he'd be interested in it

and he was. It was a pleasant surprise that he was interested in doing it.

Where did you actually meet him for the first time?

EC: In Texas. We met him only when we were ready to shoot. He was the one

person we offered a part without an audition. All I remember is we didn't

know what the hell to call him! I mean, what the hell do you call him when

you meet him? 'M'?

Was he like the character he played?

JC: Emmet? No. He was a bit of a curmudgeon, certainly, but he didn't have

the sleaze that his character in the movie has.

EC: His sort of curmudgeonliness is not a cloud on the set. As a matter of

fact it's the opposite.

JC: Emmet's kind of crusty.

EC: He's kind of a coot.

JC: He's basically any noun or adjective that starts with a 'C'!

Did he ever give you a hard time?

EC: Yes, but in a half-kidding but only half-kidding kind of way. He never

tried to intimidate or make us feel insecure because of our lack of

experience although he had by far the most experience of anyone on the set.

What about the rest of the casting? How did that go?

EC: It was just the usual process of meeting actors. In our case, it was

here in New York, for the four main parts excluding Emmet. Actually, we met

Dan Hedaya, John Getz and Sam Mart fairly early on but hadn't met anyone we

were happy with for Fran's part until we met Fran. We met Holly Hunter and

liked her but that quickly became academic. She wasn't available because

she was doing a play in New York.

Copyright © 2002 by Various. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.