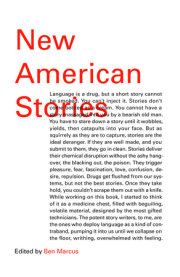

Part I

We Edit the World

1

Three Edits

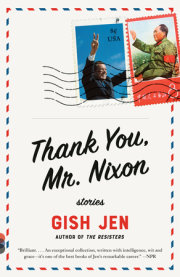

We edit the world. Witness this famous image from the 1989 Tiananmen protests in Beijing—the one of the single man who, the morning after the violent crackdown on the protesters began, simply stood in the road in front of a column of tanks on their way down Chang’an Avenue into Tiananmen Square, and refused to move. In the picture, he is holding two shopping bags; he looks as if he were simply going about his day when he happened upon the tanks and suddenly decided, I’ll block them. Both the BBC and CNN having been able to film the event, we know that when the lead tank tried to go around the man, he stepped into its path again—and then again and again, in a dance that in the videos seems almost cartoon-like. In truth, there was nothing playful about it. There was gunfire everywhere; these tanks were on a murderous mission. Still, when the lead tank finally stopped and, with all the rest of the column behind it, turned off its engine, the man climbed up onto its turret, called into a porthole, and spoke to a soldier. Then, later, when the tanks turned their engines back on and tried to move again, he leapt down and began blocking them once more—back and forth, back and forth—until he was finally pulled away. To this day, we do not know who pulled him. Nor do we know, sadly, what happened to this man. But all in all, it was a most heart-stopping confrontation. Indeed, it was one of the most riveting confrontations of the twentieth century, and his actions were without question transcendently brave. Were they, though, the actions of an interdependent self?

Many in the West would say no. Many would say that these actions represented the opposite of collectivism—that they were the actions of a true individualist, staying true to his avocado pit and standing up to an oppressive society. But that just goes to show how individualists filter the world. Though interdependent flexi-selves are more like members of a baseball team than they are art-for-art’s-sake artists, they are as capable of heroic action as any big pit self. Individualists have absolutely no monopoly on courage or initiative.

Strikingly interdependent was the moment when the man climbed up onto the tank and spoke to the soldier inside. That blurring of a boundary—in this case, between him and the tank—is, as we shall see, a hallmark of the flexi-self, and was interestingly the focus of some of the early coverage of the event. In fact, the first picture of the incident, circulated by Reuters and run for at least six hours in many newspapers worldwide, was a photo of the man up on the tank’s hull.

It was only later coverage that settled on the more individualistic picture—the iconic image of the man facing down the lead tank through which many of us could see what we wanted to see. For, perhaps a bit short and slight for the job, and somehow not wearing a holster or carrying a gun, the man in front of the tank nonetheless conjures up John Wayne. This is a man who fairly emanates the power of a single, courageous, authentic consciousness. He is standing up for freedom, as he must, we imagine, for there is something in him he cannot deny, something extraordinary; and in this he is like, say, Marshal Will Kane of the movie High Noon or lawyer Atticus Finch in the novel To Kill a Mockingbird, or any real genius or artist. Is it possible that he is just an ordinary man who wishes the soldiers would not fire on their fellow Chinese? And is it possible that he sees the soldiers as ordinary, too—as mere humans gone wrong, which is why he is knocking on their hatch? Well, no. We don’t see that.

That he may well be just such a man, though, is suggested by a study of two murderers done by researchers Michael Morris and Kaiping Peng. In comparing the U.S. coverage of two mass murders—one involving a Chinese physics student named Gang Lu and one involving an Irish American postal worker named Thomas McIlvane, both of which occurred in the autumn of 1991—they found significant differences between the leading English-language paper, The New York Times, and the leading Chinese-language paper, the World Journal. “American reporters attributed more to personal dispositions and Chinese reporters attributed more to situational factors,” they wrote. By this they meant that the English-language reporters ascribed Gang Lu’s actions to his avocado pit. “He had a very bad temper,” they said. He was a “darkly disturbed man who drove himself to success and destruction.” He had “psychosocial problems with being challenged.” And, “There was a sinister edge to Mr. Lu’s character well before the shootings.” In short, “whatever went wrong was internal.” In contrast, the Chinese-language reporters said nothing about Lu’s essential character, but rather blamed the things in his context that might have influenced him—his relationships and circumstances: He “did not get along with his advisor,” they wrote. He was in a “rivalry with the slain student.” He “was a victim of the ‘Top Students’ Education Policy.’ ” The incident “can be traced to the availability of guns.”

