CHAPTER 1

Create Dangerously: The Immigrant Artist at Work

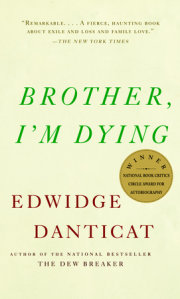

On November 12, 1964, in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, a huge crowd gathered to witness an execution. The president of Haiti at that time was the dictator François “Papa Doc” Duvalier, who was seven years into what would be a fifteen-year term. On the day of the execution, he decreed that government offices be closed so that hundreds of state employees could be in the crowd. Schools were shut down and principals ordered to bring their students. Hundreds of people from outside the capital were bused in to watch.

Th e two men to be executed were Marcel Numa and Louis Drouin. Marcel Numa was a tall, dark-skinned twenty-one-year-old. He was from a family of coffee planters in a beautiful southern Haitian town called Jérémie, which is often dubbed the “city of poets.” Numa had studied engineering at the Bronx Merchant Academy in New York and had worked for an American shipping company.

Louis Drouin, nicknamed Milou, was a thirty-one-year-old light-skinned man who was also from Jérémie. He had served in the U.S. army—at Fort Knox, and then at Fort Dix in New Jersey—and had studied finance before working for French, Swiss, and American banks in New York. Marcel Numa and Louis Drouin had been childhood friends in Jérémie.

Th e men had remained friends when they’d both moved to New York in the 1950s, after François Duvalier came to power. There they had joined a group called Jeune Haiti, or Young Haiti, and were two of thirteen Haitians who left the United States for Haiti in 1964 to engage in a guerrilla war that they hoped would eventually topple the Duvalier dictatorship.

The men of Jeune Haiti spent three months fighting in the hills and mountains of southern Haiti and eventually most of them died in battle. Marcel Numa was captured by members of Duvalier’s army while he was shopping for food in an open market, dressed as a peasant. Louis Drouin was wounded in battle and asked his friends to leave him behind in the woods.

“According to our principles I should have committed suicide in that situation,” Drouin reportedly declared in a final statement at his secret military trial. “Chandler and Guerdès [two other Jeune Haiti members] were wounded . . . the first one asked . . . his best friend to finish him off; the second committed suicide after destroying a case of ammunition and all the documents. That did not affect me. I reacted only after the disappearance of Marcel Numa, who had been sent to look for food and for some means of escape by sea. We were very close and our parents were friends.”

After months of attempting to capture the men of Jeune Haiti and after imprisoning and murdering hundreds of their relatives, Papa Doc Duvalier wanted to make a spectacle of Numa and Drouin’s deaths.

So on November 12, 1964, two pine poles are erected outside the national cemetery. A captive audience is gathered. Radio, print, and television journalists are summoned. Numa and Drouin are dressed in what on old black-and-white film seems to be the clothes in which they’d been captured— khakis for Drouin and a modest white shirt and denim-looking pants for Numa. They are both marched from the edge of the crowd toward the poles. Their hands are tied behind their backs by two of Duvalier’s private henchmen, Tonton Macoutes in dark glasses and civilian dress. The Tonton Macoutes then tie the ropes around the men’s biceps to bind them to the poles and keep them upright.

Numa, the taller and thinner of the two, stands erect, in perfect profile, barely leaning against the square piece of wood behind him. Drouin, who wears brow-line eyeglasses, looks down into the film camera that is taping his final moments. Drouin looks as though he is fighting back tears as he stands there, strapped to the pole, slightly slanted. Drouin’s arms are shorter than Numa’s and the rope appears looser on Drouin. While Numa looks straight ahead, Drouin pushes his head back now and then to rest it on the pole.

Time is slightly compressed on the copy of the film I have and in some places the images skip. There is no sound. A large crowd stretches out far beyond the cement wall behind the bound Numa and Drouin. To the side is a balcony filled with schoolchildren. Some time elapses, it seems, as the schoolchildren and others mill around. The soldiers shift their guns from one hand to the other. Some audience members shield their faces from the sun by raising their hands to their foreheads. Some sit idly on a low stone wall.

A young white priest in a long robe walks out of the crowd with a prayer book in his hands. It seems that he is the person everyone has been waiting for. The priest says a few words to Drouin, who slides his body upward in a defiant pose. Drouin motions with his head toward his friend. The priest spends a little more time with Numa, who bobs his head as the priest speaks. If this is Numa’s extreme unction, it is an abridged version.