This pattern was the same for the Thomas McIlvane case. The English-language reporters emphasized McIlvane’s personal characteristics: He “was mentally unstable,” “had repeatedly threatened violence,” and “had a short fuse.” The Chinese-language reporters emphasized his circumstances: He “had recently been fired.” The “post office supervisor was his enemy.” He was inspired by the “example of a recent mass slaying in Texas.” And so on.

This conception of people as being shaped by their situations, as opposed to having sole control of their destinies, was echoed in a 2014 New Yorker article about a doctor stabbed to death by a patient named Li Mengnan in the northern Chinese city of Harbin. The doctor was not even treating Li; he was simply the first person Li saw when he walked in, frustrated and enraged by other events. And we should note that, horrendously as Li had in truth been treated, the doctor’s father did not feel the abuse excused Li’s actions. During the trial, the doctor’s father refused to accept Li’s apology: “Those words were not from the bottom of his heart,” he said. Li was eventually sentenced to life in prison. Later, though, when the New Yorker writer, Christopher Beam, asked the doctor’s father whom he blamed for his son’s death, the father answered, “I blame the health-care system . . . Li Mengnan was just a representative of this conflict. Incidents like this have happened many times. How could we just blame Li?”

Other cultures favor a situational model of responsibility as well. For example, in a comparative study of Israeli and American long-term unemployed, MIT Sloan School psychologist Ofer Sharone found that while Americans blamed themselves for their predicament, Israelis blamed the system. This did make the Israelis feel like commodities—that was the bad news. But the good news was that applying for jobs did not involve a referendum on their deepest selves. They were not particularly anxious about their self presentation, starting with their resumes. As one job hunter put it, “It’s not like the tablets on Mount Sinai. It’s the product specs.” Neither did they see the interview as about chemistry or like a date; and as for what ultimately happened, “These are idiotic situations that are determining your fate,” they said—frustrating, yes, but not a reason to think, as did so many Americans, “What’s wrong with me?”

Similarly, in a Peruvian school play about Little Red Riding Hood, the Big Bad Wolf was not simply big and bad. He was hungry, having fallen on hard times. And in a version I once saw in a Chinese elementary school, the Wolf was later remorseful—so much so that he regurgitated Little Red Riding Hood and her grandmother. The play ended with everyone—including the Wolf—holding hands and dancing in a circle.

Did the man in the Tiananmen tank picture similarly conceive of the soldiers as driven by circumstance rather than as bad guys? We cannot know, of course. But here’s the question: Given the way we Westerners edit the world, does it even occur to us that he might have?

For another example, take the self-portrait of a Chinese scholar on the next page. Exhibited in New York by the Asia Society, an organization dedicated to educating the world about Asia, this Self-Portrait in Red Landscape was painted by Xiang Shengmo in 1644, at the fall of the Ming Dynasty, a most traumatic time. The government having been overthrown by the foreign Manchus, many literati were simply distraught—among them, this painter, who expressed his deep grief by painting himself in black but his surroundings in red. This was a reference to the name of the Ming imperial family, which had meant “vermilion red,” and that this was a subversive act is clear from the fact that after its painting, the work was quickly hidden away, and not taken out again until the fall of the Manchus in 1911.

At the same time, we can see from all the inscriptions on the painting that the work as a whole is finally as much about community as it is about resistance: The central image is, after all, surrounded by the sympathetic writings of other Ming loyalists. Yet in 2013, when the Asia Society had a New York Times ad made out of the painting, the inscriptions were cropped out. As we can see in in an ad on the following page, the narrative of the work is presented as more individualistic than it actually is—a version, in fact, of the individual-versus-society narrative in the iconic Tiananmen tank photo. Once again we have the lone dissenter that dominates Western culture—the Thomas More who stands up to Henry VIII and his craven court in A Man for All Seasons, the Winston Smith who stands up to Big Brother in George Orwell’s 1984.