The priest then returns to Drouin and is joined there by a stout Macoute in plain clothes and by two uniformed policemen, who lean in to listen to what the priest is saying to Drouin. It is possible that they are all offering Drouin some type of eye or face cover that he’s refusing. Drouin shakes his head as if to say, let’s get it over with. No blinders or hoods are placed on either man.

The firing squad, seven helmeted men in khaki military uniforms, stretch out their hands on either side of their bodies. They touch each other’s shoulders to position and space themselves. The police and army move the crowd back, perhaps to keep them from being hit by ricocheted bullets. The members of the firing squad pick up their Springfield rifles, load their ammunition, and then place their weapons on their shoulders. Off screen someone probably shouts, “Fire!” and they do. Numa and Drouin’s heads slump sideways at the same time, showing that the shots have hit home.

When the men’s bodies slide down the poles, Numa’s arms end up slightly above his shoulders and Drouin’s below his. Their heads return to an upright position above their kneeling bodies, until a soldier in camouflage walks over and delivers the final coup de grace, after which their heads slump forward and their bodies slide further toward the bottom of the pole. Blood spills out of Numa’s mouth. Drouin’s glasses fall to the ground, pieces of blood and brain matter clouding the cracked lenses.

The next day,

Le Matin, one of the country’s national newspapers, described the stunned-looking crowd as “feverish, communicating in a mutual patriotic exaltation to curse adventurism and brigandage.”

“The government pamphlets circulating in Port-au-Prince last week left little to the imagination,” reported the November 27, 1964, edition of the American newsweekly

Time. “ ‘Dr. François Duvalier will fulfill his sacrosanct mission. He has crushed and will always crush the attempts of the opposition. Think well, renegades. Here is the fate awaiting you and your kind.’ ”

All artists, writers among them, have several stories—one might call them creation myths—that haunt and obsess them. This is one of mine. I don’t even remember when I first heard about it. I feel as though I have always known it, having filled in the curiosity-driven details through photographs, newspaper and magazine articles, books, and films as I have gotten older.

Like many a creation myth, aside from its heartrending clash of life and death, homeland and exile, the execution of Marcel Numa and Louis Drouin involves a disobeyed directive from a higher authority and a brutal punishment as a result. If we think back to the biggest creation myth of all, the world’s very first people, Adam and Eve, disobeyed the superior being that fashioned them out of chaos, defying God’s order not to eat what must have been the world’s most desirable apple. Adam and Eve were then banished from Eden, resulting in everything from our having to punch a clock to spending many long, painful hours giving birth.

The order given to Adam and Eve was not to eat the apple. Their ultimate punishment was banishment, exile from paradise. We, the storytellers of the world, ought to be more grateful than most that banishment, rather than execution, was chosen for Adam and Eve, for had they been executed, there would never have been another story told, no stories to pass on.

In his play

Caligula, Albert Camus, from whom I borrow part of the title of this essay, has Caligula, the third Roman emperor, declare that it doesn’t matter whether one is exiled or executed, but it is much more important that Caligula has the power to choose. Even before they were executed, Marcel Numa and Louis Drouin had already been exiled. As young men, they had fled Haiti with their parents when Papa Doc Duvalier had come to power in 1957 and had immediately targeted for arrest all his detractors and resistors in the city of poets and elsewhere.

Marcel Numa and Louis Drouin had made new lives for themselves, becoming productive young immigrants in the United States. In addition to his army and finance experience, Louis Drouin was said to have been a good writer and the communications director of Jeune Haiti. In the United States, he contributed to a Haitian political journal called

Lambi. Marcel Numa was from a family of writers. One of his male relatives, Nono Numa, had adapted the seventeenth-century French playwright Pierre Corneille’s

Le Cid, placing it in a Haitian setting. Many of the young men Numa and Drouin joined with to form Jeune Haiti had had fathers killed by Papa Doc Duvalier, and had returned, Le Cid and Hamlet-like, to revenge them.

Like most creation myths, this one too exists beyond the scope of my own life, yet it still feels present, even urgent. Marcel Numa and Louis Drouin were patriots who died so that other Haitians could live. They were also immigrants, like me. Yet, they had abandoned comfortable lives in the United States and sacrificed themselves for the homeland. One of the first things the despot Duvalier tried to take away from them was the mythic element of their stories. In the propaganda preceding their execution, he labeled them not Haitian, but foreign rebels, good-for-nothing

blans.

Copyright © 2011 by Edwidge Danticat. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.