Can we blame an organization like the Asia Society for Westernizing the image? Their goal was to get people to visit their show, after all, and to do that they had to appeal to the readers of The New York Times—people likely to find the cropped image more compelling than the original. Of course, if these readers visited the show, they would then be confronted with images and narratives that challenged their worldview. But first they had to be gotten in the door—or so we might guess.

Here, in any case, is a third example of editing for which we have a clearer window into the decision-making. This example involves the writer Annie Dillard, who in 1974 published a riveting memoir called Pilgrim at Tinker Creek. Her book won the Pulitzer Prize and dazzled a whole generation, yours truly among them, thanks to passages like this:

At the time of Lewis and Clark, setting the prairies on fire was a well-known signal that meant, “Come down to the water.” It was an extravagant gesture, but we can’t do less. If the landscape reveals one certainty, it is that the extravagant gesture is the very stuff of creation. After the one extravagant gesture of creation in the first place, the universe has continued to deal exclusively in extravagances, flinging intricacies and colossi down aeons of emptiness, heaping profusions on profligacies with ever-fresh vigor. The whole show has been on fire from the word go. I come down to the water to cool my eyes. But everywhere I look I see fire; that which isn’t flint is tinder, and the whole world sparks and flames.

The writing is brilliant, ecstatic, visionary. Our hair stands on end. Sentence after sentence leaps from the page, sparking and flaming itself. And it does seem that in some ideal world their sheer quality should have been enough to make this a watershed book.

But Dillard was not at all sure that the world would take her—a “Virginia housewife named Annie,” as she called herself—seriously. And so Pilgrim styles itself as a kind of Walden with Dillard a kind of Thoreau even though, as Atlantic writer Diana Saverin points out, Dillard wasn’t “living alone in the wild. In fact, she wasn’t even living alone. She was residing in an ordinary house with her husband—her former college poetry professor.” What’s more, Dillard had written a thesis on Thoreau and knew perfectly well that stories of lone men in the wilderness often involved some hooey. “In Wildness is the preservation of the World,” Thoreau wrote in his 1862 essay “Walking,” for example. Yet as Saverin asks,

[W]hat was the “wildness” Thoreau was describing? Critics have pointed out that Thoreau’s cabin, on land owned by his friend Ralph Waldo Emerson, was within easy walking distance of Concord. There were rumors that he’d had his mother do his laundry the whole time.

And indeed, his time there included many dinners with friends and family, and even a rally at the cabin for the Concord Female Anti-Slavery Society. So thoroughly networked was he that, though he might well have liked to have spent more time in jail when he was arrested for not paying his poll tax, his relatives found out about his arrest so quickly, and so immediately paid what needed to be paid, that he could not escape being released.

Still, knowing what American audiences wanted, Dillard went out of her way to emphasize her aloneness. In the first chapter, she compares her home to “an anchorite’s hermitage,” and later, she writes, “I range wild-eyed, flying over fields and plundering the woods, no longer quite fit for company.” The only human interaction she has in the book is with a man who gives her a Styrofoam cup of coffee on a solitary drive home. The husband with whom she lives, the friends with whom she lunches, and the teammates with whom she plays softball are all conspicuously missing.

Her omissions were so extreme as to be funny to those in the know. As Dillard wrote in her journal, her friends “said, laughing, that they got the sense I was living in this incredible wilderness.” And certainly back when, as a grad student, I first read Pilgrim, that is the sense I got, too. In truth, though, the “incredible wilderness” was a stretch of woods near Hollins College, in a suburb, as Dillard came to admit. She reports:

[B]efore publishing Pilgrim [Dillard] hadn’t realized how wild she’d made the valley seem. “I didn’t say, ‘I walked by the suburban brick houses’ . . . Why would I say that to the reader? But when I saw that reviewers were acting like it was the wilderness, I said, ‘Oh, shit.’ So the first thing I wrote after [that was an essay in which I pointed out,] ‘This is, mind you, suburbia.’ Because I hadn’t meant to deceive anybody. I just put in what was interesting.”

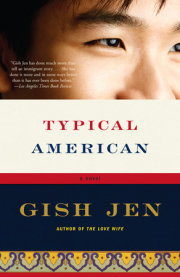

Copyright © 2017 by Gish Jen. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.